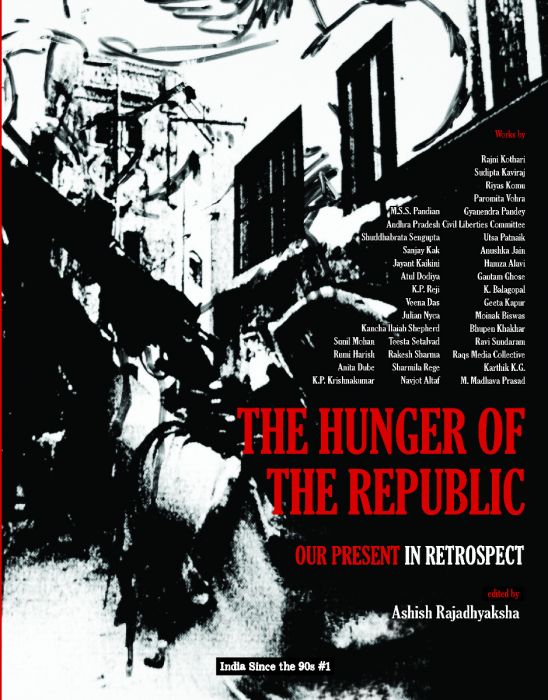

India Since the 90s (general editor: Ashish Rajadhyaksha) is a series of six titles exploring India’s recent history to produce a retrospective account of how our present got shaped.

Edited by Rajadhyaksha, The Hunger of the Republic: Our Present in Retrospect is the first of the series. A return to the last three decades, and to the mutations caused by globalization to concepts such as democracy, welfare and justice, indeed the very idea of the people as citizen-subjects, produce a new staging ground for the apparently unprecedented nature of the contemporary moment. Key essays on politics, economics, cultural studies, and aesthetics appear alongside works of art, documentary film, photography, maps, letters and legal documents.

The following are excerpts from Ravi Sundaram’s piece titled ‘Beyond the Nationalist Panopticon: The Experience of Cyberpublics in India (1996)’.

INDIA, CYBERSPACE AND THE PUBLICS

If one were to adopt a certain diffusionary model of the spread of cyberpractices in India, we would have to consider the following:

a) The simple fact of India being a peripheral society in the capitalist world-economy: with one of the lowest saturation rate of telephones in the world; only a small minority of the population has electricity.

b) India has no tradition of cyberpunk; in fact there is no indigenous science fiction tradition. Most existing cultural communities have remained ambivalent about technology. Historically, representations of science and technology have been state-sponsored and social-realist in form.

Despite this, a significant number of people are linked to electronic networks in India, and the number is fast growing. For a Third-World country with inequalities like India, this is quite remarkable. ‘Cyberspace’ has emerged as a significant term in public discourse in India, becoming the focal point of much coverage and speculation in the media. Behind all of this is the growing community of users. Till date anonymous, and lacking the ‘heroic’ qualities of the old nationalist scientist, the contemporary user lacks any visible representation of his or her agency.

I have tried to map the ‘user’ into three, overlapping cyberpublics. ‘Public’ is used here very loosely, indicating a cybercommunity in the making, where mutual rituals of initiation and excursion are only now being invented. The three cyberpublics are those of the nationalist state, the transnational elite, and that of the space between the market and the state occupied by various bulletin boards, and social movement networks. While the boundaries of all the three publics are fuzzy, they are also uneven in internal differentiation and modes of address. Cyberpublics are a relatively new phenomenon in India. What is attempted here is a very preliminary examination of these communities-in-formation, by mapping certain practices of the nationalist organization of space, and its consequences for agency and movement.

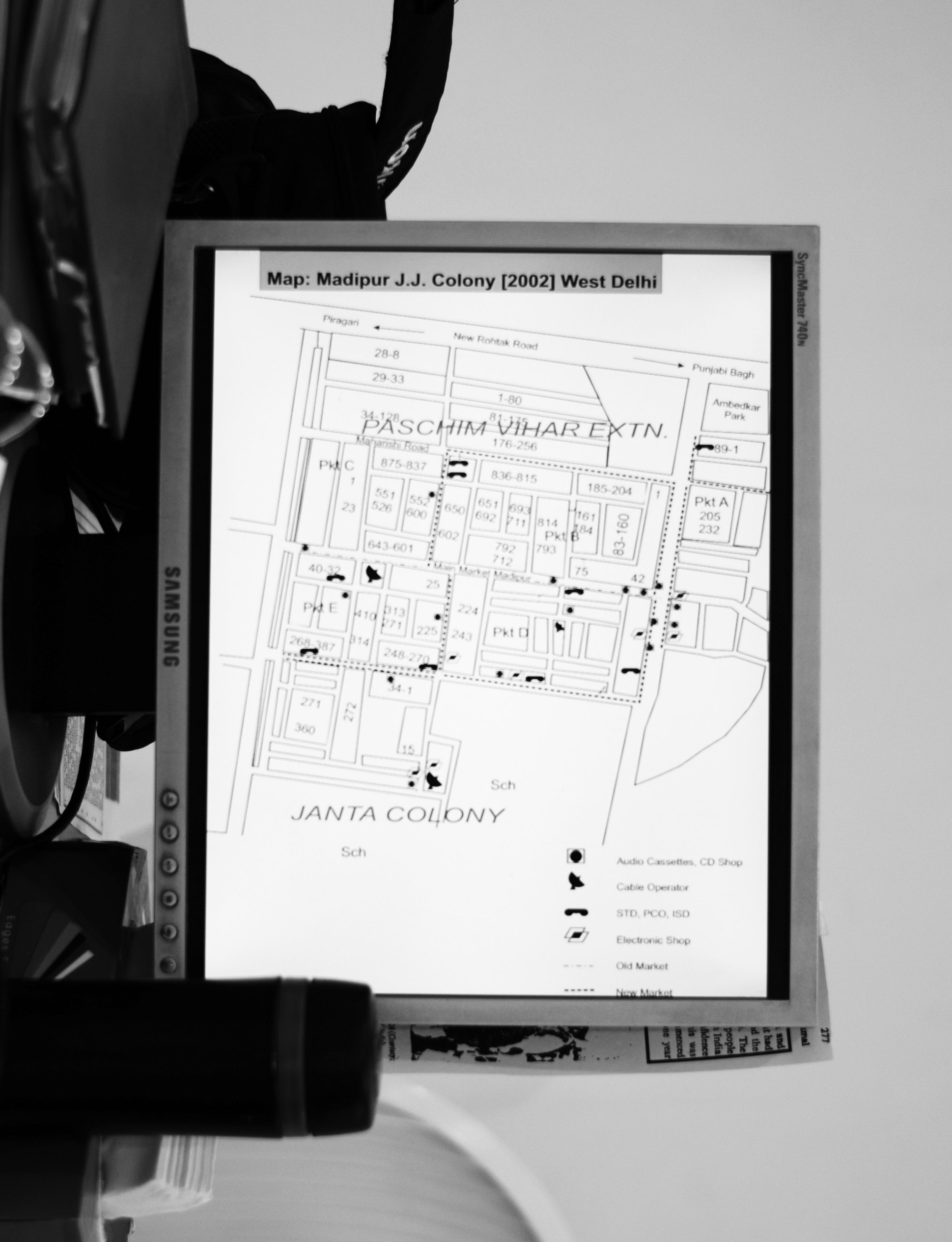

Nationalist policies employed a certain social cartography which attempted to organize space, representation and identity. Maps generated ‘borders’, which in turn sought to institutionalize identity, frame representations of citizenship, and mediate the relationship with the west and modernity.[1] Mapping activities which were backed by the state’s monopoly of legitimate violence were also implicated in a particular version of post-war modernism. The metaphor of the map is also useful to highlight different strategies which emerged in the post-national period, which sought to re-organize space by dislocating it from territory, and posit new forms of identity.

[…]

THE TROPE OF JOURNEY

In many ways, cybertime in a peripheral society like India can be seen as radically revising the idea of the journey. Travelling was the basis of knowledge about others in pre-colonial civilizations – including that in South Asia. The great temporal community of the traveller was largely oral, and based on sustained interaction with other communities. In the world of the Dar-ul-Islam, which dominated the pre-modern world, travelling was the duty of every Muslim, either on the Haj to Mecca at least once a lifetime, or to learn about other Islamicate states in the realm. These were not the journeys of the Creole intelligentsia in the period of print-capitalism – a premium was placed on oral interaction with fellow Muslims. This was a journey without frontiers – the traveller was constrained only by physical limitations. Time operated through different registers – there was no temporal compulsion on the travellers’ return: travellers came back after many years.

The nationalist journey was the great invention of Gandhi. The Gandhian journey began with a paradox: it used the railway network – one Gandhi had denounced as having destroyed the pre-colonial narratives and experiences of the Journey.

The railways disrupted the Indian body politic, which Gandhi saw as a huge body digesting and assimilating different cultural elements. He then showed how the two technologies, reflected in pilgrimage on foot by rail, represented memory and erasure respectively. The pilgrim’s progress was an act of faith. The arduous act of pilgrimage to different corners of India gave the pilgrim a sense of both neighbourhood and nationhood, helping him to internalize both similarities and differences.

The mechanical negotiation or ‘ingestion’ of territory through rail travel erased the sanctity of places and turned them into physical spaces.[2]

In fact, Gandhi’s privileged journey was foot-travel. The practice of walking meant a different language of interaction, of knowledge. It was only through walking that humans came into interaction with different cultures and peoples – which abstract motions of locomotion could not provide. The allusion to the pre-modern traveller/pilgrim could not be more direct.

However, Gandhi did use the railway extensively during anti-colonial agitation. To counter his own ambivalence vis-à-vis the industrial capitalism, Gandhi carved out an area within the train – the third-class compartment – a simulated space where people ‘entered’ the train with the humility of the pre-modern pilgrim. Gandhi’s innovation was to transform the Journey as a vehicle to politically remap the nation. This was also a journey-as-dialogue, with conventions of public interaction, anti-colonial agitation and spectacle. In a typically Gandhian way, the railway grid (colonialism’s most ambitious disciplinary structure) was subjected to a series of inversions. This was despite Gandhi’s own ambivalence vis-à-vis modern technology.[3] The Gandhian journey was also a public journey, with the attendant modes of representation constructing an imaginary community of nationalism.[4] Colonialism introduced the political technology of the modern state, with the attendant modes of political control. Frontiers became Borders, and modern citizens in post-colonial India were subject to new mechanisms of political identity. The Journey was governed by clear notions of sovereignty; passports became a necessary precondition for travel abroad. Indian nationalism was always suffused with cartographic anxiety[5] – a phenomenon made worse by the partition of the subcontinent and the wars with Pakistan and China. State-sponsored import-substitution industrialization drives regulated the import of foreign consumer items, and so what obtained was a kind of physical separation of the ‘everyday’ from the west for about twenty years. Filiality to the border became a marker for citizenship with state campaigns against smuggling intensifying during the authoritarian period of the 1970s. The state’s claim was that of a monopoly over identity formation, citizenship and national representation.

From the 1950s onwards, popular cinema generated a series of films where a large part of the narrative unfolded in the west with Indian characters. While the melodramatic structure of the films was based on a final resolution at the point of origin (India), what is interesting is the visual mapping of the ‘west’ simulating a virtual tour of that geographic space for millions who had been denied that chance. This substitute travelogue, though mediated through the foundational myth of nationalism, nevertheless speculated on the space ‘outside’ the border.[6]

James Clifford has written that ‘a journey makes sense as a “coming to consciousness” its story hardens around your identity. (Tell us about your trip)’.[7] Journeys into virtual space allowed for the de-stabilizing of this ‘hardening’ of identity – it has generated new ‘boundary stories’ about virtual cultures in India. For one, the idea of the Border, so central to state-nationalism is transcended. The new experience of cyberspace that allows the citizen to ‘arrive without having set out’ disrupts the old realist confines of the Journey: for the first time in the history of the visual regimes set in motion by the west, the Third World is allowed entry into hitherto prohibited spaces.

This journey is nevertheless embedded in new networks of power: the ethnoscapes of post-nationalism:[8] a de-territorialization of the old nationalist space, confined by the Border and a transnational territorialization where India was being invented in virtual space by sections of non-resident Indians. The state actively pushed a new category of identity in cultural/ political discourse – the figure of the diasporic citizen, also known as the NRI or non-resident Indian.

With the NRI, the border was extended to those spaces outside national sovereignty where the diaspora lived. In the old nationalist imaginary, people left the home of the nation only to return – sometime. The discourse of the 1980s restated the idea of the emigrant’s ‘return’ – only to make it temporally indeterminate. The NRI was now part of a ‘national’ community – yet emancipated from the ‘place’ of the nation. As the NRI had a natural affinity for Home, any capital he/she brought in to the country would be motivated by patriotic feelings in contrast to say, multinational capital. In the 1990s however, as national development receded, the NRI began to play a prominent role in new virtual spaces. The idea of the Return now became less relevant – it was achieved in pure space.

1. Sankaran Krishna, ‘Cartographic Anxiety: Mapping the Body Politic in India’, Alternatives, 4, 1994.

2. Nandy, The Savage Freud, pp. 181–82.

3. This was in contrast with Marx’s optimistic view. Marx tended to see the role of the railway in India very much as Baudelaire saw Baron Von Haussmann’s reconstruction of Paris in the mid-nineteenth century – the process of destruction and opening up of imaginative modes of social action.

4. A comparative journey, though more focused in time and space, is the Long March undertaken by the Chinese Red Army in 1934–35.

5. Krishna, ‘Cartographic Anxiety’.

6. The exhibition mode had a limited presence in India. The great nationalist exhibition was Expo 72 in New Delhi in 1972. In a space specially built for the purpose, various Indian states and, more important, foreign (mainly western) countries put up halls for visitors. This was the Third World and Nehruvian version of the Crystal Palace, and was a huge success at the time. Since then exhibitions have tended to be more focused, concentrating on commercial and business interests rather than recreate the spectacle-like quality of Expo 72.

7. James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988, p. 167.

8. Arjun Appadurai, ‘Patriotism and Its Futures’, Public Culture, 5, 1993, pp. 411–29.