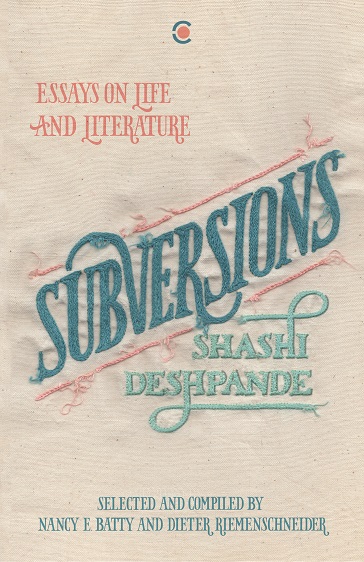

Shashi Deshpande has had a long and rich career as a writer of novels, short stories and essays. She has not only known many Indias, past and present, but also contributed to debates on the understanding of India’s contemporary social, literary, and political issues. Subversions: Essays on Life and Literature (Context, 2021), selected and compiled by Nancy E Batty and Dieter Riemenschneider, invites its readers to enter that fascinating dialogue.

The following are excerpts from the book.

Macaulay’s People

Writers rarely trouble themselves with abstract questions about writing. However, very early on in my writing career I found myself confronted by the question of where my writing belonged. A question that perhaps came out of the absolute isolation in which I wrote: I did not know any writers who wrote in English, I had not read any books like the ones I wrote/was writing, I had no response from readers to my writing. In fact, I did not know whether I had any readers at all. My writing seemed to fall into an abyss so deep that I did not get back even the faintest whisper of an echo. I had seen my father, a writer in Kannada, living in the midst of his literary world, enjoying discussions with friends, writer-colleagues, admirers, having a play reading each time after writing a new play. I remember him reading, a crowd sitting around him in rapt silence, I remember the lively discussions that often followed. When, years later, a friend asked me why I didn’t read out from my writing to a group, I was taken aback until I realised that he came from a tradition of reading/reciting poetry aloud to the accompaniments of ‘Wah Wahs’ from the listeners. A tradition that belonged to writing in the Indian languages (bhashas), not to English. (This was way before literary events and festivals.) I smiled at my friend’s ignorance, blissfully unaware that I had mentally separated English writing from bhasha writing.

However, when I read a review of Zadie Smith’s essays Changing My Mind, the reviewer’s reference to Smith’s congenial attitude to her literary past, which made the writing of her novel On Beauty possible, made me understand that this novel was her tribute to E.M. Forster’s Howards End. And that it was possible for her to connect herself to Forster and Howards End because she belonged to the same tradition. Was there any writer to whom I could connect myself in the same way? I remembered with some embarrassment that I had once, when asked during an interview about my influences, connected myself to the English writers Jane Austen, the Brontës, Mrs Gaskell, George Eliot. I did realise in time that this was not wholly true, because my writing was deeply rooted in my society. And in any case, after reading F.R. Leavis’ book The Great Tradition, I no longer dared to put myself in the company of the English writers. Leavis, in his book, traces a clear line of tradition of the Great English Novel, beginning with Jane Austen, going on to George Eliot, James Conrad, Henry James and D.H. Lawrence. With this, Leavis firmly—and rightly—shut the door in my face.

In any case, I had become aware by then that my place was in the midst of the great sprawl of Indian literature in multiple languages. Surely there was room for English among the many languages that made up Indian Literature? But it was not that simple. If this meant that I belonged to the class of Indian writers who wrote in English, something in me protested. The extreme simplicity of R.K. Narayan’s world, the self-conscious spiritualism of Raja Rao, the earthiness of Mulk Raj Anand, as well as his language, and the slight contempt for India that lay under all Ruth Praver Jhabvala’s writing—how could I put my writing among these? The language alone could not link me to them. At the same time, the bhasha writers made it clear that English writing had no place in Indian literature. That it could not belong, not only because the language, English, was the language of the colonisers, but also because it was impossible to convey Indian culture in this foreign language. And, an even greater sin, Indian English writers wrote for a Western readership, they wrote to make money. Mercenaries, in other words.

So where, then, did I belong? And more importantly, did it matter? Was it necessary to belong somewhere? It did matter. Looking back now, I can trace the struggle I had in writing my two early novels, The Dark Holds No Terrors and That Long Silence to this very fact of my being so isolated. An isolation enhanced by the fact that at the time I began writing (the late sixties and the early seventies), there was a hiatus in Indian English writing; it was as if someone had hit the pause button. The older writers were flagging and there were few new names emerging. Since I had no role models, I had to write entirely out of myself, so to say, to find my own language. Language is always a problem when writing in English about people living in India, most of whom do not speak English. Many of the early writers had found their own way of coping with this problem, but I knew that I did not want to write like any of them. I would go my own way.

[…]

We, the People of India

When, decades back, I had to study the Constitution of India as a law student, it was in its infancy, scarcely a decade old. For us students, the chapter on Fundamental Rights mattered only because it was important for the examinations. It took the Emergency for many of us to understand the real importance of these rights. Today, I look at the rights differently, perhaps with a greater understanding. Article 14, which promises all citizens equality before the law, seems remarkable when I think of what it meant to a people who, ruled by a foreign power, had been second-class citizens in their own country for two centuries. What it meant to a people who lived in a rigidly hierarchical society in which people could never hope to move up the social ladder, because caste pinioned them to their places. Where you were born, there you lived all your life. Caste was certainly no believer in equality.

But before I talk of the right to equality, I will go back for a moment to an earlier and a personal story. Many years ago, I was in Cambridge for a seminar on British literature. There were five of us from the subcontinent at that seminar, three Indians, one from Bangladesh and one from Pakistan. During a casual conversation, one of these two said to us Indians, ‘We envy you. You can stand in the middle of the street and criticise your Prime Minister’. The other heartily concurred. I imagine we patted ourselves on the back then for being a mature democracy. We had the splendid example of the time when Indira Gandhi had attempted to subvert democracy and had been voted out of power. And the motley collection of parties and individuals, who had formed a government after that, they had been voted out as well, when it was clear they were totally unfit to govern. We felt good about ourselves. What made us feel even better was that we were not like our neighbours across the border. In fact, it gave us great pleasure to define ourselves as not-Pakistan.

Then, recently, I read an interview with Mohammed Hanif, the Pakistani writer, who writes so critically and courageously about the sad state of affairs in his country. During the course of the interview, the Indian journalist interviewing him referred to a poem written by a Pakistani poet, Fahmida Riaz, who sadly passed away a few days back. The journalist quoted a line from her poem, ‘Tum bilkul hum jaise nikle (You turned out to be exactly like us)’.

Mohammed Hanif’s response was, ‘How different could we be? We drink the same water, eat pretty much the same food, we breathe the same air …’ And finally, he added, ‘It’s horrendous here, it’s horrendous there’.

It hurt to read this. It shocked me. However bad things were in our country, how could anyone say we had become another Pakistan? We had our courts, sentinels of our democracy. And a free and enormously alive press. But both Mohammad Hanif’s words and Fahmida Riaz’s poem were couched in tones of such regret, that I thought we needed to take a long and hard look at our country. What I saw was not very reassuring; in fact, it filled me with dismay.

When the 2014 elections gave the BJP a clear and strong mandate, many of us were thankful, because we were tired of corruption and coalitions. We hoped to settle down to a sensible governing, to the progress that had been promised. But we were sadly disillusioned. We entered the Era of Mobs. Mobs which came out of nowhere, it seemed, mobs who indulged in lynchings, in barbaric killings in the name of the holy cow. Mobs who turned into moral policemen in the name of ‘our culture’. Mobs who attacked people in the name of patriotism and nationalism. Mobs who imposed a kind of unofficial censorship, so that they decided whether a book, a film, a play, a painting exhibition, or a musical performance was fit to enter the public domain. These mobs seemed to have some kind of patronage, for very rarely were they punished for their crimes.