My body in bliss, a river of wine

My eyes are open, saqi, come fill these cups

Hu hu ha!

I cry, madness in my heart.

Lal Ded, Habba Khatun, Rupa Bhavani, Arnimal: these four women poets, dating from different periods in the history of Kashmir, are household names in the valley and are claimed by all, no matter what religious, ethnic or other group they belong to.

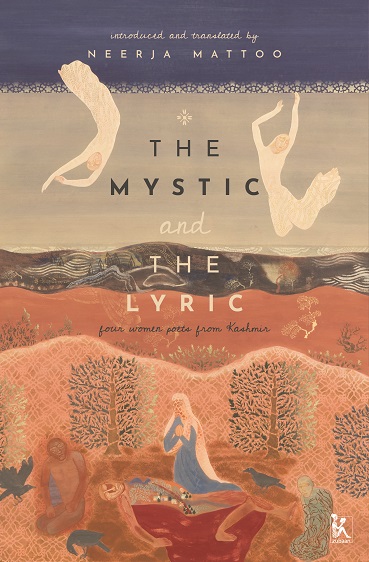

In The Mystic and the Lyric, Neerja Mattoo brings their work together for the first time, placing it in two traditions, the mystic and the lyric. Translations of their poems are accompanied by brief introductions to their work that place the women in a historical context and deal with both the facts and the beliefs about their work.

The following are excerpts from the book.

Four women poets have helped shape Kashmir’s literary imagination. In my mind, each has a distinct image, rooted in the stories I heard as a child. Lalded I see as all thought, walking through towns and villages, a naked, shapeless body, the folds of her lower abdomen drooping over her thighs. Habba Khatun appears crowned and her headdress plumed, sometimes as queen, sometimes as courtesan, in majestic robes, strolling over hill and dale. Rupa Bhawani is a radiant face, framed by hair loosely rolled into matted strands, a tapasvani meditating in caves and at lonely heights. And then there is Arinimal, draped modestly, but in a vivid peacock-feather hued shot-silk or cherry red-velvet pheran, standing forlorn against the background of a mud-brick house set in a green valley or against the backdrop of the Mar canal in the Rainawari suburb of Srinagar.

These shared images help us to understand the life and work of these four women poets. The lack of concern with adornments of the mystic Lalded contrasts with the pride in her physical beauty and exquisite robes of the romantic Habba Khatun. Rupa Bhavani, or Alakeshwari—the goddess with locks of hair—is absorbed in the quest for self-realization while Arinimal is invested with the romance of loneliness, a brooding reproach in her eyes for the forever absent lover.

As poets these women inhabit not just the collective memory of Kashmiris but are part of their living oral tradition. Folk singers begin their performance with Lalded’s vaakhs (quatrains). Arnimal’s pain of unrequited love and Habba Khatun’s complaints about her in-laws are ironic wedding vatsans or songs. Rupa Bhavani’s sites of meditation are now shrines where her vaakhs are chanted in annual celebrations. The linguistic felicity of Kashmiris, their talent for the apt word, potent proverb and rhyming analogy, is a legacy of these poets.

The origins of the two main streams of Kashmiri poetry are the mystical compositions of Lalded (14th century) and the romantic, secular lyrics of Habba Khatun (16th century). Lalded was followed by Rupa Bhavani (17th century) in the mystic tradition, while Arnimal (in the 18th century) was heir to the romantic love lyrics of Habba Khatun. Each of these women charted her particular course in life and art, refusing in her own way, to submit to the roles assigned by contemporary society. Two walked out of their marriages and the culture of silence to express their spiritual yearnings in verses of solemn beauty. The other two, separated from their lovers, openly spoke about their physical longing in the poetry of unforgettable songs. It helped that Kashmiris give mystics the liberty to break social taboos, the broken-hearted space to lament, and to treasure both.

These poets belonged to very different times, yet there is a similarity of concerns and expressions to be found in their works as well as a unique, individual note. At first glance, a common spiritual quest informs the utterances of Lalded and Rupa Bhavani, both of whom have the stature of saints in Kashmir. But the linguistic and stylistic tools each used, and the tone of their voices, is significantly different. Lalded’s language is easy to understand in spite of the esoteric thought that lies within it. Perhaps her vaakhs, having travelled down the centuries in an oral tradition owned also by the unlettered, have had their vocabulary simplified in recitation. Rupa Bhavani’s poetry, in contrast, was written down and preserved in its original, Sanskritised form, and therefore remained the possession of the Kashmiri Pandit intellectual elite.

While Habba Khatun and Arnimal might both appear to sing of nothing but lyrics of lovelorn souls, their perceptions, attitudes, representational methods and allusions are not the same, but products of different socio-cultural traditions and milieus. One was a Muslim in the 16th century Moghul Kashmir, the other a Kashmiri Pandit in 18th century Kashmir ruled by the Pathans. Habba Khatun’s poetry alludes to the Quran while Arnimal appeals to Krishna. Habba Khatun celebrates her own beauty and nature while Arinmal is more modest and self-absorbed.

[…]

Lalded

Lalded was born sometime between the second and the fourth decades of the 14th century, when Islam had come to Kashmir in a gently persuasive manner. The Saiva practices were still largely present among people. But traditional Hindu/Brahminical beliefs were challenged by the Islam of the Sufis, for whom Kashmir was a refuge from religious persecution in their homes in Iraq and Iran where they were branded as heretics. It was not a conflict of creeds but a time of religious debate and philosophical controversies, a disturbing yet exhilarating atmosphere for those bothered by the desire to know the unknown. The two religious systems or schools of thought were beginning to learn to come to terms with each other in an atmosphere of intellectual freedom. Instead of generating hatred or bitterness, attempts were being made to understand and synthesize the essence of the two systems. Similarities were discovered between the branch of Hinduism known as Saivism, practised by the Kashmiris, and the practices and beliefs of the Sufis. The result was the founding of the Order of the Rishis or Kashmiri Sufism.

[…]

Aami pana sodras naav chhas lamaan

Kati bozi Dai myon meti diyi taar

Aamen taaken poni chhum shramaan

Dil chhum bramaan gara gathsaha.

With strands untwisted I tow my boat

I wish He’d hear and pull me over

Water seeps through my unbaked bowls

O how my heart longs to go home!

[…]

Charman tsatith puni paanas

Tyuth kya vavyoth phalihi sov

Mudas vwopdish gay rinzi dumatas

Kani dandas gor aaprith rov.

All you did was stretch your own skin taut, peg it down

What had you sown to expect a bounteous harvest?

Preaching to a fool is pelting marbles at a rock

Fruitless as feeding jaggery to a bull.

[…]

Shishiras vuth kus rate

Kus bwoke rate vaav

Yus paanths yendriyi tselith tsate

Suy rate gate vaav.

Who can stop the icicles dripping in winter?

Who can hold the wind in his fist?

Whose hand can crush the five senses

Is the one who holds the sun in darkness.

[…]

Rut ta krut soruy pazem

Kanan na bozun achhen na vaav

Oruk dapum yeli vwondi vuzam

Ratandeeph prazalem varzani vaav.

Let good or evil befall if it will

The ears will not hear nor the eyes see

When the voice calls me from within

My lamps’ll burn bright, through storms adverse.

[…]

Habba Khatun

With Habba Khatun (1553–1605) we enter a world of great lyrical beauty. She is responsible for the rise of Romanticism in Kashmiri poetry. Her love and knowledge of music, the ‘Sufiana’, which is the classical music of Kashmir, enabled her to set her own songs to music. Her poems are, therefore, not only the possession of the elite but an important part of the repertoire of folk-singers, and are known to all Kashmiris, whether rural or urban. They tell of a lover’s longings, the agonies of separation and the joys of union. While tracing the emotional life of a woman, her poems become her autobiography.

All the major periods of her unusual life have been chronicled in her lyrics. She begins as a young woman celebrating the beauty of nature in Kashmir. Her brief first marriage to an unlettered villager far inferior to her in sensibility and awareness, leads to physical and emotional abuse, but does not destroy her creativity. She sets down the sorrows of a sensitive, under-privileged daughter-in-law and wife in a traditional Kashmiri household.

[…]

Her poems are filled with observations and insights on the work women do – from gathering herbs in the woods, to fetching water and spinning yarn. Another strong theme that runs through her poetry is the plight of the woman lover, bound by tradition, custom and social constraints. She is painfully aware of the social constraints and the many restrictions on women.

The birth of a daughter snares you in a web

The birth of a daughter is a smear on your name

A lion you may be, but a jackal you become.

Wake up my jewel, from your sleep.

[…]

Poshi baagas dimasay von he

Madun kor kunaye gov.

Chon firaaq chum lalavunaye

Son kun te lagi hee naav

Vanta kath kyuth myon aasunaye

Madun kor kunaye gov.

Oths zuv myon gathsun Goths lasunye

Poths nay yor rozuni aav

Kaeli aasyam gara gathsunye

Madun kor kunaye gov.

Ratsa tuli tuli rudum chhonye

Matsi nahaqan gom taav taav

Von Sahibas Habba Khotuniye

Madun kor kunaye gov.

This pain of your separation is what I must bear

Why will you never come this way?

Tell me, now what do I live for?

Where did my love hide himself ?

This fragile self has not long to live

The guest I wait for is yet to come

Soon I will have to leave this place

Where did my love hide himself ?

Whatever I gather is never enough

Whatever I do they taunt me, she’s mad

Habba can only pray to her Lord

Where did my love hide himself ?

[…]

Rupa Bhavani

Rupa Bhavani (1625–1721) too was born in a Kashmiri Brahmin family and was quite well-versed in Sanskrit and classical Persian literatures. Kashmir was ruled by the Mughals at the time and Persian was the official language and it influenced her vocabulary. Of significance is the fact that, like Lalded, she dialogued with prominent Hindu and Muslim mystics of the time like Rishi Peer, Mohammad Sadiq Qalandar and Baba Asraruddin Quadiri, prominent Sufis and rishis, who acknowledged her spiritual power. Her body, like Lalded’s, is said to have disappeared at her death.

[…]

Nav taravaavsavara

Na rang navarn ta naguthur

Bronhannyendaypatakarvaray

Kohandaydari ta kas dare.

Boat crosses river, with wind as its ferryman

Colourless, casteless, of no clan

Weed your field before planting your seeds

Then who gave the credit and whose is the debt?

[…]

Aagar grezith tai nad sedum

Baana burim tai poorim khaesi

Khen kamaah tai? Vepa nar

Buri buri tai ceyiv yakhlaase.

I thundered from my source and flowed like a river

I filled every vessel, every cup on my way

Who will drink from them? Only those who can

These cups, I have filled them to the brim, drink!

[…]

Kuni na tamaahe kunina takabure

Shamiyuth sore pure rav

Pal pal pali tai tas na mure

Vaetit vaates pure rav.

Desire nothing, take pride in nothing

Contain the senses, and the inner sun will rise

Grow with each moment and lose nothing

Reach that state and be full as the sun.

[…]

Arnimal

Arnimal (1737–1778) is a poignant voice, singing of unrequited love in musical lyrics of great beauty. She lived when Kashmir was under the Afghans who ruled through their governors. A Kashmiri Pandit, her husband was a Persian scholar as well as a successful man of the world who had little use for the sensitive Arnimal. He was an ambitious man who rose to be a luminary in the court of the Afghan king who ruled Kashmir through his governor. Thus, he spent most of his life in Kabul while his wife pined for him. The loneliness and yearnings of a young wife deprived of her husband’s love are some of the themes of which she sings unabashedly…

While Lalded and Rupa Bhavani were married to men far inferior in intellect, and Habba Khatun according to legend, to almost a village idiot, Arnimal’s husband was a scholar, poet and linguist, a sophisticated member of the courtly circle of the Afghan governor of the time, Jumma Khan, who himself was interested in music and poetry and therefore a patron of poets. But still the husband, Bhavanidass Kachru, had no use for the sensibilities of his wife and did not appreciate her poetic skill. Perhaps, the unpretentious lyricism of her songs in the language of the people—Kashmiri—did not appeal to his serious, purposeful, even moral view of poetry. Ironically, Arinimal’s songs reached out of her closet through time and place, and are sung today, while her husband’s Persian magnum opus Behr-I-taveel lies forgotten in some archive. Clearly, women’s voices have a way of escaping stifling silences!

[…]

Arnimal’s work has more than a few surprises for us. She lived at a time when Kashmiri society must have been under great strain, living under Afghan rule, where feudalism and patriarchy were in full strength and even the privileged did not have the liberty of voicing their feelings. It is astonishing, therefore, to find a woman, particularly one from a conservative Kashmiri Pandit family, doing so, uninhibitedly in her poems. Here we see a woman who would not submit quietly to ill treatment in a patriarchal society, nor allow herself to be banished to the attic as a madwoman. She protests against his cruel spurning, exposing his faithlessness in unsparing words and in the process we hear songs of great beauty. It is the wail of a victim of patriarchy in its various forms, in which there is no compassion, only mockery for a woman discarded by her husband:

My garment is soaked in tears, wild one

I wait, lovesick, while the days drag by

I came dressed up and adorned for you

In what madness did you run away?

I’m spurned, scorned, and taunted

I wait, lovesick, while the days drag by.

[…]

Goon goon mo kar ha yendaro

Kanaren pholilah malaye lo.

Rabi tala kaer tul sumbalo

Yamberzal pyaala heth praaraan chhay.

Heethar chhas nay dubaara pholayo,

Goon goon mo kar ha yendaro,

Kanaren pholilah malayo lo.

Hum not with pain, my spinning wheel

I’II soothe your aches with scented oils

Hyacinth, lift your head from the mud

The narcissus waits with her brimming cup

A jasmine bush am I, I will not bloom again

Hum not with pain, my spinning wheel

I’ll soothe your aches with scented oils.