Ghazala Wahab’s Born a Muslim: Some Truths About Islam in India tracks the history of the religion from its revelation in Arabia in the seventh century to its spread through many parts of the world. Weaving together personal memoir, history, reportage, scholarship, and interviews with a wide variety of people, Wahab highlights how an apathetic and sometimes hostile government attitude and prejudice at all levels of society have contributed to Muslim vulnerability and insecurity.

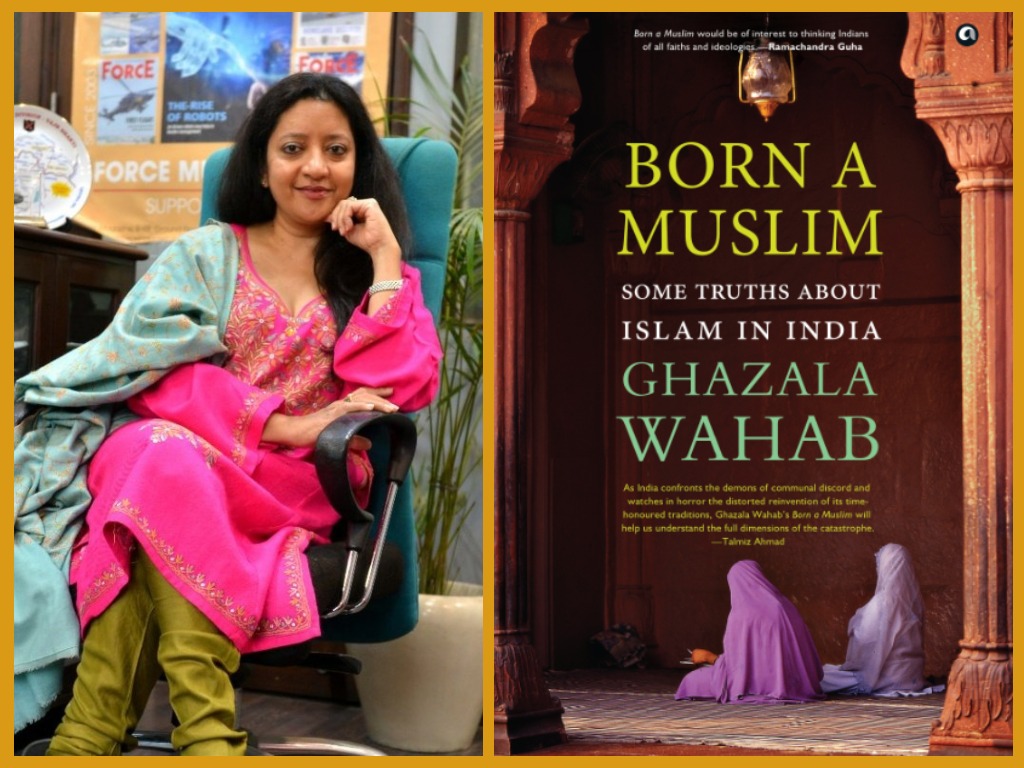

In this conversation with independent researcher, writer and women’s rights activist Sahba Husain, Ghazala Wahab talks about her book and being ‘born a Muslim’.

Sahba Husain (SH): I read your book with keen interest. As a fellow ‘born Muslim’ growing up in Hyderabad, Born a Muslim had a certain resonance for me, particularly in the Introduction where you reminisce about your growing up in Agra, recalling both celebratory — Ramzan and Eid — as well as terrifying moments and events in your family/community that was gripped by violence and fear. How far did these specific experiences shape your Muslim consciousness/identity?

Ghazala Wahab (GW): I was always conscious of my Muslim identity, despite my family’s nearly nebulous relationship with the religion. It had partly to do with the fact that we never felt the reason to underplay it and partly because of where we lived. The mosque was next door, divided by a barely-there lane. A muezzin’s call was part of our daily lives. The most remarkable part of my upbringing was that even if my family felt insecure in their Muslimness sometimes, it didn’t let that insecurity percolate down to the children. So, I, like my siblings, cousins included, grew up without any identity markers or consciousness. I didn’t hold the communal experience, when it happened, as a consequence of my Muslimness. My understanding was different from my parents not only because of the generational gap, but experiential gap as well. Furthermore, as I studied and worked with people from all communities, who did not make a big deal of religion, my identity always remained on the periphery of my existence. Perhaps, that explains why I had a bit of a condescending attitude towards Muslims. My privileges clouded my vision.

As I studied and worked with people from all communities, who did not make a big deal of religion, my identity always remained on the periphery of my existence.

SH: You wrote in the Introduction to the book, “as a child, Islam came to me gently…” Could you elaborate on this further?

GW: As I have written in the book, unlike most Muslim children, I did not have a formal or structured introduction to religion. I had barely started to speak when I was taught to memorise the first Kalima. I was told to recite it first thing when I wake up and the last thing before sleeping. Or at any time I was afraid. This is a habit that has stayed with me. That was all as far as formal introduction to religion went. You may know that most Muslim households initiate their children very formally into Islam. From the time you begin your reading of the Quran through Qaeda or when you keep roza for the first time during Ramzan. Or when you finish your first reading of the Quran. All of these are marked as milestones in a child’s life. I did not have that. I read the Quran in my adulthood through a hafiz that I employed. When I speak of ‘gently’, this is what I mean. Similarly, the meaning of several Quranic verses was paraphrased over the years and told to us so we understood what good behaviour was expected of us and what being a good Muslim as well as a human being meant.

Forget bigots, even many ordinary people refuse to question the stereotype that was peddled to them as truth. This is pushing Muslims further towards the margins of the society.

SH: You mentioned that despite shedding their ghettoised Muslim identity, your father and uncle were nothing but Muslims when it came to communalisation — “forever suspects, forever scapegoats”. Do you see this as a larger reality for Muslims in India?

GW: Yes, it’s an unfortunate reality. What started as a mistrust of Muslims after the Partition has blown up into unabashed hatred. A consequence of this is that, forget bigots, even many ordinary people refuse to question the stereotype that was peddled to them as truth. This is pushing Muslims further towards the margins of the society; perhaps some are already outside the margins. The most worrisome aspect of this sustained hate campaign is that Muslims are being dehumanised. However, I believe that dehumanisation is a two-way process. It affects both, the dehumanised and the dehumaniser. This journey that we have embarked upon as a nation, cannot take us to any place pleasant.

Also Read | Fear Within, Violence Outside

SH: Do you believe that the timing of your book is significant? Can it counter the deliberate vilification and hostility against Muslims and their vulnerability and insecurity? Did you have a target audience in mind while writing the book?

GW: It will be presumptuous of me to say that my book will make a difference; though it is indeed my fervent hope. Every book finds its time, and perhaps, this is the time for Born a Muslim. As I have mentioned in my introduction, I am addressing both Muslims and non-Muslims. So, all Indians, irrespective of their religion are my readers. I hope people outside India also find something worthwhile in it. The fact is that I am not just raising questions about Muslim existence in India, but about Islam’s existence in a Muslim’s life. This should have resonance among readers across nationalities.

The fact that some Muslims feel compelled to either assert or hide their identity is a sad reflection of our times.

SH: You wrote in the book that on the one hand, there is an attempt among Muslims to express their identity aggressively, on the other, there is also the felt need to hide one’s religious identity, as you found with workers during the course of shifting your house. Could you tell us more about this?

GW: Most Muslims in India lead dual existence—one among Muslims and another among non-Muslims. Both assertion and hiding of identity is a consequence of this. In both cases, it stems from insecurity. A self-assured person feels neither the need to assert her identity nor hide it. The fact that some Muslims feel compelled to either assert or hide their identity is a sad reflection of our times, which has robbed a Muslim of the social space in which she can be herself without constantly watching over her back.

SH: In what ways has the research and writing of this book impacted you? Has it led to a fresh understanding of Islam and Muslims in India?

GW: Yes, research for the book has been a learning experience. As I mentioned earlier, when I conceptualised the book, I did so from the place of privilege and presumptions. However, even then I was clear that I will be honest about both my knowledge and ignorance. Hence, when I began work on the book–both search and research– I had no hesitation in accepting my ignorance and junking my presumptions. Despite all this, what I was extremely pleased with, was my childhood understanding of Islam. What came to me in driblets is what I hold dear even today, which is why I tell my fellow Muslims not to junk their family heritage of Islamic practice, just because an ulema tells you that you have been doing it wrong all these years. Don’t let Islam be reduced to a list of do’s and don’ts. Let it be an experience that engulfs you without guilt or judgement.

By remaining in the mainstream, [Muslims] can ensure that only they remain the tellers of their stories instead of becoming invisible.

SH: Given the political climate in India today where Muslims are being further marginalised and targeted, what do you think is the way forward for them?

GW: The way forward is extremely difficult, yet predictable. The more Muslims are being pushed out of the mainstream; the harder they must try to remain there. By remaining in the mainstream, by drawing attention to themselves, they can ensure that only they remain the tellers of their stories instead of becoming invisible. I know this is easier said than done. But to my mind this is only way of fighting the wave of disinformation against them, fighting prejudice, stereotypes and hatred. It is extremely reassuring and inspiring that so many young Muslims, women and men, have been able to overcome the insecurities instilled by their parents to claim their space in India. They are role models for the community.

SH: One of the problems is the perception of a unified and homogenous Muslim community and identity. How does your research/writing and the ideas for the way forward help break this? Does the responsibility for breaking this lies with the Muslims?

GW: It does not matter where the responsibility lies. Each of us have to do our bit. The good news is, there is a growing community of non-Muslims which wants to work towards debunking stereotypes about Muslims. We need to engage with them. Dispel their misgivings. Help them overcome their uncertainties. The truth is, as Indians, the process of building a just, equitable and tolerant society is everyone’s responsibility.