Between May 2015-May 2016, the Iraqi writer Haifa Zangana held two 12-hour workshops, in Ramallah, with 10 Palestinian women political prisoners, recently liberated from Israeli prisons where they had been held captive for upto 10 or 12 years. Zangana herself had been arrested by Saddam Hussein in the 1970s, along with several other Iraqi communists, who were imprisoned and tortured in the now infamous Abu Ghraib prison. Dreaming of Baghdad , her powerful memoir, written in exile, is not only an account of her incarceration but an act of retrieval, testimony to the redemptive potential of writing.

Haifa Zangana’s writing workshops with the Palestinian women encouraged them to recall their experience in words, using a form of their choice, to record the humiliation and indignity they were subjected to by the Israeli government, but also to hope for catharsis through writing and remembering. They wrote, says Haifa, “to defy the oppressive system designed to silence them”.

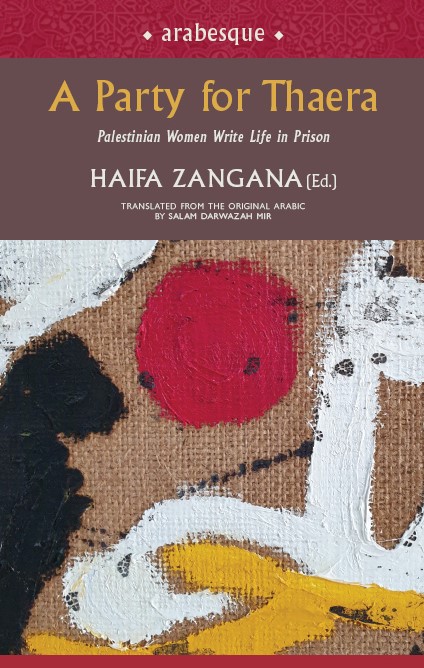

A Party for Thaera brings together their diverse offering — as short story, memoir, diary, letters, a poem or song, even a dream — in poignant and vivid detail and is, at once, an act of courage as well as of resistance.

In this conversation with writer and publisher Ritu Menon, Zangana talks about the book and more.

Ritu Menon (RM): How did you identify the participants for your workshop?

Haifa Zangana (HZ): Identifying the participants was a joint effort between the Tamer Institute for Community Education, the Society of Women Imprisoned for Seeking Freedom (Maseera) and myself. We agreed on two basic conditions. First, the workshop would be open to any woman who was a former political prisoner; second, participants had to want to write. Priority would be given to women who had previously tried their hand at writing, of whatever kind—letters, journals, short stories, poetry, and so on.

RM: All the women were liberated from captivity after several years in prison — how challenging was it for them to recollect and recount their experience?

HZ: It varied. On the one hand, writing exercises focusing on describing sounds, odours, colours, senses, and details of places and people, helped to trigger remembering certain events and moments which had been shelved in a dark corner, not to be seen or recognised. On the other hand, two of the participants had kept some kind of a diary and letters. Reading aloud some excerpts of that helped as well. In addition to that, it just happened that three of the participants had shared the same cell in prison, which contributed to making the process of recollecting a group act rather than an individual one, and was extremely useful in documenting dates.

RM: This act of remembering — did they experience it as cathartic or traumatic?

HZ: It was cathartic to a certain extent. They were keen to attend and to write their own stories instead of having others write for them. Having said that, there were moments of crying when remembering how loved ones, especially children or mothers, were missed, but there were also moments of laughter. Being within a group helped remove some of the trauma and ease the deep feeling of pain and sadness towards certain traumatic events, enabling them to see their experience through a different lens.

RM: In her Introduction, Ferial Ghazoul speaks of “the ailment of oppression and occupation; the remedy in acts of resistance and transcendence; and writing as the means of healing”. Can you comment on this observation, based on your interactions with the writers?

HZ: The timing and the harmony among the participants, despite their different political backgrounds, played a major role in turning their writings into another tool of their continued resistance against occupation for freedom, justice and equality. A group talking, within the workshop, followed by writing and vice versa, also helped ease the way to adapt writing as a way of self-expression within an overall public resistance.

RM: The group included some who are writers — Rose Shomali, Nour Bourhan — and others who had never written before. How did this difference play out in the workshops?

HZ: To start with, I was worried about that but it didn’t take me long to realise that there was no need whatsoever to worry. The participants knew each other and, in some cases, worked together. Rose, though a well-known poet and writer, and of a different generation, has been very modest and her presence, together with Bourhan, enriched the workshop. The atmosphere was amazing — of respect, understanding, and acknowledging the importance of writing as a powerful tool of resistance.

RM: May Ghosain was sentenced to Life +12 years in prison, during which she drew on the walls of every cell she occupied — this would be what is called a “distinctive text”. Can you tell us more about this extraordinary woman?

HZ: She is definitely an extraordinary woman. She is so passionate about art to the extent she is running a centre for teaching art to children in her village. In order to attend the workshop, she had to travel for a long time and had to face multiple Israeli check points. Yet she didn’t miss a day and she used to write her “homework” while waiting for the often-delayed bus to and from Ramallah. The wonderful thing is that her relationship with writing continued after the workshop and publishing the book. In July this year, we organised the launch, via Zoom, of her own book entitled Mosaic Stone as well as Nadia’s book Burnt to Light.

RM: In “Separation” Iman Ghazzawi writes that she would wait till everyone else was asleep, then take out the photos of her children and talk to them. One day, the jailor confiscated the photos — would you say this was a deliberate theft of memory by the jailor?

HZ: Absolutely. It was an act to deprive Iman, being a mother, of the presence of her children as embodied in the photos, thus isolating her and preventing her from recalling happy times when they were together. A systematic act which is more cruel and painful than physical torture that symbolises as well the theft of Palestine and the daily process of trying to erase its people’s memory by the settlers/occupiers.

RM: What is palpable in all the accounts is the weight of time — in prison, in exile, in waiting. Was there any discussion on this in the workshops?

HZ: Although we did not spend enough time discussing it, it was conveyed clearly in the participants’ narratives. Time became waiting. An instrument of control and psychological torture by the guards. Waiting for visits, to see family members, waiting for trials, waiting to be sentenced, to be able to sleep, or receive a letter. There is also the waiting related to any political change taking place outside the walls of the prison. In fact, the weight of time overshadowed every minute of their existence whether in prison or outside it, and in case of Rose, in exile.