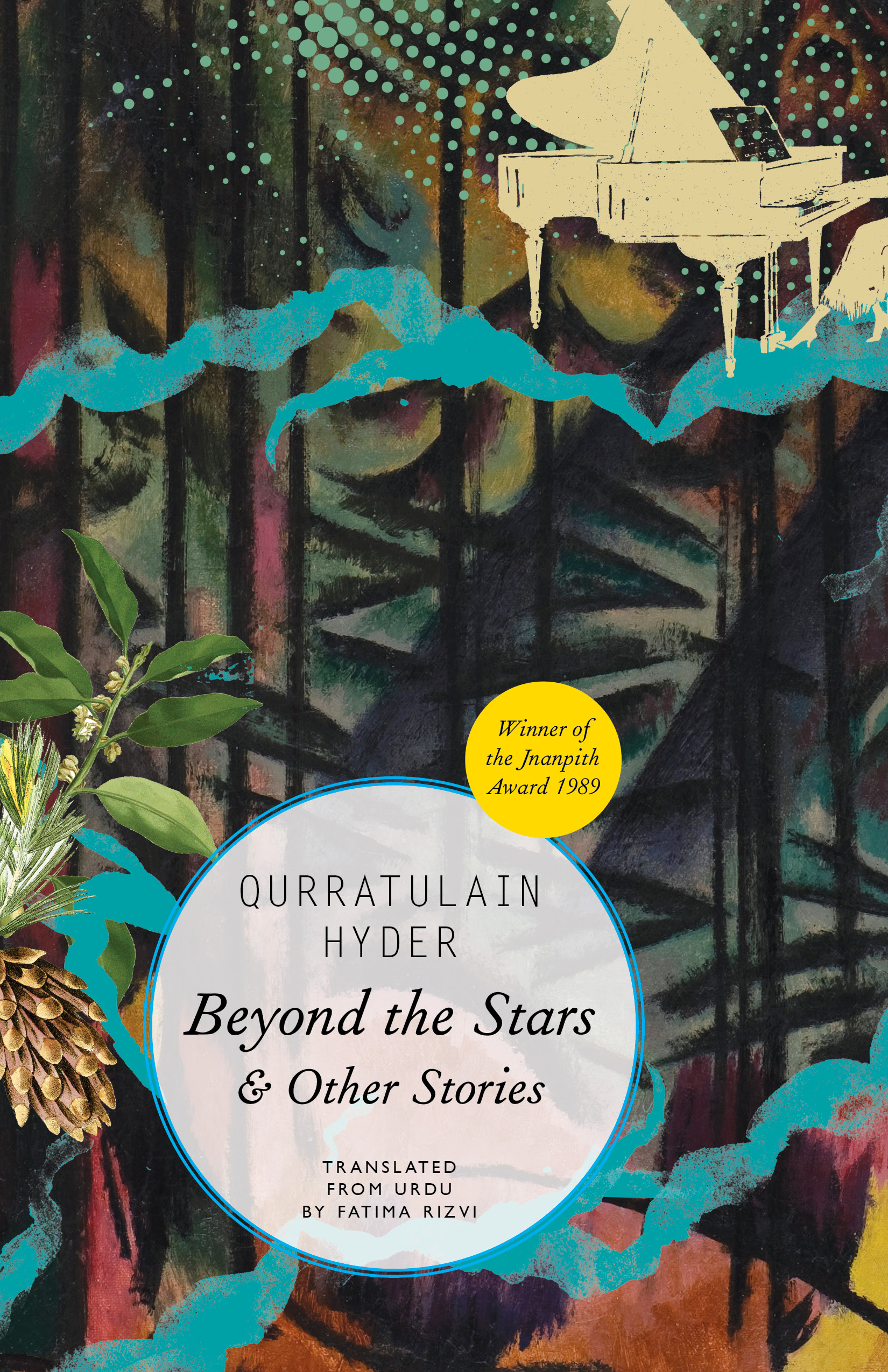

Written while she was still in her late teens, Beyond the Stars (Sitaron se Aage) was Qurratulain Hyder’s earliest published anthology of stories. Translated by Fatima Rizvi, the book is now available in English for the first time.

The 14 stories presented here offer a rare glimpse into the workings of a young writer’s imagination explores literary devices and techniques, and experiments with stream-of-consciousness, interior monologue, and multivocal narration.

The following is an excerpt from the book.

An Evening in Avadh

Strange—very strange—so, you won’t dance with me!”

“No, because you’re British and young Indian girls from respectable families don’t dance with soldiers, particularly American or British ones—it’s inappropriate. And that big hulk of a soldier who’s been lumbering around you for the last eight hours is Indian, and my uncle’s friend.”

“You Indians are very devoted to one another.”

“Of course, we are! Arrey, Jim, you’re British, a firangi—white—a turnip, a beetroot! So what if you’re handsome, the rest of you look like beetroots. As a community, you’re deceitful, and we’ll soon haul you by your ears and throw you out of our country and you can go home shedding tears of dejection. Because we’re going to get our freedom, do you understand?”

“Who’s this tiresome person talking politics in the ballroom?”

“Don’t listen to her, Jim; she’s quite… she’s a staunch Muslim Leaguer. She’ll tell you that Jinnah is the greatest man in Asia. Jim, if you really want to understand India, I’ll lend you some books—Tagore’s Geetanjali, Netaji’s biography—and apart from these the Ramayana and the Mahabharata are also quite helpful. You’ll be able to unravel the secrets of karma, nirvana and mukti; in fact, you’ll gain enlightenment yourself! And let me tell you, Jim, I don’t normally condescend to talk to any foreigner, but you’re different. That’s why I’ve invited you. Your father is a Lord, you’ve studied with my brother at Oxford, and you’re different from the rest of your countrymen. Besides, you’re handsome and charming! Your green eyes brim with romance, melancholy, suffering and mischief, all at the same time. I love your green eyes, but in spite of this I won’t dance with you. You speak really well, too, with just the right accent. You’re the first Englishman I’ve met who speaks correct and good English and can engage in meaningful conversation on any subject for a considerable length of time. Blowing cigarette smoke, you claim, like Colonel Wilde, that the three or four Indian girls you’ve met during your two or three weeks-long stay here, have impressed you—that they’re delightful. They express their opinions regarding China’s communist policies and military ambitions, and deliver long and insightful speeches about Indonesia’s freedom, with the same grace they display while dancing Manipuri, kathak or the rumba. Their movements are fluid, their expression is sweet; they are musical when they laugh, and their clothes are reminiscent of the paintings in Murraqua-e-Chughtai (Chughtai’s Album). I approve of your views. I know that despite being an Englishman you noticed my silver gharara when you stepped onto the dance floor. You should know that you’re in Lucknow where the evenings are exquisite. Avadh was actually quite a romantic kingdom. If you look back at its golden history you will see that the king played Raja Indira or a jogi in operas and music symposia. They were all hopeless good-for-nothings—that’s why this wonderfully wealthy, dream-like kingdom was usurped, snatched from them. And now all the lands that belong to these useless and ineffective taluqdars, lingering on from long-ago, will be distributed among the poor and wretched by the new democratic government, because this is peoples’ governance. Do you understand? You commended Uma’s Maharashtrian sari, said you’d like to take one back for your sister. Will she like it? You found the yellow and violet flowers in Zeenat’s chignon very fetching. Fact is, we have a knack for adorning our hair because ours is a country of flowers, fragrances and melody—understand?”

“Arrey, why are you singing India’s praises? Haven’t you just voted against the only nationalist party, you agent of the League?” “Jim, haven’t I told you not to discuss politics with her? She can’t even explain the meaning of the word Pakistan—she hasn’t been able to do so, till date!”

“But Pakistan will come into being, Miss Hyder!”

“So, one will need a passport in order to meet you. In other words, if one wants to go to Lahore, one must first go through the trouble of getting one’s passport, then run around making all sorts of payments—what a nuisance that would be!”

“Don’t talk like a fool. Anand, how silly you are; this is not going to happen! Come on, let’s dance. (The lights of the hall are dimmed for the waltz.) We can discuss Pakistan later.”

“Strange—very strange. What’s the matter, Jim? Your eyes are again like those of a petrified fledgling that can neither express its anxiety nor submit to it. Why did you push your chair back and tilt to one side, especially when such an alluring melody is playing and dancing couples are gliding around the ballroom—ghararas, saris and gowns. Join the dancing; forget about where you are and about your companions in this scintillating company. Give up your habit of reflection while you’re with us. When you return to the hunting-lodges in Wales, there will be time enough to write your book about our profligate ways, our ingratitude, our sexual and other perversions, and hold them up against your distinction, your country’s high culture, the beauty of your snow-white mountains and clear blue seas.”

“Bhai, how far will you take your contest? It’s only been an hour since you were introduced to him, but you’re chewing his brains with your argument—the poor fellow is quite embarrassed about the shortcomings of his countrymen. His green eyes are ablaze with romantic sadness, with helplessness and mischief, and his brave and true British heart wants only one waltz with you, because tomorrow morning India will get her independence and he’ll be picked up by his ears and thrown out of your house.”

The night is getting darker, and below the dais where the orchestra is playing, two white girls have begun dancing a cabaret—the evening’s last dance on the dimly lit marble floor, in the shadow of heavy yellow drapes. The melancholy notes of ‘Good night, Marie’ waft outside the large and small windows of the hall. Jim’s eyes are drooping.

Why do you dream, Jim? You shouldn’t dream. An Englishman must always be alert. Know how to operate a machine-gun. You’re a liar; such an imposter! You lie about being in love with this mystical land, resonating with Tagore’s lyrics and Uday Shankar’s dance; with its snowy Himalayan peaks and its valleys covered with waterlilies, where black-eyed girls wear silver ghararas and deck their hair with yellow and purple flowers. This is a falsehood, a lie, a great pretence. Because here, there’s filth and poverty and misery—the unbearable burden of being alive. Life has no meaning—it’s of no use! You will never understand this monotony, this jaded and weary existence. You want to sit in Mayfair’s air-conditioned ballrooms and express sympathy with India. You’re a fool! Do you understand?”

The Avadh evening turns into a cold, dark night and Mayfair’s Guest Night has come to an end.

Your eyelids are drooping under the weight of your dreams. The yellow flowers in Zeenat’s hair have wilted and fallen to the ground and we’ll crush them as we go down, each one of us. This glittering ballroom will soon be empty and all its sparkling lights will be put out, one by one, and after tonight we’ll forget you. This dark-skinned cartoonist from Madras, sitting quietly on his chair in a corner, has sketched innumerable profiles of you; and this handsome, dashing and arrogant editor of our English daily; and Anand, the radio programme director who recites English poems and bores everyone; and Uma who’s as beautiful as Hedy Lamarr and has spent the entire evening trying to explain the philosophy of Purna Brahma. She says that next Sunday she’ll publish a story about you in the Pioneer’s magazine supplement. And Zeenat, who’s a soprano and my brother’s fiancée, is going to compose a song to honour you. I’ve promised to paint your portrait and I’ll fill your eyes with shades of the azure sky, Kashmir’s green flower-bedecked lakes and dewy moonlight. Anand’s collection of poems being published in London will include some of his verses on you. But the fact of the matter is that once you leave tomorrow, you’ll be conveniently forgotten like life’s little things that are quite easily dropped.

Actually, all this is just useless small talk! You praised our paintings; appreciated our dance; listened to our music, but believe me, our musical compositions, our stories and our dances are all quite meaningless. How can they matter when life itself has become hollow? When there isn’t an end, what’s the point of worrying about means? Isn’t all this unacceptable to your matter-of-fact British sensibility? We must all seem strange to you—Uma and Zeenat and I, don’t we, each one of us? You even find our philosophy, which we call Confucianism, quite strange. In fact, it’s quite practical. Accept each day as it comes. Strange, isn’t it? Strange things can be quite attractive—you wouldn’t be here otherwise. Your humanity that made you leave your Welsh castles and hunting grounds, and your lordly father leaning his head on cushions while debating the Labour government’s budget, sitting in Mayfair discussing Vedantic philosophy or justifying Pakistan’s râison d’etre… Life, and these evenings are quite exotic. Mr. Howard and the others express their views on the impending famine, then leave their tables to dance, spend four or five hours like this, and don’t tire at all.

Uma is a very interesting young woman. In spite of being a staunch Hindu she’s married a Muslim, wears a gharara and greets you with ‘Salamalaikum’. Perhaps I’m even more fascinating, for despite being a Muslim I greet you with ‘Jai Hind’ or ‘Namaskar’—though you’ve been told that we’re likely to slit each other’s throats in the marketplace. ‘God save the King’ is playing. Stand up immediately, Jim. You’re so absorbed in talking with me that you forgot to stand up! We’re going down. Come to the portico with us and bid us goodbye after your national anthem. The night’s growing darker; the moon hasn’t yet risen behind the eucalyptus trees, and you should know, Jim, that young girls like us are frightened of dark nights for no particular reason.

The night is silent and our car is speeding along, having left behind the Mayfair portico’s cool blue lights. Far away, a shadowy reflection of the baroque, French style La Martinière College building quivers on the silent lake. Sikandar Bagh, Banarsi Bagh and Dilkusha’s expansive, lush lawns and eucalyptus groves seem so remote in the silvery moonlight. The red stone bay window of the grand bridge near the Gomti rears up against the sky, and in front of it Chhatar Manzil raises its golden cupola in silent pride while at its feet, on the Gomti’s surface, dance reflections of its ballroom’s lights.

This is an Avadh night, and in a short while, Jim, you’ll be distanced forever from these nights. Your Dakota will fly past the silvery ribbons of the Gomti, Saryu and Ganga and disappear behind the clouds over the western seas. Midnight’s feathered friend utters a piercing cry. A dreamy, magical aura fills the space. Outside the window, beyond the custard-apple trees by the roadside, the old gate stands as silent witness, its upper levels and bay windows aglow with dim lights. Far away, the chowkidar calls hoo hoo hoolaalaalaa as he keeps watch and his call echoes on Gomti’s silvery sand banks for long. The shrill call of the lark perched on the antenna shatters the silence of the night before merging into its vastness. I recall that, while saying goodbye near the staircase, Jim bent to tuck my gharara into the car and, seeing Mrs. Rahman smoking in the seat, said softly that he didn’t approve of women who smoked. He didn’t let his sister smoke because he’s British, not American, and the British are old-fashioned.

It’s almost two o’clock in the morning and near the electric stove empty coffee cups are strewn carelessly on the floor. Monotony overtakes us all. Just a week remains for our exams and a lot needs to be studied. I wonder what I’ll do with so much studying. That old gate built by the kings of yore looks taller and more awesome by night. Its grandeur is formidable; all day, beneath its stately arches, UTC jeeps ply to and fro and groups of girls walk to or from the library. I’m painting instead of studying, and Zeenat asks me why I paint. I shouldn’t paint; I should do something more useful instead, like preparing cauliflower beds in the kitchen garden. Then the governor’s wife and his memsahib will sing our praises at Governor House tea parties. Throwing her fat economics books aside, Zeenat sprawls on the carpet, idly flipping the pages of her music book while humming a silly, irrelevant couplet by Salam Machhli Shahri: “An Avadh evening will return if I live…” or something like that.

Really, we’re all quite silly!