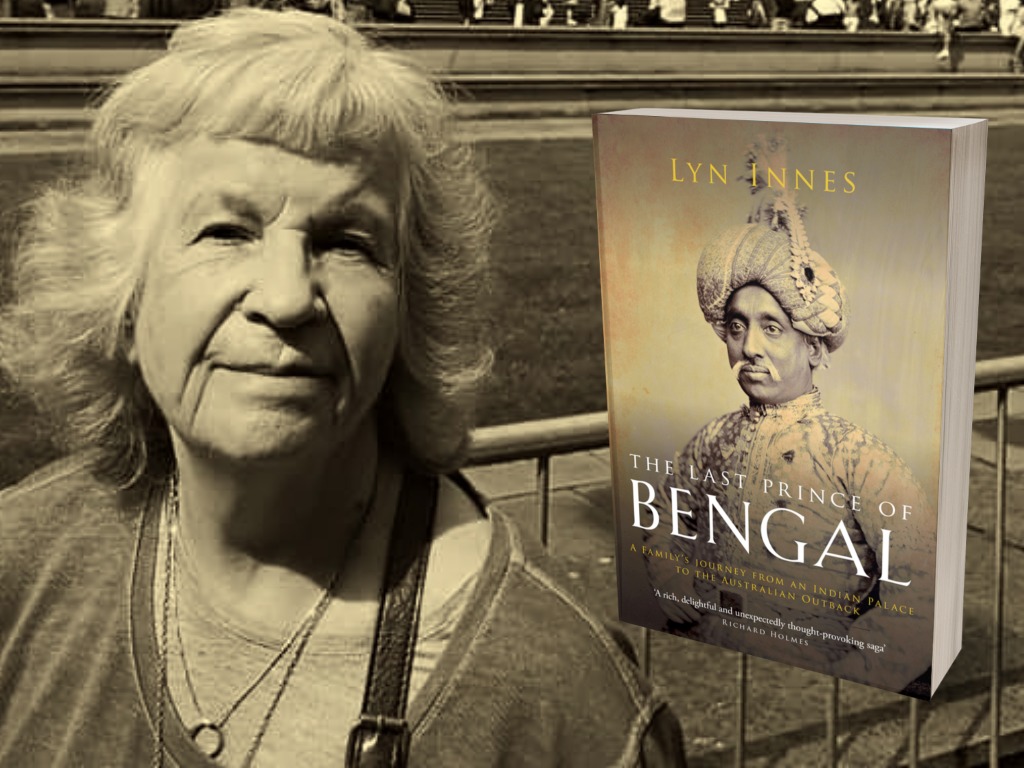

The Last Prince of Bengal is the intimate story of one family and their place in defining moments of recent Indian, British and Australian history. From glamourous receptions with Queen Victoria to a scandalous Muslim marriage with an English chambermaid; and from Bengal tiger hunts to sheep farming in the harsh Australian outback, the book visits the extremes of British rule in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, exposing complex prejudices regarding race, class and gender as Lyn Innes recounts her ancestors’ extraordinary journey from royalty to relative anonymity.

In this conversation with writer Githa Hariharan, Innes talks about her book, the complex web of women’s stories therein and more.

Githa Hariharan (GH): Though the figure of the “last prince of Bengal” holds a travelling narrative together, there is another strong story thread across continents. This is the story thread of women – of those who remain, or are pushed back, into circumscribed spaces; and of those who aspire to a different identity, and succeed, or almost. Would you talk about this complex web of women’s stories in the book?

Lyn Innes (LI): One of the difficulties I had in writing the book was my awareness of the many hidden stories of women, stories that I was unable to uncover and only hint at.

There is the story of the Nawab’s most beloved wife, Hasina, who had been his mother’s African slave. That also suggested many other stories which nobody writes about, concerning women brought from North Africa to India and sold to wealthy Indian households.

And then there are the other nikah and mutah wives, some twenty-six in all, with whom the Nawab had over 100 children. Their stories are also unknown to me, although had my Urdu and Persian been better, I might have been able to uncover some of them.

When the Nawab came to England there was almost daily coverage of him in the newspapers as well as sketches and pictures, but nowhere during the 10-year marriage is there any mention of his wife Sarah, my great grandmother. No were there any photographs. She never accompanied him on formal occasions, as there is no mention of her among guest lists. It was only after the Nawab died and she began to fight for custody of her children that her name appeared in the newspapers, and I was able to catch glimpses of her character and courage.

Also read | Excerpts from The Last Prince of Bengal

At that time, it would be possible for her to gain custody if she could claim that her marriage was illegitimate, which would also have meant that she would lose her status as a respectable married woman, and also any claim to a pension from the Nawab’s estate. Nevertheless she did argue the marriage was illegitimate, and staked everything on trying to get to back her children. Ironically the court disagreed, saying that her marriage was a legitimate Muslim marriage, although the British government refused to give her the mahr of £10,000 the Nawab had promised when they were married. And so, like Cinderella, she disappears from sight once she marries the Prince and must await his disappearance before she can reappear. Nevertheless her marriage did allow her to escape poverty and the daily grind of hard work.

As with Sarah, my grandmother Elsie’s marriage to Nusrat, Sarah’s youngest son by the Nawab, meant a big jump in terms of class from governess to princess. It was a status she reveled in and which helped her gain notice as a writer. It also allowed her to rewrite her life in several ways at several different times.

GH: You are the historian and storyteller here – of the mingling of race, class, languages. How do you see yourself as a part of the story, its past and the identity/ identities you give yourself in the present? What did it feel like researching your own family?

LI: I grew up when Australia’s white Australia immigration policy was still in force and Indians were not supposed to be in Australia. As a result my mother rarely spoke about her Indian heritage and discouraged us from talking about it. So to begin with the sense of an Indian background was there but it was also a secret, a slightly scandalous one.

Later I became aware that my grandmother called herself a princess and the idea of a royal connection did not displease me as a teenager. After I left Australia and became involved in radical politics, I began to embrace my Indian heritage and rather wish that royalty was not involved. So these were ambivalent feelings when I first began to research my family history and realise it was connected intimately to the beginnings of the British occupation of India. I remember giving a talk a few years ago where a young Bengali asked me how it felt to be descended from Mir Jafar? I replied that I felt neither pride nor shame, but nevertheless did feel it gave me a connection to India and to India’s history, and for that I was glad. Moreover, it gave me a sense of belonging to a wider world than Australia, or England or even Europe. And researching the history of the family brought a clearer understanding of the ways in which being subjected to British rule affected individual lives in India and created divided and ambivalent loyalties. Above all, I suppose it has led me to reject the notion of simple identities, to realise the absurdity of racial categories, and to embrace the sense of a complex and often contradictory identity. I am privileged, but not because of a royal ancestry, I am Australian, but not the Australian most people envision, I am white and not-white, and I am Indian and not-Indian.