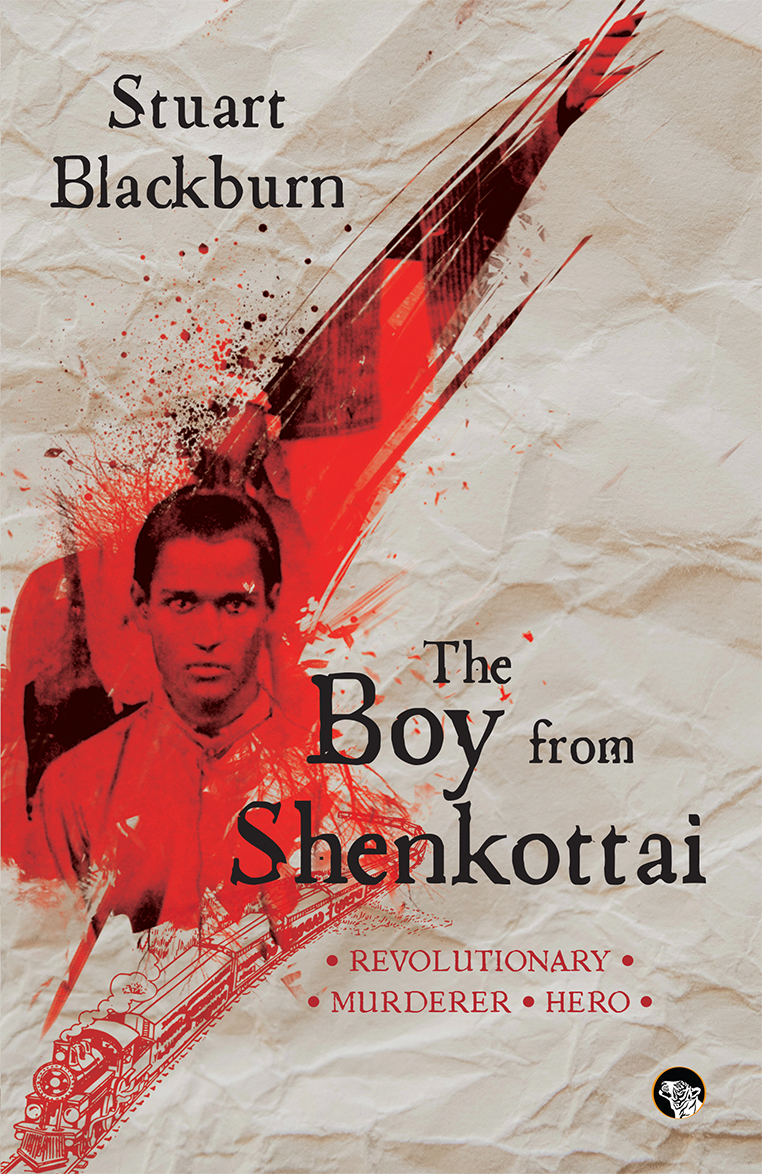

The Madras Presidency, 1911. It is 10:35 a.m., the appointed hour. A boy barely into manhood, a British officer for the Crown, and a loaded pistol will create a moment in history, the echoes of which are still faintly heard today.

Vanchinathan, a young boy from a poor Tamil family living in Shenkottai, at the foothills of the western ghats, defies his family and goes far away to attend college. Carried away in the rising tide of anger against colonial rule, he finds himself drawn to one of the militant traditionalist groups opposed to the British Raj. He is recruited, trained to be an assassin and tasked with a secret mission: he must kill Robert Ashe, a British officer who has earned the ire of Vanchi’s mentors by suppressing a riot and jailing its leader. Buffeted by self-doubt and ideological misgivings, Vanchi finds himself on a knife-edge. As Ashe’s luxury train waits at an isolated station, will Vanchi raise his gun and shoot?

Drawing upon a true story, Stuart Blackburn weaves together history, legend and narratives from South India’s colonial past to deliver a gripping yet nuanced novel.

The following is an excerpt from the book ‘The Boy from Shenkottai’ written by Stuart Blackburn and published by Speaking Tiger Books.

When Ponammal heard the moaning, it was pitch black on a muggy night. Rolling over onto her stomach, she propped herself up on her forearms and looked out through the kitchen doorway. She could just make out the hammock hanging from the beams in the front room, where her daughter slept. She saw that it was motionless and relaxed.

Vanni was not a healthy child, everyone could see that. She ran around, played and laughed like a normal little girl, but she often had a high fever and the spots remained on her skin like a permanent stain. Ponammal went to the goddess temple every Tuesday to pray for her, and Thatha supplied her with special potions. She also hung another wooden cradle on the tree, telling herself that Vanni would like to have a brother or sister. Deep down, she wondered if she were hoping for a replacement.

She turned over and was half-asleep when she heard the moaning again. Not at all child-like. It was coming from her husband lying in another corner of the kitchen, a position he had taken up for the past several months. No explanation had been given and none asked for.

‘Hey,’ she whispered. ‘Quiet.’

But the low moan continued and became a growl.

‘What’s the matter?’

No response, so she crawled over and shook him hard on the shoulder.

Vanchi screamed.

‘It was the head,’ he told her after the others in the front room had been assured that nothing was the matter.

‘What?’

‘I saw his head. The one I…’ He stopped and stared at the wall. ‘What day is it?’

‘Can’t see in the dark.’

Vanchi lit the kerosene lamp and held it close to the calendar hanging on the wall. It was a thick pad of small square sheets, one for each of the days of the Tamil year. He didn’t read the astrological information and ritual instructions, or even notice the English date of 30 January. It was enough to know that it was the full-moon day. And he wasn’t surprised.

Almost a year had passed since he had taken the blood oath. He and Shankara continued to distribute leaflets sent from Pondicherry, though Vanchi’s excuses were beginning to wear thin at home and at work. He had also recited the oath once a month, as Nilakanta had ordered, but he couldn’t bear to do it while looking at the blood-stained paper hidden in the banyan tree. Instead, he had memorized the words and repeated them on each full-moon day, on his walk to the bathing pool in the morning. That way it all stayed inside his head, where it was safe.

‘Here, take this,’ Thatha said in the morning and handed him a concoction of ground ginger root and senna leaves. ‘You’re not sleeping well, she says.’

They were sitting on the veranda after breakfast. The women were eating inside with Vanni, their laughter audible. Men and boys were moving in the narrow Brahmin street, coming and going from their bath and other morning business. Towels were slung over their shoulders, wrapped around their waists or turban-like on their heads. The early morning sun had cleared the tree tops, and steam rose from the ground with a hiss.

Vanchi drank the concoction and looked at the kolam on the ground in front of the veranda. It was a complex design, made only on that full-moon day. Large circles connected by broad stripes formed a ring around a grid pattern in the centre.

‘Afternoon shift today?’ Thatha asked.

‘Yes.’

‘Why not come with me then? I’m going towards Thenmala, to get some honey.’

‘Ah, I can’t.’

Thatha raised a bushy eyebrow. ‘Then come to temple with me,’ he said.

Thatha led the way down the street. The gauze-like mist had burned off, letting the sun warm every bone of Thatha’s thin body. He carried a small, round brass pot of cooked rice mixed with spices and milk.

Together, they ducked inside the dank space, just big enough for them to stand up in and hold another two or three people. The air smelled of coconut oil. In front of them, Shiva sat cross-legged on a raised plinth, his dark body festooned with a garland of bright marigolds. Red hibiscus flowers, with phallic-like protruding stigma, lay scattered on the ground.

Vanchi watched as Thatha moved forward and placed his pot on the edge of the plinth, close to the god’s feet. Stepping back, but still facing the god, Thatha stood beside Vanchi. They chanted verses that celebrated the marriage of Shiva and Parvati and blessed their sons, Murugan and Ganesha. After they prayed silently for a few minutes, Thatha poured the rice mixture over the god and both men withdrew.

‘You know, it’s not just Shiva’s marriage we honoured in there,’ Thatha said as they walked back to the house. ‘It’s every marriage, all husbands and wives.’

Vanchi looked straight ahead, avoiding Thatha’s eyes and trying to ignore his words.

As soon as they reached the house, Thatha buckled on his leather belt and picked up two jute bags. ‘Right, I’m off,’ he said. ‘You should go to temple more often. It’s good for you.’

Vanchi watched his grandfather walk away. He’s right, he thought. I do feel better when I’m chanting and praying. When it’s all under control. With lines that mark beginnings and endings.

Vanchi waited until Thatha had disappeared into the jungle behind the temple before he set out for the bathing pool. Fifteen minutes later, he had passed through the market and turned off the main road onto the path through the paddy fields. Once inside the forest, he recited the oath. Neither aloud nor in a whisper, this time his voice found a rhythm in the phrases, a regular pattern of rising and falling tones, which carried him to the end: ‘When we drink kumkum, it is the blood of white men.’ The oath had become a chant.