The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), passed by the Parliament of India in December 2019, promises citizenship to migrants of the ‘Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi or Christian community from Afghanistan, Bangladesh or Pakistan’. By excluding Muslims from the list and not extending the promise to refugees from any of India’s non-Muslim-majority neighbours, the CAA makes religion the basis of citizenship for the first time in the history of the Republic. Many fear that this Act, coupled with a countrywide National Register of Citizens (NRC), will eventually be used to disenfranchise India’s Muslims, or to trap them in a permanent state of fear and insecurity, which has been the fate of millions of Bengali-origin Muslims of Assam.

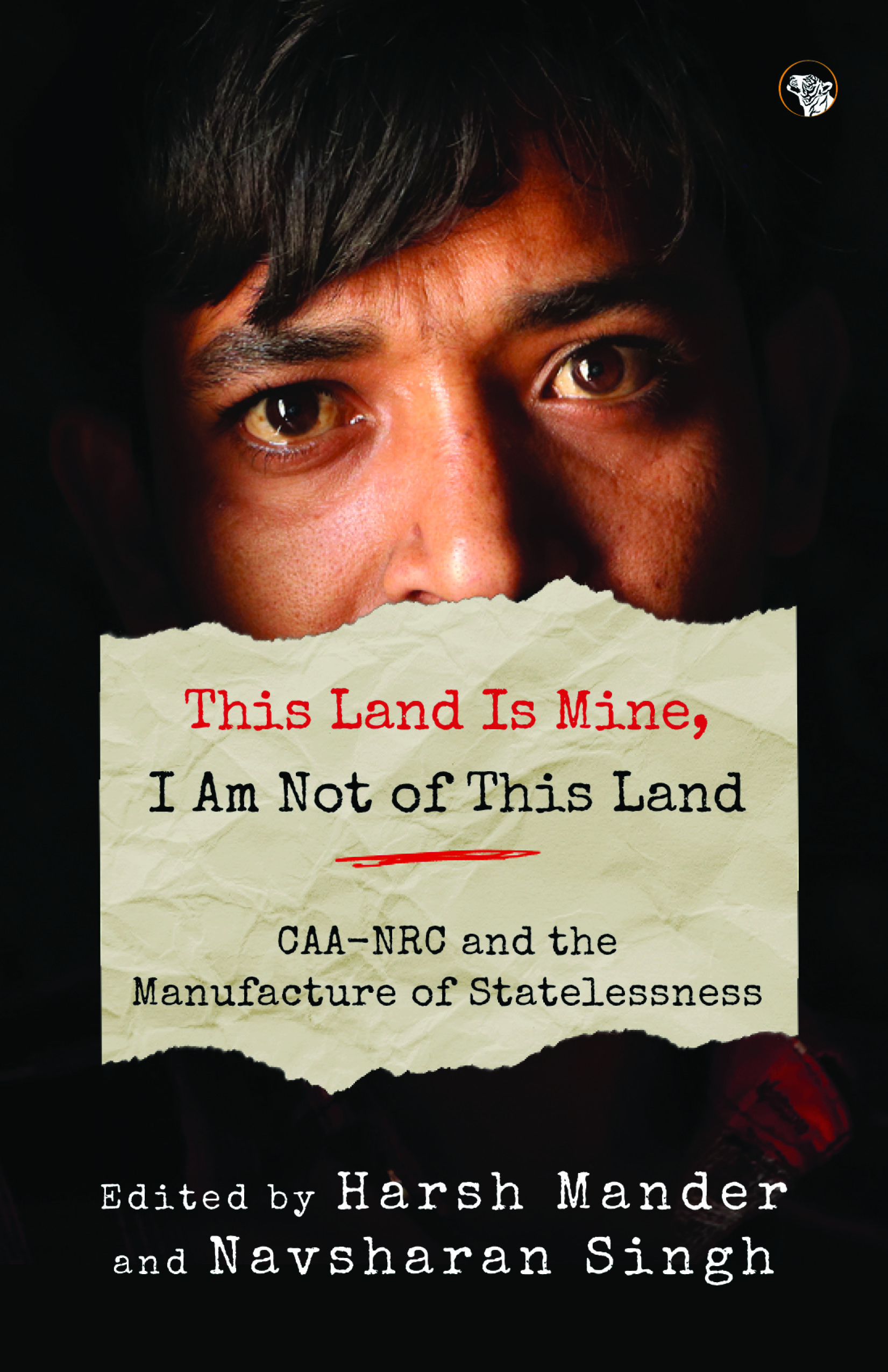

Edited by Harsh Mander and Navsharan Singh, This Land Is Mine, I Am Not of This Land brings together a comprehensive selection of essays that deal with the theoretical, political and subjective aspects of this issue. The book argues that with a key value like citizenship in question, it is not just the destinies of India’s citizens but the very democratic foundation of the Republic that is at stake.

The following are excerpts from Varna Balakrishnan and Navsharan Singh’s essay.

Khairun Nisha

Khairun Nisha of Mulagaon district (name and location changed) was all of 15–16 when she was married off. She went to live with her husband in his village which was a few kilometres away. They lived in the village for about two years where she delivered a baby girl at home, and when their home was washed away in the floods, she came to live with her natal family with her husband and the baby girl. They stayed on there. She had two more babies born to her in her parents’ home, both boys. When her youngest was two years old, and she was 26 years old, she was declared a D-voter. She didn’t know how it happened because none of her siblings were marked ‘D’ nor was her husband. Perhaps the Border Security

Force people went to the husband’s village and no one could verify a young girl Khairun Nisha as a resident of that village.

Her grandfather had been a resident of Rangapani from the late 1930s and the family had all the records to show that they were inhabitants of the village. The legacy documents were all there and with some effort they were also able to furnish documents showing the linkage. Mind you, it is not easy, as we might think, for women to prove that they are their father’s daughters. How can you? You are never required to have a legal or civic identity—Khairun didn’t have a birth certificate nor a school certificate which mentioned ‘Khairun Nisha, daughter of Md…who was the son of Md…the son of Md…’ whose name is included in the Nazul record of 1938. Her nikah was never registered and the nikahnama given by the village maulvi is not admissible as proof of residency in the NRC list of documents anyway.

Also watch | Book Launch: This Land is Mine , I Am Not Of This Land

But the family made a valiant effort and were able to get a document which identified her as a daughter of her father, as all her other siblings were. Armed with this proof, they started representing her case in different offices, but the newly acquired document was not deemed a proof of her residency, and in 2009, the Foreigners’ Tribunal declared her a foreigner and she was sent to the detention centre in Kokrajhar, at a distance of approximately 125 kilometres from her village.

It’s been 10 years and Khairun Nisha, an ‘illegal Bangladeshi infiltrator’, continues to languish in the Kokrajhar detention centre. Her little boy is now 12—she has seen him only twice in these ten years and he did not recognize her. The other son is 15 and works in Meghalaya’s notoriously exploitative construction sites. Her daughter who was married off two years ago and has been bringing up the two boys by working as a domestic help, has also seen her mother only a couple of times in these years. As for the father of these children, the husband of Khairun, he couldn’t cope with the disaster that befell the family when Khairun was arrested. He became sick, neither eating nor sleeping well. In the ten years that Khairun has been in the detention centre, he did not visit her even once. He couldn’t bear to see her there, he confessed. And this man died a month ago. Khairun has not been told of his death. As it is her eyes have rotted from crying endlessly all these ten years—perhaps she has been crying for all of us, because we did not shed any tears when she, the opposite party, OP, as they are called in official language, was taken away by the police from the Foreigners’ Tribunal.

Khairun is now 35 or so and, following the recent Supreme Court order that those who have done three years in the detention centre should be released, would soon be coming home. But when Khairun, the alleged foreigner, the illegal Bangladeshi, finally does come home, after ten long years, and is reunited with her family, one might imagine everyone would feel relief. But we will only have to hold our breath longer, more deeply. Because she will realize that she had only made it to the starting line of another long, arduous and volatile legal process that is difficult to predict or prepare for. She will be released on conditions which include two sureties of one lakh each, weekly police reporting, and, perhaps a magnetic tracking bracelet or anklet, which the Chief Justice proposed in a discussion on the matter. The family has arranged for the two sureties but for the last two months have been waiting for the permission from the state Home Department. When asked about the tracking band, the family was very upset and thought that it would only add to the distress of all of them.

Because of her detention, despite the family presenting the full family tree and legacy and linkage documents, 52 members of the family did not find their names in the NRC list which was declared on 31 August 2019. Besides her release, they are running around preparing to file an appeal. An arbitrary and callous stamping of ‘D’ on Khairun’s voter card has led to a monumental crisis for the entire family.

She will learn that her two sons born after 3 December 2004, to her, a ‘declared foreigner’, according to Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi’s order, will also not be entitled to have their names included in the NRC and they will also be declared foreigners—illegal immigrants.

We met Khairun’s family on 17 November 2019 in their home in Mulagaon district. Khairun’s mother didn’t stop crying the entire time, as if asking us why? Why did it have to be this way? The sad thing is, it didn’t have to be that way, nor should it.

[…]

Swati

Swati Bidhan Baruah, Assam’s first transgender judge, and president of the All Assam Transgender Association, highlights the specific lacuna that trans people fall in under the NRC. ‘Most of the transgender persons have been abandoned. What is more, the transgender person has to struggle with their own identity, in society and within the family. When a trans child has been thrown out or has been abandoned by their own parents and handed over to trans groups, a child comes within the culture of a matriarchal tradition or a transgender tradition.

So, in such a situation, documents that prove lineage between the parents and the transgender person, that too from 1971, is very problematic.’ This estrangement from the birth family

and the adoption of a new family, under a gharana system, can often come with migration in search for a community.

Also read | Memory and Companionship in a Women’s Circle in Northeast Delhi

Under these circumstances, holding land and family documents become even more difficult for trans women. Baruah notes that returning to the birth family to collect documents and fulfil the demands of the NRC process forces many trans people back into abusive and hostile households and associated trauma. To many, going back to their birth families is not an option at all. Baruah estimates that nearly two thousand Assamese transpersons have been left out of the NRC, including those who have migrated and could be closeted. However, Baruah asserts that being a trans person is not the immediate cause of their exclusion. Perhaps Baruah’s own situation provides a telling contrast. Even though she has had to go through her own struggles of acceptance with family and society, Baruah’s family lives with her today. She also has documents that assert her family’s 200-year history and residence in Assam, and the privilege that comes with it. Most importantly, Baruah has the social capital of being a judge and an activist. For her, therefore, proving her relationship with land, family and the state was straightforward. These are luxuries that most trans persons from the state cannot afford.

Procedural inconsistencies within the NRC also add to the roadblocks. While registering as a trans person is possible in the first round of the NRC, trans persons against whom objections have been raised do not have the option to identify as trans in the hearing. This creates not only a problem of misgendering but also of potentially damning documentary inconsistencies.

Direct engagement with bureaucracy and police often subject trans persons to further vulnerabilities and potential abuse. These engagements, more often than not, force trans persons to argue for and defend their gender identity over and over again. Baruah says, ‘Rather than the person’s identity, they are interested to know what is between the legs… Even if you see the various police harassment cases with respect to the transgender community you will find that most of the trans persons are being sexually abused by the police… Most of the officials are still not properly sensitized or well versed with the transgender factor.’ As a result, many try to limit their direct engagement with the police and other arms of the State to the minimum. Many trans persons whose names did not appear in

the first NRC draft, therefore, did not even file claims, to avoid putting themselves through the hearing process.

Designing an inclusive citizenship requires the acceptance of the cultural and social realities of trans persons, looking beyond heteronormative imaginations of ‘family’. Baruah argues that the NRC process would therefore have to recognize the legitimacy of the adoptive family structures of gharanas, accepting the lineage of the guru–chela tradition.

We met Swati in November 2019.