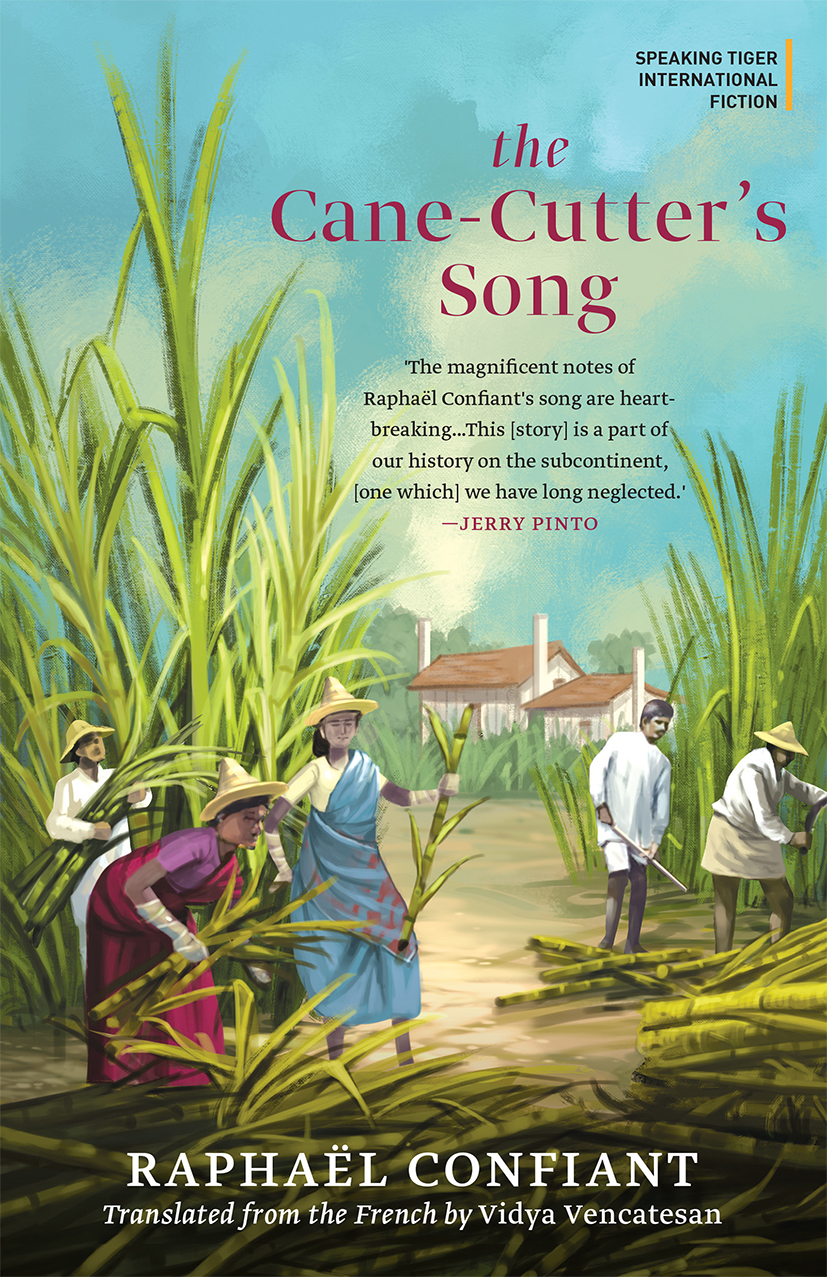

In The Cane-Cutter’s Song, originally published in French as La panse du chacal, award-winning Martinican author Raphaël Confiant illuminates the lesser known side of the West Indian identity—the Indian side of the Creole, and within it the story of thousands of lost Indians who longed to return home. Available for the first time in English, this impeccable translation by Vidya Vencatesan is an immersive and riveting read.

Below is an excerpt from the chapter “Goddess Mariamman and the Coromantee Negro” of the book.

Goddess Mariamman and the Coromantee Negro

Her hunger is never satiated; she does not stop demanding alms, more alms and still more alms. Sugarcane, o avatar of the monster Varahi! You have dragged us mercilessly from the cotton fields of Madras, from the paddy fields of Canton and from the forests of Congo, with false promises of happiness. You plunged us into a terrible torpor before crushing us; from now on, we will be the dregs of the earth. But in front of Mariamman, so beautiful and dressed in saffron, our Goddess without a face, you must admit defeat!

Everyone remembered Théophile Leroux’s arrival at Macouba. It was the year which followed the Catastrophe, what the Whites and the nouveau riche Mulattos called the Mount Pelée eruption at the turn of the century. Everyone at Hauteurs Courbaril had lost a family member, some a friend, some an acquaintance and the number of those charred to death took you totally aback and grieved you: thirty thousand people. How could such a large population manage to pile up in the cramped lanes of the city of Saint-Pierre? Vinesh had been there only once. Two or three months before the terrible event in March or April 1902. He did not remember it very well. When Béké de Maucourt refused to sign Adhiyaman’s letter of repatriation to India citing imaginary debts contracted at the plantation shop (May Kali the dark one, strike Man Ninise the shop owner, with her sword), Adhiyaman resolved to go to Saint-Pierre to claim his rights. He took his family there, making the most of the brief period of leave between the end of one cane harvest and the point when the cuttings were replanted, between the end of June and the middle of August. He already knew the place, having accompanied the steward, Marcel Polygone and the foreman Sosthène to pick up barrels of salted meat, crates of dried codfish and machetes ordered by the Courbaril Plantation. Adhiyaman thought that it looked like a replica of the port of Pondicherry: noisy wharves, crowded with goods coming from the whole universe where laughing gabariers, barge sailors, paced around; importexport shop assistants in detachable collars; femmes-matadors, coquettish and overbearing women, who sashayed about ravishingly, wearing dashing Creole dresses; gangs of idle youngsters looking to play a prank; sinister-looking swindlers; Indians adrift. The miserable fate of his compatriots in Saint-Pierre terrified him. Dressed in torn rags, drunk as old skunks, they wandered about the wharfs, trying to get hired on one of the innumerable ships flying so many different flags, which crowded the harbour. Most of them had fled hinterland plantations to end up in the infamous quarter of La Galère, the city’s garbage dump at the mouth of the River Roxelane. There—in the middle of gallows-bird Negroes, boorish White men who had recently arrived from Europe, their faces sown with scars that bore witness to their sinister feats, and toothless wily Chinese who ran illegal mahjong parlors—these Indians lived a hopeless existence. Some were but stumps of humanity, their bodies ravaged by smallpox or syphilis. With little or no knowledge of Creole, they could not communicate and had become the whipping boys of Négrillons, Negro pickneys, who guffawed at these Indians that staggered down the road. The Négrillons enjoyed throwing at them anything they could lay their hands on while shouting:

‘Coolie, you smell of piss! Coolie beggar! Coolie dog eaters!’

Other Indians, less flea-ridden but just as unfortunate, awaited their repatriation in a shack of the Le Mouillage quarter, called Coolie Warehouse. These had kept up a semblance of dignity even though they had to do unpaid work for the municipality. In return, at midday they were served the leftovers of the meals from the Bethlehem Home. Most of them worked for the cleansing department of the city as street sweepers or latrine bucket cleaners. When evening approached, mixed groups of women and men came into the city, at least into the rich quarters, hugging the stone walls of the White traders or bourgeois Mulattoes’ dwellings, their eyes always lowered because of the immense shame that choked them. They went in groups of six, two at a time, carrying a tank made of zinc in which the others quickly emptied the chamber pots from Aubagne. Once the tank was full to the brim, clenching their jaws in order to be able to bear the stink, they lifted it together and rushed to the banks of the Roxelane to empty it. This operation had to be repeated four or five times in the course of an evening depending on the number of chamber pots that had been set out by the inhabitants, some of whom had not put the pots out for several days at a stretch, out of negligence. These reeked like rotting carcasses and the foul smell permeated the Indian cleaners’ clothes; even sea water could not completely dissipate it. This gave a chance to the Creoles to invent a new term of abuse:

‘Shit smelling Coolie, dog!’

Suppressed anger choked Adhiyaman, especially as neither the steward, Polygone, nor the foreman Sosthène, busy with their business, seemed unaffected at this awful sight which was repeated everyday of their week in Saint-Pierre. Upon his return, thinking the boys were asleep, he told Devi:

‘It is a very beautiful city. There is even a theatre where people go all dressed up in a tramway that links the two ends of the city, but it is hell for the people of our race. Hell!’

However, he had decided to take his family there to try and clandestinely embark on some British ship, in charge of repatriating the many indentured labourers from the French islands and the British colonies. They sailed up the river Demerara in British Guyana, then berthed at Trinidad—the southernmost island of the entire archipelago—making short stops at Saint Vincent, Grenada and Saint Lucia before stopping at Saint-Pierre in Martinique. Adhiyaman had thought of contacting an interpreter on board to bribe him with the savings which he had put away over seven years and eight months of hard work at Courbaril Plantation. The operation was perilous, because if unfortunately, he were caught, he would be sent to jail and his wife and children would be dispersed across plantations on the Caribbean coast— plantations where the land was barren and unproductive, and work was back-breaking.