The Ministry of Home Affairs has floated proposed amendments to the Registration of Births and Deaths Act, 1969 which entails a national database of record of births and deaths and linking Aadhar information to the same. It also wishes to use this data to update the much opposed National Population Register (NPR) to ultimately make it easy for creating the National Register of Citizens (NRC). The proposal, while seemingly being a slight change in the system and process of record of deaths and births, has a larger interest at play. We discuss how these proposed changes will have a significant and far reaching impact on the wider population which lacks access to proper infrastructure and will remain unaware how a registration of birth which could benefit them in receiving welfare scheme could now put their status as a citizen of the country at risk.

The Ministry has sought the comments of the public and the window for sending in comments is open for 30 days after October 27.

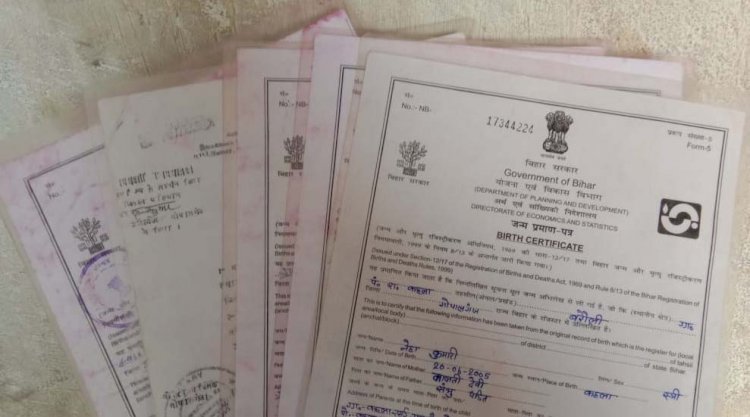

Centralised database

Through the amendments, the Centre proposes to maintain a centralised database of the births and deaths in the country, which has until now been a prerogative of the States. Now, a Chief Registrar appointed by state will keep a record of deaths and births who will also ensure that the same is integrated with the national database. Never has any government before this, felt the need to bring about such changes which is merely a parallel record of deaths and births which is sufficient for states to maintain. Centralising the database means the data will be used by the Centre for keeping it records and use it for other databases.

This has been clearly worded in the proposed amendment by way of adding a sub-section 3A under section 3 of the Act. The sub-section 3A reads as follows:

New Insertion:

“(3A) The Registrar General, India shall maintain the database of registered births and deaths at national level, that may be used, with the approval of Central Government, to update Population Register prepared under the Citizenship Act, 1955; Electoral Registers or Electoral Rolls prepared under Representation of People Act, 1951; Aadhaar Database prepared under Aadhaar Act, 2016, Ration Card database prepared under National Food Security Act, 2013 (NFSA); Passport Database prepared under the Passport Act; and Driving Licence database under Motor Vehicles (Amendment) Act, 2019 and other databases at national level subject to proviso of Section 17 (1) of RBD Act, 1969”

In section 3, the Central government can be seen encroaching upon the maintenance of a ‘database of registered births and deaths’ which was not provided for earlier.

Under Entry 3 of the Concurrent List which is part of the Schedule VII of the Indian Constitution, include “Vital statistics including registration of births and deaths.” This clearly indicates that record of registration of births and deaths was considered a topic which did not need to be assigned to just the states or just the Centre and up until now the process has been running smoothly with States handling and maintaining these records with minimal role being played by the Centre. However, since the topic is in the concurrent list, the Centre has the power to make laws on the same without having to take sanction of the states and any law made by the Centre in this regard will overrule any law made by the state in this regard, if it runs contrary to what the Centre has proposed.

The proposal also inserts sub-section 3A entrusting the Registrar General to maintain the database of deaths and births at the national level in order to update the National Population Register (NPR), Electoral Registers, Aadhar Database, Ration card database, Passport Database as well as the driving license database. Further, the Chief Registrar functioning at the State level is entrusted with the task of maintaining a unified database for integrating it with the national database.

The prime intention of the Centre behind making these propositions for amendment is to update the database of the NPR which is also the first step towards creating the National Register of Citizens (NRC).

Under section 8 it also requires that Aadhar number of parents and informant in cases of birth and in case of death, Aadhar number of the deceased, parents, husband or wife and the informant will be required to be input while recording deaths and births. This will allow the Centre to gather Aadhar information of those related to persons being born and the deceased, making it a wider and complex net of database which the Centre will possess.

Why is centralisation of this data a problem?

The Centre has clearly stated that this data will be used for updating NPR, Electoral Registers, Aadhar Database, Ration card database, Passport Database as well as the driving license database. This means, the Centre will be able to track births, deaths,

The centre will have a record of all the registered deaths and will use the same to update NPR which will in turn be used to make the nation wide NRC. However, the question arises, what about those births that are not registered?

Citizen for Justice and Peace’s experience working on the citizenship issue in Assam has led to the realisation that out of people exclude from NRC, vast numbers were children because the parents could not provide their birth certificates. Children below 18 do not have voter’s ID cards and if they have not given class 10 or 12 board examination their only proof of birth in the country is the birth certificate and if the infrastructure for registering births is not robust in rural or remote areas, it is likely that a large chunk of population does not exist on paper for the government and there is no way for them to prove that they were indeed born in this country. Hence, if this data is centralised and used to update NPR and eventually the NRC, this population has no strong proof of citizenship and stands at the risk of becoming non-citizens or aliens in the country they were born in. This, in itself, is a potential grave humanitarian crisis.

India is among the five countries – the others being Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Nigeria and Pakistan – that are home to half of the world’s 166 million children whose births have not been registered, according to a 2019 UNICEF report. In India, nearly 24 million children under five years of age did not have their births registered in the last five years, UNICEF estimated.

Dipa Sinha, assistant professor at Dr BR Ambedkar University Delhi stated that birth registrations picked up only after institutional deliveries increased in the 2000s. This cannot be ignored at all since the population born before 2000 is also at a great risk of not having their existence recorded in government records and are at a risk of having their citizenship questioned. The rate of birth registration in the year 2000 was at 56.2% which means that almost half the population born in that year did not have their births registered.

Based on information received from 32 States/UTs, share of institutional births to total registered births is 81.2 percent. This means that despite institutional births, there are loopholes whereby registration of births has been missed out.

With so many hurdles in place , infrastructural issues and lack of awareness for registering births, gathering of this incomplete data leaving a vulnerable population even more vulnerable , at the risk of being deemed “foreigners” in their own country.

Updating electoral rolls

As per figures released by Civil Registration System of the Office of the Registrar General of India, level of registration of births has increased to 92.7 percent in 2019 from 84.9% in 2017. While the increase is significant and creates hopes that one day all births in India will be registered, the 92.7% registration still leaves 7.3% of children whose births have not been registered.

Under Article 324 of the Constitution superintendence, direction and control of the preparation of the electoral rolls for conduct of elections are powers exclusively vested in the Election Commission (EC). The MHA is prying over the EC as well when it plans to keep updating the electoral rolls with this centralised database. This will not just make it a tedious and confusing process but will also make matters difficult for the EC as it would have to depend on MHA for such data and depend solely on this data when EC remains an autonomous body, the independence of which is a key aspect of our democracy.

Linking Aadhar with deaths and births

Once again the government is surreptitiously trying to link the Aadhar with other government policies and programmes, which are unrelated to the intent of the Aadhar Act. The Aadhaar card, with its Unique Identification Number, at its inception was an identity document meant to be a means for inclusion. The Act itself is called The Aadhaar (Targeted Delivery of Financial and Other Subsidies, Benefits and Services) Act, 2016.

In Justice K.S.Puttaswamy(Retd) vs Union Of India a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court had examined the constitutional validity of the Aadhar Act and also held that Aadhar does not violate one’s right to privacy. One of the many contentions in the petition was the linking of the Aadhar which was being made mandatory. The court however only upheld the linking of Aadhar for paying direct taxes and for social welfare schemes including Public Distribution System (PDS). However, it said that Aadhar cannot be made mandatory for opening bank accounts or for children seeking admission in schools or even by telecom companies seeking Aadhar of their service users.

When all these were struck down by the Court, is the Centre’s move to make Aadhar mandatory for births and deaths valid? It is merely another attempt being made by the Centre to make a centralised database of all kinds of information that it can have on its citizens and make a repository of all this data in absence of any data protection laws, putting the privacy of billions at risk.

The proposed amendments may be read here: