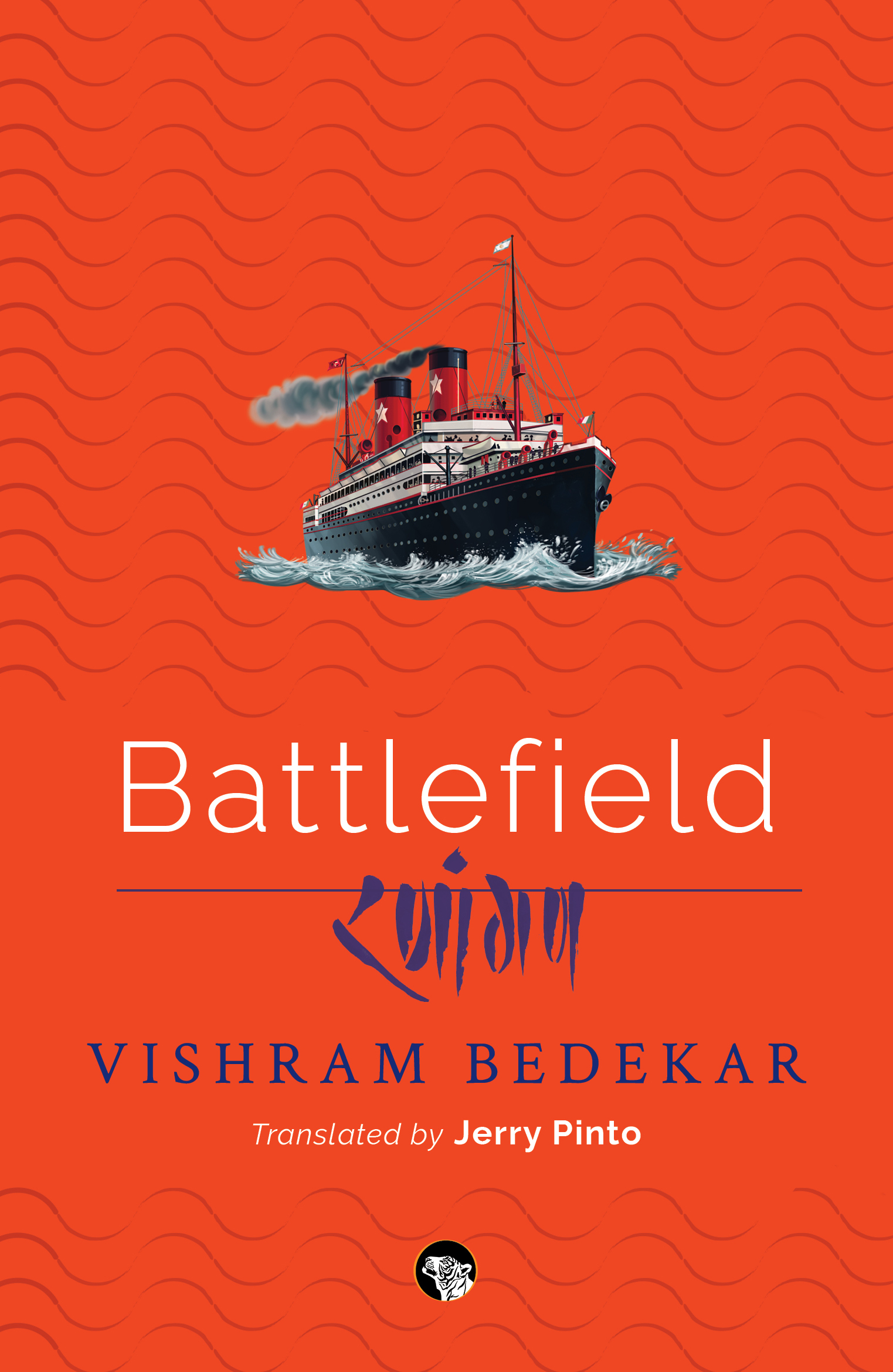

Vishram Bedekar’s novel, Battlefield, published in Marathi as Ranaangan (1939) and now translated by Jerry Pinto, is the story of a shipboard romance between an Indian man and a German-Jewish woman, both fleeing Europe before the Second World War.

Chakradhar Vidhwans is on his way back to India after a long sojourn in England. The ship he boards at Genoa, in Mussolini’s Italy, is en route to Shanghai and among the passengers he meets is Herta, fleeing Germany for the Far East. Chakradhar and Herta are powerless figures, the castaways of a racist and imperialist world now on the brink of war. It has forced her out of her home and him to return to his. As the two get to know each other they fall in love and, briefly, for the duration of the voyage, it begins to seem they may yet salvage some grace from their circumstances. But the world that threw them together also forces them apart. The great tragedy about to unfold globally will not spare them.

Together we left the smoking room.

There were writing tables outside. Two young women were writing letters. By the wall, deck chairs in which a couple of travellers were taking naps. Behind, a ladder. On the left, two large windows. No, French windows. Around us, the Mediterranean Sea. As the ship cut through the water, sprays rose, decked with foam. A fine mist settled over us. Next to the railing sat a young woman in thin soiled clothes. Her hair was dishevelled and her general appearance spoke of her poverty. A child was trying to climb the rails. His exasperated mother tried to keep him from getting too high up.

Shinde called, ‘Louis,’ but the boy did not turn around. Meanwhile, I was trying to keep my balance as the waves rose and fell, forming hillocks and then collapsing into troughs. You could feel you were on a swing if you watched them too long and here was a little boy, monkeying about on the rails. Louis’s mother saw Shinde and smiled a welcome. She pulled at her son’s clothes: ‘Louis, ihr “uncle”.’

Louis was not paying attention but he turned at the word uncle. He had a sweet face but it was clear from his expression that he did not want to talk to this uncle.

‘Nein, nein,’ he said now. ‘Deutsch?’ Shinde turned to look at me.

‘See? He doesn’t want an English uncle. He wants a German uncle.’

And then he reached over and picked the child up. Louis seemed to like Shinde. He gave him a couple of friendly slaps on the cheek and then nipped him too. He said, ‘Onkel, onkel.’

Shinde, and Louis and I played for an hour. We did not understand what he was saying any more than he understood us. He didn’t like English and we had no German.

This barrier only added to the fun. Each time we managed to communicate in gestures and mime, we rejoiced. And each time we failed, we laughed even more loudly. We were all travellers from different lands to different destinations but a child had made children of us all. We didn’t talk about the war or other darksome topics. There was no prejudice, no bias in our laughter. We did not insist on this or that nor did we argue and we felt no fatigue. This seemed to spread to the others on the deck and by the railing, as they watched two grown men cavort with a little boy. The memory of those moments brings a pang. And then I wonder whether memory is a blessing or a curse.

By evening, we were both very fond of the boy. Nor would he let us go. It was close to dinner time and I had to change my clothes. I picked Louis up, set him on my hip and went on the deck. Everyone we met along the way stopped to speak to me. The women, who would otherwise ignore us and walk past as if blinkered, now stopped and smiled. Even the Anglo-Indian girl who hated the sight of our brown faces could not resist. We met Marthe who tried to take Louis. She pinched his cheeks gently, tickled him a little and tried every trick in the book but when she tried to pull him away, he simply refused to let go of my neck. Finally Shinde took him from me and I straightened my tie, which had been set askew by our rough-housing. Suddenly someone placed a hand on my shoulder. It was Madnani. He squeezed my arm and said, ‘That’s the stuff. You catch the child; the child catches the lovelies for you.’

I was a bit sickened but I decided to let it pass. Shinde was speaking to Louis’ mother. She looked happy, the poor thing. The chief steward was close at hand. He was adjusting his bow tie. He winked at me.

‘What is it?’ I asked.

He came forward. Shinde was talking to Louis. He tickled Louis now and said, ‘Good boy. Better Mummy. Clever fellows, you two.’

Shinde went red. He shook his clenched fist in the steward’s face. ‘Do not say that again or you’ll get a taste of this.’

Louis’s mother had missed this interchange. She continued smiling as if unaware of the undercurrents.