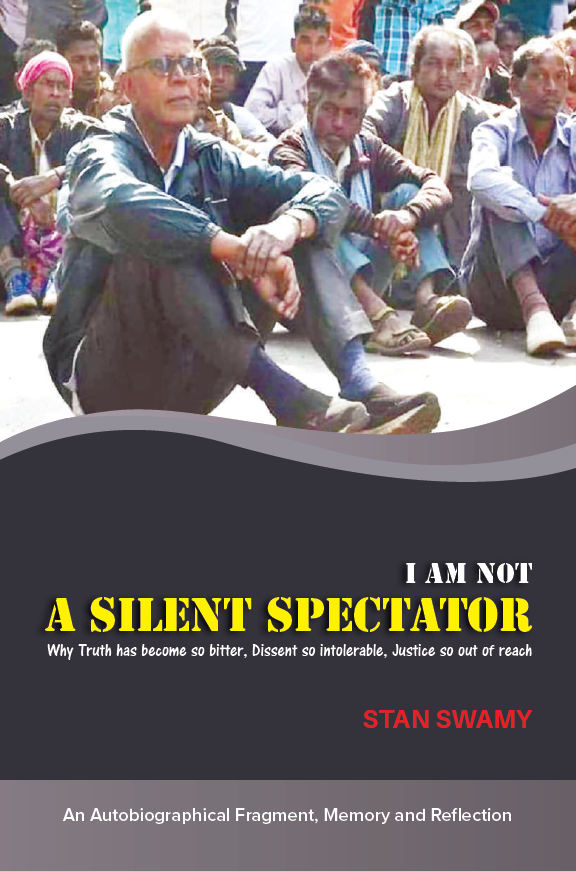

“A tall thin man with a spine of steel” writes Nandini Sundar, describing her friend Stan Swamy in the Introduction to Stan Swamy’s I am Not a Silent Spectator: Why Truth has become so bitter, Dissent so intolerable, Justice so out of reach. Today marks a month since his death as a pretrial prisoner, after enduring months of abuse from the NIA and jail authorities who withheld the smallest of comforts from him. Swamy was never interrogated by the NIA during nine months of incarceration. Repeatedly denied bail by the courts, he also suffered from medical neglect and in May contracted covid at the Taloja jail. That Swamy was a national treasure and his death a political murder is affirmed with every passing day. Sundar speaks of him as a living person – which is piercing but also comforting, for Swamy writes in the Epilogue that he wishes to be remembered in the way departed spirits are by adivasi communities, always present beside them in their political struggle and resistance.

Published by the Indian Social Institute, Bangalore – where Swamy was Director from 1975 to 1986 – this volume sets before us the clear-eyed sociologist and activist for adivasi rights. It reclaims his life work from his tormentors – ideologues of hindutva and neoliberalism, politicians, state functionaries and figures in mass media. Swamy and they change places now, for good; he begins to loom large as they recede into footnotes of infamy.

Repressed but not defeated: The sad saga of ‘under-trial prisoners’ and unfinished efforts to reach out to them

When one opens the morning newspaper or opens a TV news channel in the Adivasi states of Central-Eastern India, one finds the media reports of one or more Adivasi and Dalit youth being sent to jail on the suspicion of being naxals or helpers/sympathizers of Naxals. According to media reports, several hundreds of Adivasi and Dalit youth are languishing in the jails of Jharkhand as naxal-suspects. When the general reading/viewing public gets used to this as a matter of daily occurrence and finds nothing amiss, it is a dangerous sign for a healthy democracy. Sadly, most of the educated, urban, middle-class public approves of this police action and is happy thinking that the police are doing a ‘good job’ against what is called “Naxalite-menace”.

According to media reports, several hundreds of Adivasi and Dalit youth are languishing in the jails of Jharkhand as naxal-suspects.

In 2015, we at Bagaicha, felt that we should not rest with the media reports but should find out the reality ourselves. First, we approached jail-superintendents for permission to go inside the jails to interview the UTPs but our request was flatly refused; then we sent a questionnaire as per the Right to Information Act (RTI) to all jail-superintendents of all the 24 jails of Jharkhand. As per the Act, the respondent must answer the request for information within 30 days of receipt of the application. We patiently waited for two months and only 12 of the 24 jail superintendents bothered to respond; and that too, haphazardly. We, then, complained to the Inspector General of Prisons. However, he too washed his hands of the responsibility, saying that he was new to the job, did not know the precedents, and hence, could not act on our complaint. The Bagaicha Research Team, then, decided to do a sociological sample study of Under-Trial Prisoners (UTPs) who were out of jail on bail but who still run to the courts for every date of hearing where no trial-hearing takes place but instead they only get the next date!

The research team consisted of Bagaicha staff and some UTPs. The sample study took six months to complete. The Team met 102 UTPs in their own homes in 18 of Jharkhand’s 24 districts. The Research Report was published in October 2016 under the title: ‘Deprived of their rights over natural resources, the impoverished Adivasis find prison’. The study brought to light some startling facts: (1) Of the 102 persons interviewed; only three admitted that they had any relation with any naxal/Maoist groups. That means, 97 per cent of those jailed as naxal-suspects are likely to be innocent. Can there be a greater injustice done to the hapless Adivasis/Dalits? (2) The proportion of Adivasis and Dalits to those of general categories was far higher than that found in the general population; (3) Most of them were picked up by the police either from their homes or from buses/trains on the way to the market/town, thus disproving the police version that they were captured in the forests as they were trying to flee; (4) Two-thirds of them were in the age-group of 18-35, just the age when a young man becomes an active member of the community, settles down in life, marries with his wife and has small children, and most of all is the sole or main breadwinner of the family. By being suddenly plucked away and thrown into jail, the whole family is irreparably affected, and often their small assets of land/cattle either sold or mortgaged. In short, several families have been reduced to destitution; (5) Most of them did not even know why they were arrested until charge sheets were filed and they saw to their horror that they were implicated in too many legal clauses; and it would take years before they can come out clean from all the litigations. In other words, their family lives have been ruined permanently; (6) ‘Bail is a right of the prisoner’, but who will bail them out? Even if the court grants bail, one has to look for ‘bailers’ and lawyers to pursue the case; all this costs several thousand rupees which is far above their capacity. Hence, most of them, their families and communities, have been suffering in silence. Their small children grow up without paternal love and care.

If there is strong resistance against land alienation and consequent displacement, the ‘law of eminent domain’ of the state would be liberally used.

The Bagaicha Research Team felt that having found out the truth, we had to act on it. The only way of doing this was to take recourse to legal action. After consulting several legal professionals, a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) was filed in the Jharkhand High Court towards the end of 2017. The PIL got admitted in January 2018, with Stan Swamy listed as the main petitioner. The Chief Justice, even as he admitted the case, directed the state to furnish all the required information about all the UTPs in Jharkhand. It is now one-and-a-half years and Jharkhand state is yet to submit the complete details of all the prisoners. All kinds of excuses have been proffered before the court. Some eminent lawyers have offered to argue the case. However, the case has not come to the argumentation stage yet, since we do not have all the required information about all the UTPs of Jharkhand.

Our prayer before the HC is: (1) that all UTPs in Jharkhand jails be released on personal bond since they cannot afford regular bond; (2) that their trial-process be speeded up with the certainty that most of them will be acquitted; (3) that a judicial commission be appointed to find out and rectify the inordinate delay leading to so much human suffering and denial of their human and constitutional rights; (4) that the police officers who deliberately and illegally arrested them be given exemplary punishment; (5) that a just and adequate compensation be paid to the families of those acquitted. We have been hoping against hope that justice will be done to the unjustly imprisoned Under-Trials.

We feel that this PIL, of which I am the main Petitioner, has become a thorn in the flesh of the state government since it takes to task the state for its deliberate persecution of Adivasis and Dalits. The state, in this case, has much to hide. Hence, the Jharkhand police, in connivance with the Pune police, are trying to get me out of the way by implicating me in a faraway Bhima-Koregaon case. Additional reasons for such implication will be detailed in the following pages.

The real purpose is to irreparably maim Adivasi and Dalit communities by incapacitating the younger generation. Even if they manage to get bail, they would be running to the courts for years. They would have spent their limited resources and would be forced to move out of their homes/villages/communities just to eke out a living as casual/ contract labourers. Their small children will be growing up without paternal love and care. Their strong community-bond and their community-based culture will dissipate. The onslaught on their land, forest, despite so-called ‘protective laws’, would continue unabated all in the name of ‘national development’. If there is strong resistance against land alienation and consequent displacement, the ‘law of eminent domain’ of the state would be liberally used. It is a well laid out plan to extinguish the Adivasi (indigenous) and Dalit peoples as distinct social groups asserting their special constitutional and human rights.

It is, hence, all the more important that this case, on behalf of the thousands of Under-Trial Prisoners, be fought till justice is done. Some eminent lawyers have offered to argue the case in Jharkhand High Court when it comes to the argument-stage. But the state is doing all it can to see that it does not reach that stage.

It’s a long road to freedom!