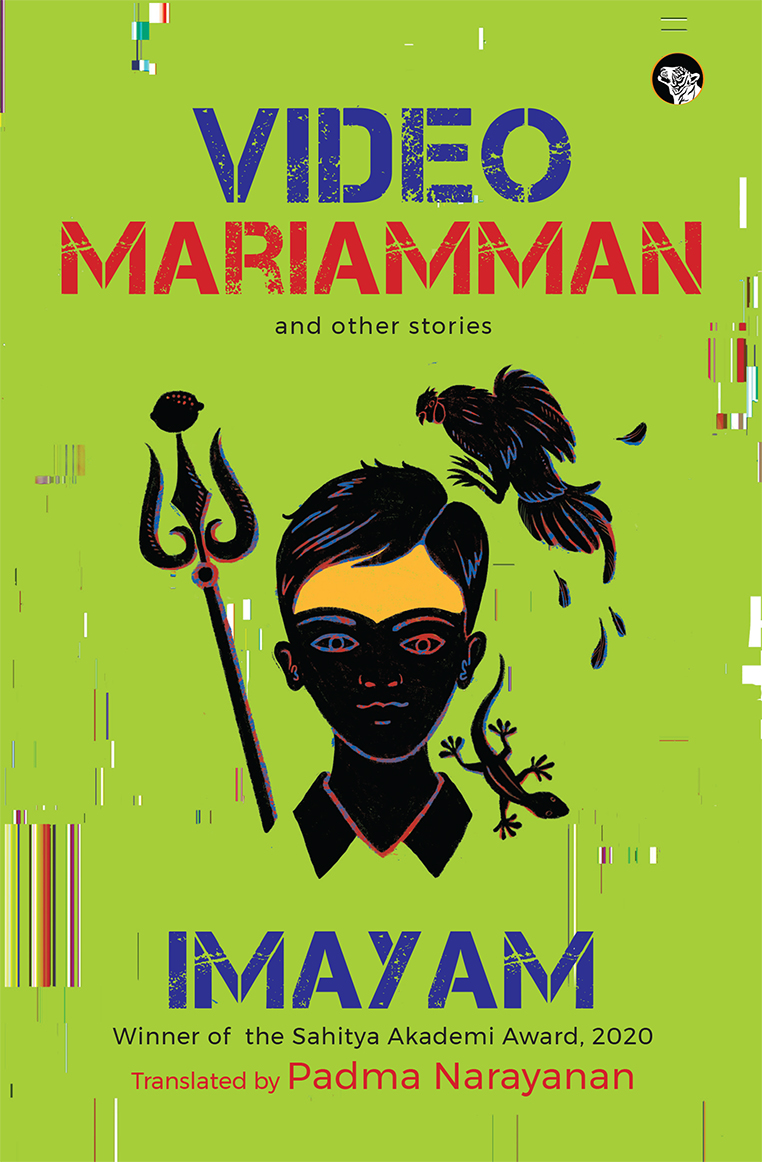

Tamil writer Imayam’s Video Mariamman and other stories, translated by Padma Narayanan, is a collection of fourteen stories about the brutal complexities of the caste system and patriarchy.

In ‘Food for the Dead’, Poonkothai goes looking for her daughter who has eloped with a ‘low-caste’ man, hoping to give the daughter her certificates and some money so that she can lead a decent life.

The following is an excerpt from the story.

Poonkothai looked down. Her tears fell on the ground. She wiped her nose with the corner of her sari. With her head lowered she said, ‘I melt all my heart’s misery in tears. If I give these things to their owner, I can die. The trouble I have taken to hide her certificates is not little. Because if, out of rage, these papers are burnt, her life will be ruined. She will be an orphan, with no one to help. It is easier to devour fire. If my sons see the papers, the very next minute they will be ashes. I will be glad if I go mad! That’s what I keep praying to that god for. That god refuses to lend an ear to what I say.”

‘Don’t cry, amma. You will faint,’ said Kamala as, prompted by who knows what, she moved closer to Poonkothai and wiped away her tears. ‘Parents think, plan something, but the children think something else. One has to witness all kinds of things until one dies. Forget it, ma. Don’t cry. There is not a single house in this world where such things have not taken place. Every month two or three girls from this school run away from home. If you were to hear those stories, you would find yours very ordinary. Girls studying in ninth or tenth standard run away. Do you know what happened last week? A girl from the tenth standard, who had a crush on an actor, went to the temple and tied a thaali around her own neck!’ said Kamala, and tried to comfort Poonkothai.

Two days before she left home, a crow sat on the roof and cawed. I thought news of a death might come, but the curse fell on my own family. I didn’t think the whole family would die like this.’

‘Okay, did you at all enquire about that boy?’ ‘I have been up and down the steps of all the photo shops in Vriddachalam. Yesterday I scoured all of Neyveli. The day before yesterday I roamed around Ulundurpettai. The wanderings I’ve done! Over the past four days, I have roamed everywhere, allowing myself no respite.’

“What kind of a boy is he? Do you know anything?” We know the boy. He never will bend his back to do any solid work. He walks erect; holds his head high. He never heeds the words of anyone in the village. If he puts on his shirt in the morning and goes out, he’ll be back only after the place has gone to sleep. A loafer around town. Doesn’t own even a quarter kani of land, not a cashew sapling to call his own. This girl has put her faith in an empty-handed fellow. He takes. photos, shoots videos, for that he keeps going from town to town. That is all the work he does.’

‘How did he and your daughter get to know each other?” They couldn’t have met in the village. If they tried that the people would have chopped them up. It seems that he went to her college to take a group photo a month ago. They got to know each other from then, it seems.’

‘Just one month and she has run off with him?” “That’s a woman’s state of mind, I suppose.”

‘Okay. To which town does the boy belong?’

‘Our village.’

‘From the same caste?’

‘There would be no damn issue then. Peace would be restored in a month or two. Even if she had eloped with an upper-caste boy, it might have been acceptable. A lower-caste fellow-that’s what made the entire village stand up against them, crying for revenge, threatening to chop him down. Even if he had been from some other town, there would not have been so much of an uproar. The boy’s mother would not have died. Destroying things in the shop, a police case filed and money also wasted, all that would not have happened. There seems to be no end to all the hullaballoo happening…’

‘The boy’s mother died?’

‘Aiyo! Aiyo!’ Kamala slapped her own cheeks.

‘It is to cut off my daughter’s breast, that my husband and sons with other people of our caste have been running around, from town to town, looking for her.’

‘Oh, my god! My insides are churning,’ said Kamala and covered her mouth with both her hands. She was trembling as if someone had pushed her off a mountain cliff. ‘Looks like I have come to work in a place where murderers abound. Caste fights do occur in my village too; but it isn’t as bad as this,’ said Kamala.

‘If anyone marries a low-caste man, she will have her breast chopped off. They have already chopped off the breasts of two women. With my daughter it would make three.’

As something occurred to Kamala, she asked sharply, ‘If the girl runs off with a man of the same caste, will they cut off her hair?’ She spat on the ground and asked, ‘Why would they cut the breast?’ Kamala was beside herself with anger. ‘A breast is a woman’s face.’

‘Instead, beat her to death; poison her. But they cut off her breast, her hair-what sort of practice is this? To a woman, her breasts and hair are important. If they are cut off she will choose to die of her own accord.’

‘But isn’t there a limit?’ raged Kamala. ‘Even after knowing that she will have her breast chopped off, she has chosen to run away,’ said Poonkothai and looked at Kamala. Tears brimmed in her eyes. With some thought hitting her, she picked up the sand from the ground and showered it on her head. Who knows when her breast will get cut off? When her corpse and mine will be burned in the cremation ground? It is better that we die soon. Even when my father, my mother died, I did not shave my head.’ She picked up the sand and flung it on her face. Poor woman, poor woman,’ said Kamala and dusted the sand off Poonkothai’s face with the end of her sari. Tears poured from Kamala’s eyes. Seeing Ponnamma coming back with the tea, she went to her and brought back two cups of tea. She gave one cup to Poonkothai. Poonkothai did not drink the tea. She kept it by the side with the glass of water. It is just hot water. Drink some. You will get some strength.’ Poonkothai sat quietly, ignoring her persuasions. Kamala finished her tea and asked, ‘It would have created a big issue in the village, no?” We’ll know what is to happen only when the party is caught.’ ‘Under these circumstances, it is not good for you to be moving around like this.’

‘But I am not able to sit at home.’ She looked here and there for a while. Like never before, in a subdued voice, she said, ‘If my son had run away with a low-caste girl, I wouldn’t face so much trouble. He is a man. He will earn his living doing any manual job, hauling sacks. But she is a girl. The world will look for what is inside her sari wherever she goes.’ Tears fell from her eyes. She did not pay attention to them. Neither did she wipe off the mucus that was running from her nose. I’ve not been able to swallow a mouthful of kanji these twenty days. I’m not able to lay my head down on the ground. I’m not able to stand in one place. I have no sense of day or night; I’m not even aware of when the day breaks or when it gets dark. I have to give her what belongs to her; that’s what is making me run around. Why would I want to see her after that? When she left the house did she even think of me?”

Now, she heaved with sobs. Kamala did not feel like stopping her. But she thought she should say something. So, ‘It’s hot here, move over a little, amma,’ was all she said. But Poonkothai sat, not bothering about the sun beating on her bare head or the sweat flowing from it. Hoping to make her talk, Kamala said, ‘You haven’t drunk water, or the tea either. Look how the flies are hovering around it.’

Wouldn’t a mother who has given birth to her, know what should be done at the appropriate stages of adulthood? Is my heart made of stone? She was the one intent on continuing her studies. Do you know how my husband and sons celebrated every time she came out successful in her exams? They let her study, ignoring what the people of the village said. They bought her everything she ever wanted.’

‘The sun is too harsh. You are sweating so much. Just move a little, amma.’

‘Never mind the sun, am I facing its heat for the first time?’

Then, seeing Ponnamma come with a bundle of papers and go from room to room, Kamala asked loudly, ‘How much more time is left? Shall I ring the closing bell?’

Just half an hour more. Until then you sit near the tree, save your legs from pain. Make sure that the tree doesn’t fall off, said Ponnamma as she walked off. Hearing those words Kamala got very angry, but she sat without venting her anger.

‘Even if she had become like the goddess who saved the honour of the people, I would have lit a piece of camphor and poured water on my head, giving up all thoughts of her.’

‘What is it, about the goddess who saved honour, that you are speaking of?’

‘It is something that happened in our village. Some twenty, thirty years ago a girl from my caste formed an alliance with a man from the colony.* The matter came to light in the village and people got to know about it. They held a village panchayat, for caste mediation. In those days people did not approach the police like they do now. All issues got resolved by the mediators of the village and caste. In that panchayat, they said, “Your relationship with a colony man has made the village lose its respect, honour. Neither can you be married off nor can you be allowed to stay in the village. So, you go, die on your own; or else the village will put you inside the lime kiln and burn you.’

‘What a murderous set of people!” Kamala expressed surprise. She was amazed to see Poonkothai sit there oblivious of the heat, sultriness, sweat, sweltering breeze or at all. Though her eyes wandered now and then towards the headmaster’s room, her attention was on Poonkothai’s story. So to make Poonkothai continue she prompted, ‘Then what happened? Those words were like digging up a spring.

The girl said, “I don’t want to be burnt by the village anything or the world. I’ll myself go down into the kiln and turn into ashes.” She was true to her words.”

“You speak the truth?’

‘On the heads of my three children, I promise you. The whole village was taken aback to see her burn herself in the brick kiln. The entire village got together and considering that she had burnt herself in the kiln to save the honour of the clan, the honour of her village, they built a temple on the site where the kiln was. Though her real name was Kalyani, because she had saved the honour of the village and clan they named her “goddess who saved honour”. She is the most powerful goddess in our village now. She blesses those girls who are not married with the prospect of marriage. She is the Sami who gives a child to a childless woman. If a woman finds that her breasts have no milk, and goes and prays to her, milk will sprout from her breasts like from a spring, nonstop.’

You are not able to talk. You are choking. Just take a sip of water,’ said Kamala. Poonkothai sat there not paying attention to Kamala’s words. Suddenly, she spoke in a dry voice, “That boy has not taken my daughter away. It is the god of death, Yama, who has taken her away. She has run off just to die. That news is yet to come to me.’ Even as she spoke her body trembled slightly. Kamala saw that and held her hand in a firm grip. Poonkothai murmured, ‘The whole village, the whole world wants to see my daughter die.”

‘If you keep thinking all the time about those two who have run off, it looks like you’ll die.’

‘She has gone to buy the sea, let her. Am I stopping her? That girl, before running away, if she had taken some money, her certificates and everything, would I be running around like this? She has taken off and flung away even the one-sovereign chain that was around her neck,’ said Poonkothai and looked Kamala in the eye. ‘If she wishes, let her consider that I am the one who gave birth to her, and come and see my face on the day of my death. Or let her just not come, it does not matter. Are we going to see who comes and who doesn’t come once we are dead?’ She stopped talking and lifted her head to look at the sky. Then, in a hushed tone, she said, ‘Even if she comes she will come into the village only as a corpse.’

‘What are you saying, ma?’

‘Any day she comes to the village, she can come only as a corpse. Men are still going from town to town, looking for her. The people of our village will find a needle even in darkness. Wherever she is, they will kill her. They’ll chop off her breast. Just to ask her to go away to some distant land, I go about carrying this money.’

‘It is your own daughter, no? Leave her alone. Let her be alive wherever she is.’

‘You don’t know them. Just four days ago they performed her funeral rites. The very day she ran away, my husband and my sons shaved their heads; they shaved mine as well. They set up a death pandal in the village; beat the death drums. They carried her photo, her saris and other clothes tied like a corpse to the cremation ground and burnt them. The ritual of sprinkling milk has also been done. To the acclaim of the village people, all rites have been done. They printed ritual notices saying that my daughter had died and distributed them to all the neighbouring villages. The whole village got together and did it all, amma.’ Poonkothai put her head down. Her body was shaking slightly. Even after Kamala had called her ‘Amma! Amma!’ several times she did not raise her head. Only after Kamala persuaded her, she lifted her head. With great anxiety Kamala said, ‘Why did you go all quiet, ma? If something happens to your life, what am I to do? And moreover, this, a school…’

‘Four days ago the sixteenth-day death rites were done. With the sprinkling of sesame seeds and water at the banks of our creek, the rites were done. On the eighth day rice, as part of the death ritual, was offered and the crow came and ate it. I also ate that offering, amma. They pasted posters and photos saying, “homage with tears”, all over the village.’

‘Did the whole village know about it?”

‘The villagers got together and made the offering for the eighth day. They all ate the curry and rice that had been offered. I also ate it.’

All of a sudden Kamala was afraid. She started to tremble when she thought someone might come looking for Poonkothai. ‘Under such conditions you have made a grave mistake by coming here. Go now. Go home. You say that they chopped off the woman’s breast, shaved their heads and all that. That scares me! If I get any news, I’ll let you know. You go first of all to the road.’ Kamala said and got up in haste.

‘Did they bear her in the womb? Did they nurse her? Clean up her shit and urine? Wash her soiled clothes? From the time she came out of my belly, were they the ones who slept by her side? Did they give their lives for her? I combed her hair; tied her sari; washed her menstrual cloth. I was the one who did every damn thing for her. That’s why I keep wandering around,’ said Poonkothai as she got up and began to walk like a mad woman.

Kamala went in and rang the closing bell.