A new survey of religion across India found that even as a majority of Indians believe that they are able to practice their religion freely, segregation runs deep as religious communities find little in common with one another, and friendships, marriages and other social bonds are overwhelmingly limited to their own religious communities.

Additionally, the survey finds that Hindu BJP voters who link national identity with religion and language and are more inclined to support a religiously segregated India, are also more likely than other Hindu voters to express positive opinions about India’s religious diversity.

This finding suggests that for many Hindus, there is no contradiction between valuing religious diversity (at least in principle) and feeling that Hindus are somehow more authentically Indian than fellow citizens who follow other religions.

Conducted by the Pew Research Center, the survey is based on nearly 30,000 face-to-face interviews between late 2019 and early 2020 (before the covid-19 pandemic). The survey was conducted in 17 languages, and researchers spoke to people who identify as Hindus, Jains, Sikhs, Muslims, Buddhists and Christians.

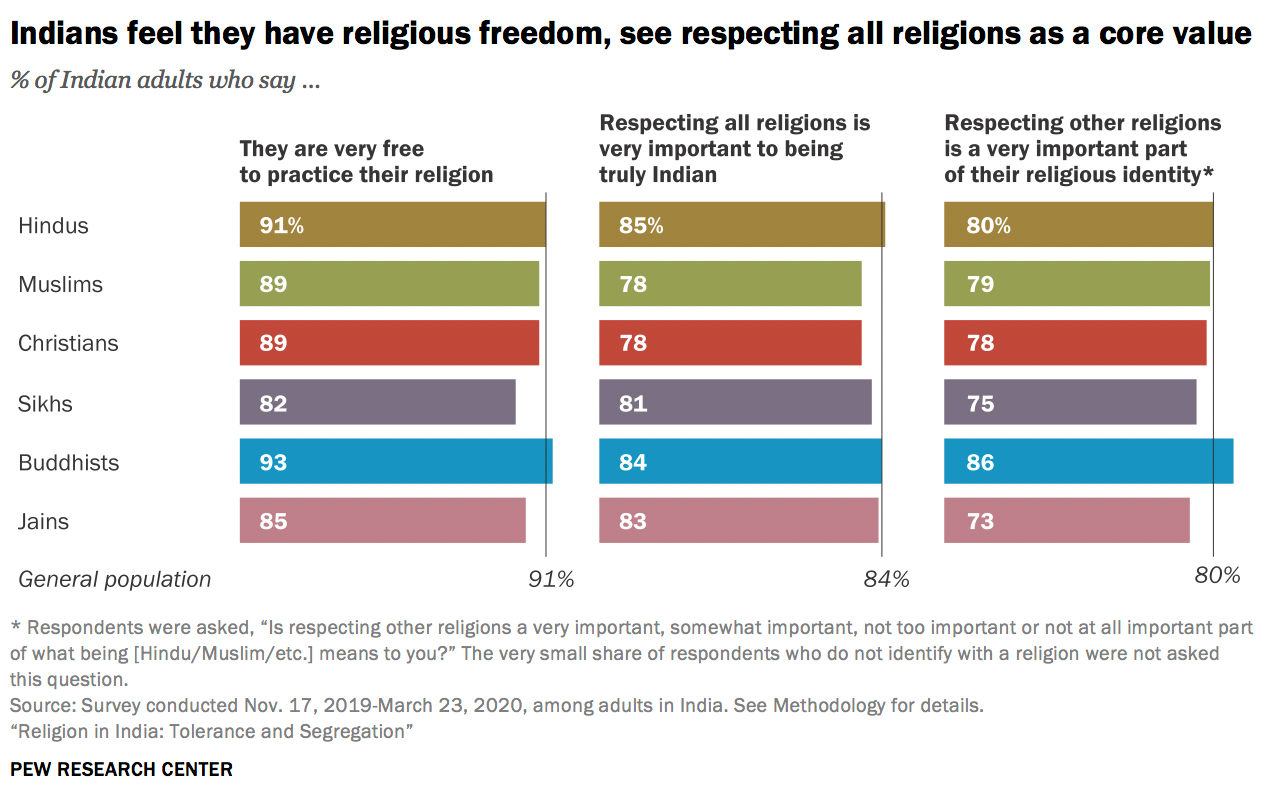

Indians, the survey found, overwhelmingly say they are very free to practice their faiths.

“Indians see religious tolerance as a central part of who they are as a nation. Across the major religious groups, most people say it is very important to respect all religions to be “truly Indian.” And tolerance is a religious as well as civic value: Indians are united in the view that respecting other religions is a very important part of what it means to be a member of their own religious community,” the report states.

The report notes that shared beliefs exist amongst communities. “These shared values are accompanied by a number of beliefs that cross religious lines. Not only do a majority of Hindus in India (77%) believe in karma, but an identical percentage of Muslims do, too. A third of Christians in India (32%) – together with 81% of Hindus – say they believe in the purifying power of the Ganges River, a central belief in Hinduism. In Northern India, 12% of Hindus and 10% of Sikhs, along with 37% of Muslims, identity with Sufism, a mystical tradition most closely associated with Islam. And the vast majority of Indians of all major religious backgrounds say that respecting elders is very important to their faith,” the report notes.

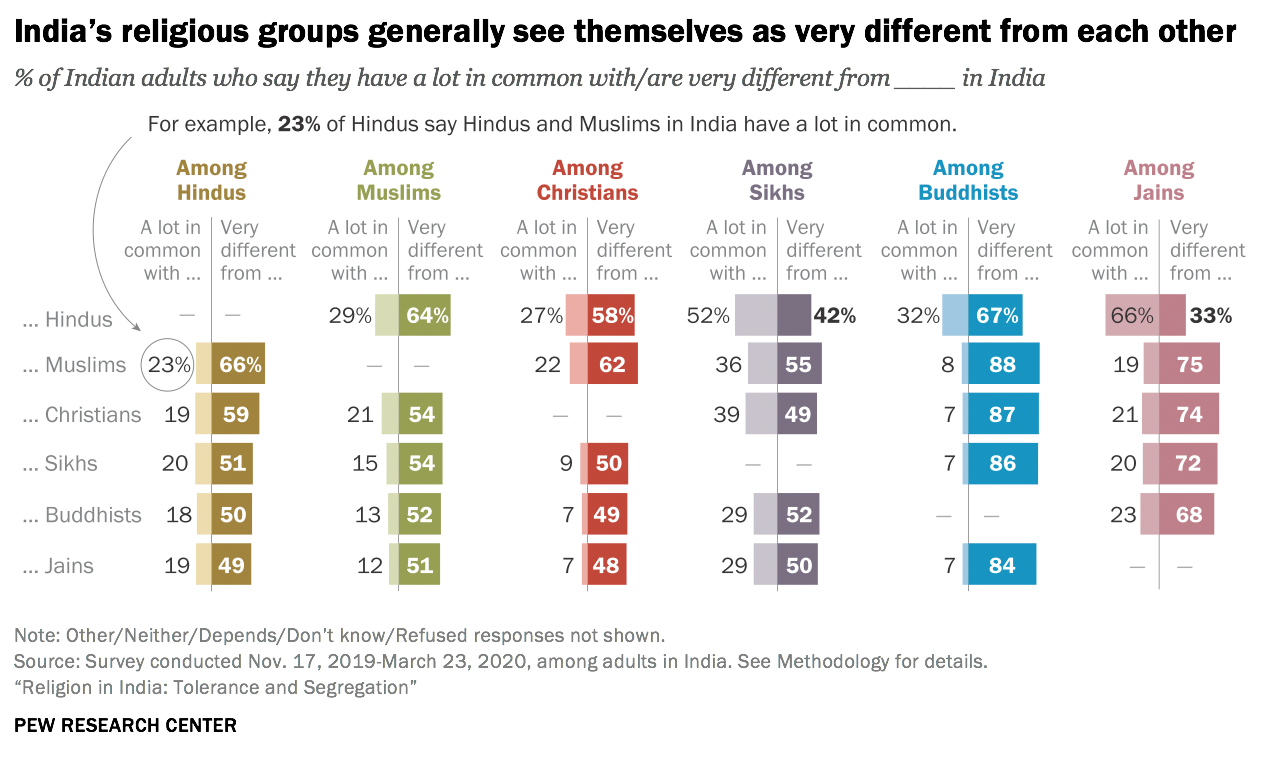

However — despite these shared values and the larger belief that religious tolerance is integral to India’s identity — segregation runs deep. “Yet, despite sharing certain values and religious beliefs – as well as living in the same country, under the same constitution – members of India’s major religious communities often don’t feel they have much in common with one another,” the report states.

The majority of Hindus see themselves as very different from Muslims (66%), and most Muslims return the sentiment, saying they are very different from Hindus (64%).

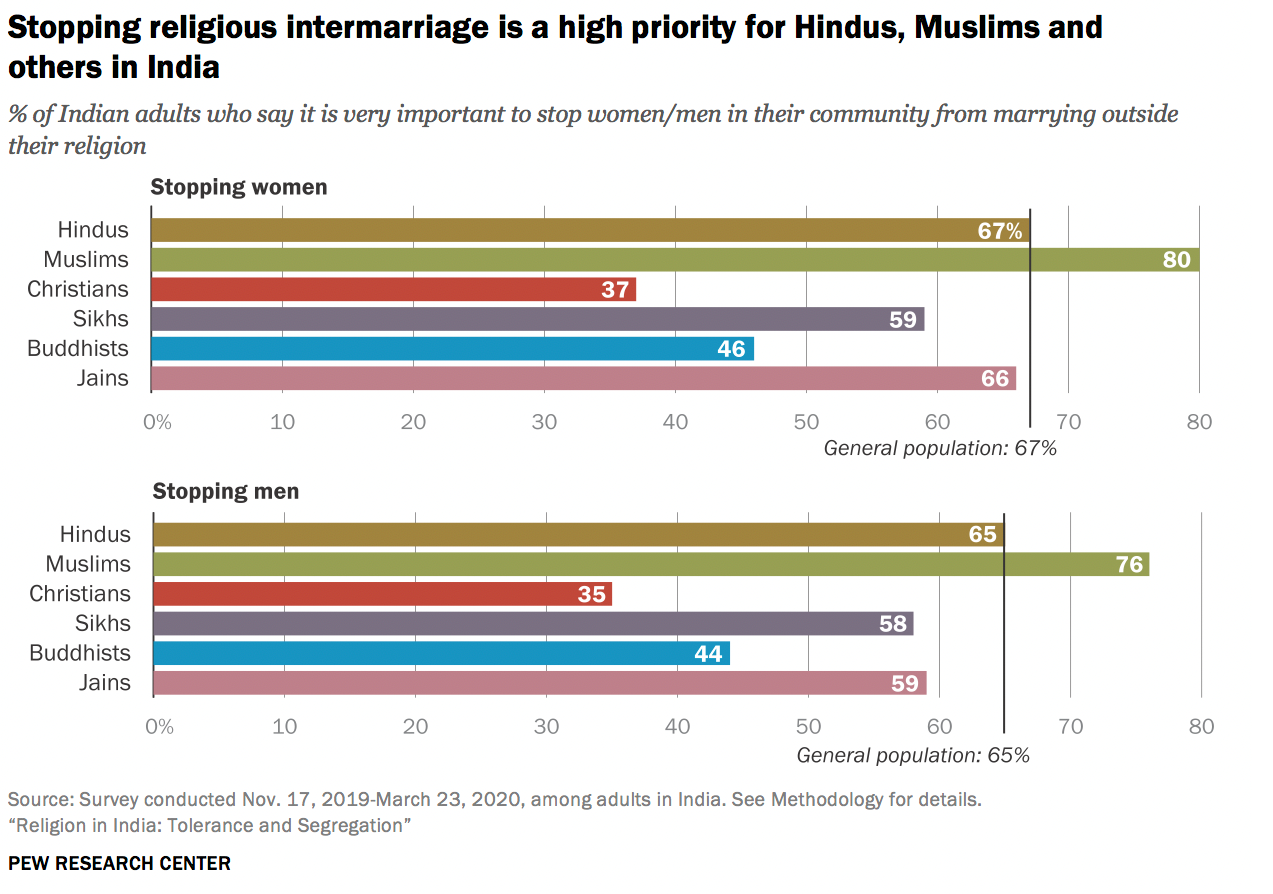

Additionally, social bonds are confined to one’s religious community. Roughly two-thirds of Hindus in India want to prevent interreligious marriages of Hindu women (67%) or Hindu men (65%). Even larger shares of Muslims feel similarly: 80% say it is very important to stop Muslim women from marrying outside their religion, and 76% say it is very important to stop Muslim men from doing so.

Friendships are also limited to within the communities. A large majority (86% of Indians overall, 86% of Hindus, 88% of Muslims, 80% of Sikhs, and 72% of Jains) say their close friends come mainly or entirely from their own religious community.

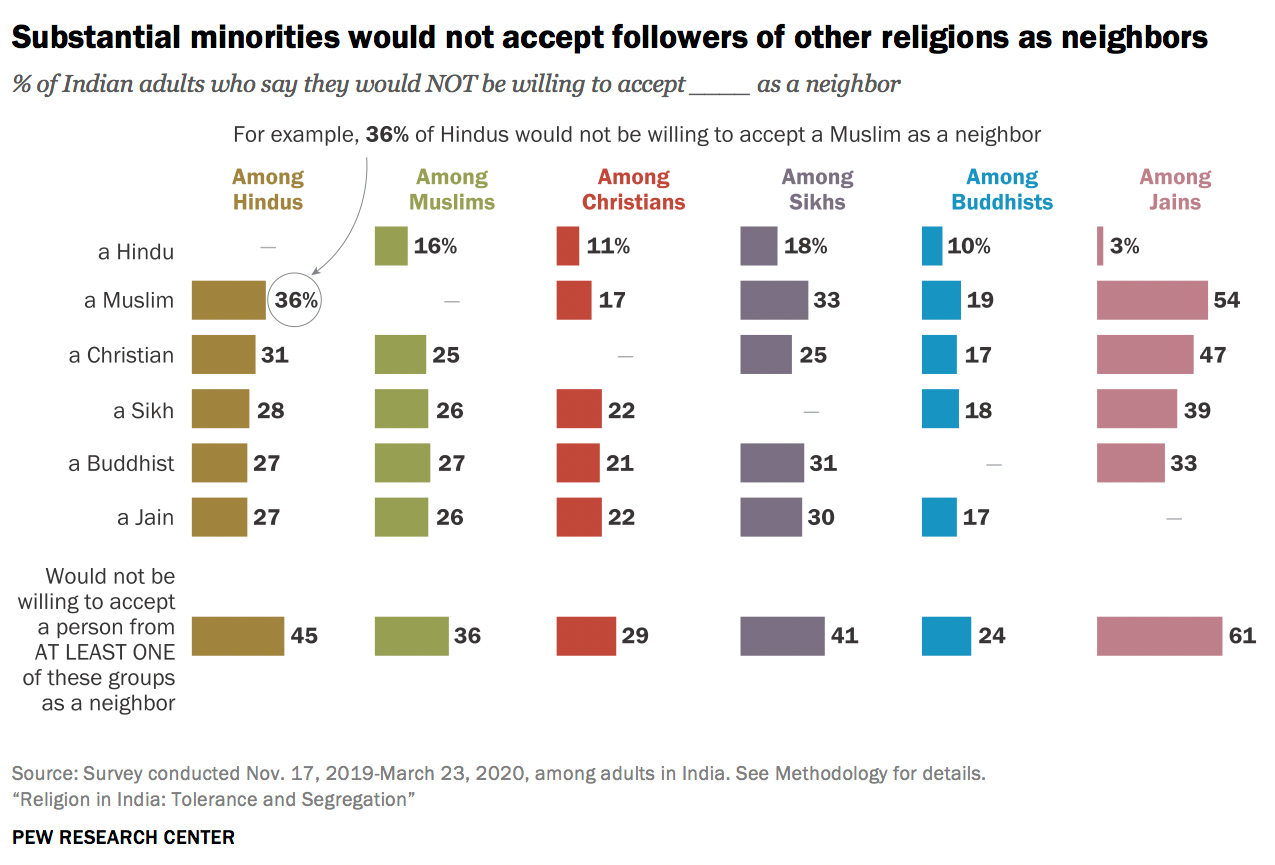

The report finds that a substantial number of Indians would in fact prefer to not have neighbours of another religion. While many Hindus (45%) say they are fine with having neighbours of all other religions – be they Muslim, Christian, Sikh, Buddhist or Jain – an identical share (45%) say they would not be willing to accept followers of at least one of these groups, including more than one-in-three Hindus (36%) who do not want a Muslim as a neighbour. Among Jains, a majority (61%) say they are unwilling to have neighbours from at least one of these groups, including 54% who would not accept a Muslim neighbour, although nearly all Jains (92%) say they would be willing to accept a Hindu neighbour.

“Indians, then, simultaneously express enthusiasm for religious tolerance and a consistent preference for keeping their religious communities in segregated spheres – they live together separately. These two sentiments may seem paradoxical, but for many Indians they are not,” the report says.

“Indeed, many take both positions, saying it is important to be tolerant of others and expressing a desire to limit personal connections across religious lines. Indians who favour a religiously segregated society also overwhelmingly emphasize religious tolerance as a core value,” it adds.

For example, among Hindus who say it is very important to stop the interreligious marriage of Hindu women, 82% also say that respecting other religions is very important to what it means to be Hindu. This figure is nearly identical to the 85% who strongly value religious tolerance among those who are not at all concerned with stopping interreligious marriage.

The report says that “Indians’ concept of religious tolerance does not necessarily involve the mixing of religious communities. While people in some countries may aspire to create a “melting pot” of different religious identities, many Indians seem to prefer a country more like a patchwork fabric, with clear lines between groups.”

The survey attempts to analyse what these religious fault lines mean for public life, especially as the relationship between India’s Hindu majority and the country’s smaller religious communities has acquired new relevance with the BJP in power at the centre.

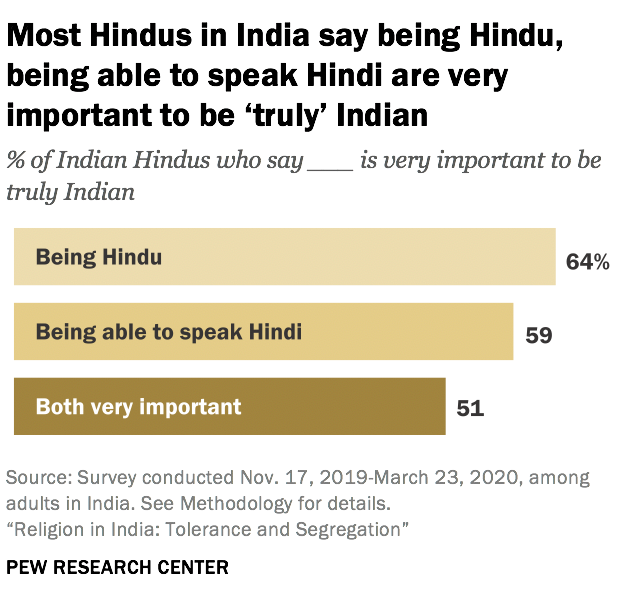

The survey finds that Hindus tend to see their religious identity and Indian national identity as closely intertwined: Nearly two-thirds of Hindus (64%) say it is very important to be Hindu to be “truly” Indian.

Interestingly, most Hindus (59%) also link Indian identity with being able to speak Hindi. And these two dimensions of national identity – being able to speak Hindi and being a Hindu – are closely connected. Among Hindus who say it is very important to be Hindu to be truly Indian, fully 80% also say it is very important to speak Hindi to be truly Indian.

Interestingly, most Hindus (59%) also link Indian identity with being able to speak Hindi. And these two dimensions of national identity – being able to speak Hindi and being a Hindu – are closely connected. Among Hindus who say it is very important to be Hindu to be truly Indian, fully 80% also say it is very important to speak Hindi to be truly Indian.

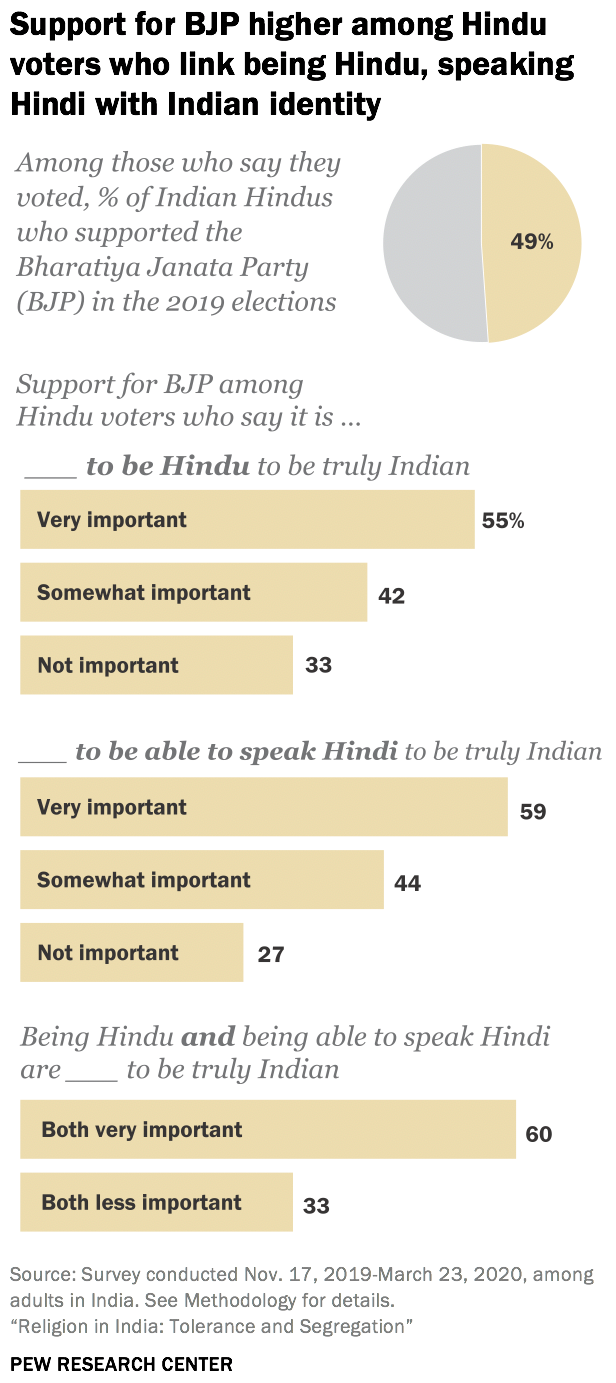

The BJP’s appeal is greater among Hindus who closely associate their religious identity and the Hindi language with being “truly Indian.” In the 2019 national elections, 60% of Hindu voters who think it is very important to be Hindu and to speak Hindi to be truly Indian cast their vote for the BJP, compared with only a third among Hindu voters who feel less strongly about both these aspects of national identity.

Overall, among those who voted in the 2019 elections, three-in-ten Hindus take all three positions: saying it is very important to be Hindu to be truly Indian; saying the same about speaking Hindi; and casting their ballot for the BJP.

These views are considerably more common among Hindus in the largely Hindi-speaking Northern and Central regions of the country, where roughly half of all Hindu voters fall into this category, compared with just 5% in the South.

Additionally, among Hindu BJP voters who link national identity with both religion and language, 83% say it is very important to stop Hindu women from marrying into another religion, compared with 61% among other Hindu voters.

This group also tends to be more religiously observant: 95% say religion is very important in their lives, and roughly three-quarters say they pray daily (73%). By comparison, among other Hindu voters, a smaller majority (80%) say religion is very important in their lives, and about half (53%) pray daily.

Interestingly, even though Hindu BJP voters who link national identity with religion and language are more inclined to support a religiously segregated India, they also are more likely than other Hindu voters to express positive opinions about India’s religious diversity. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of this group – Hindus who say that being a Hindu and being able to speak Hindi are very important to be truly Indian and who voted for the BJP in 2019 – say religious diversity benefits India, compared with about half (47%) of other Hindu voters.

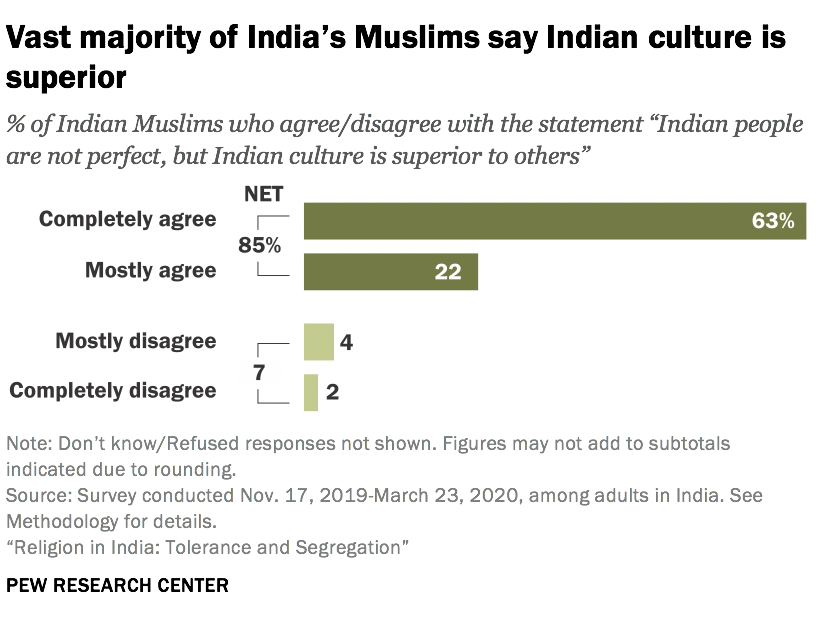

India’s Muslims, the report finds, almost unanimously say they are very proud to be Indian (95%), and they express great enthusiasm for Indian culture: 85% agree with the statement that “Indian people are not perfect, but Indian culture is superior to others.”

Relatively few Muslims say their community faces “a lot” of discrimination in India (24%). In fact, the share of Muslims who see widespread discrimination against their community is similar to the share of Hindus who say Hindus face widespread religious discrimination in India (21%). However, among Muslims in the North, 40% say they personally have faced religious discrimination in the last 12 months – much higher levels than reported in most other regions.

Relatively few Muslims say their community faces “a lot” of discrimination in India (24%). In fact, the share of Muslims who see widespread discrimination against their community is similar to the share of Hindus who say Hindus face widespread religious discrimination in India (21%). However, among Muslims in the North, 40% say they personally have faced religious discrimination in the last 12 months – much higher levels than reported in most other regions.

In addition, most Muslims across the country (65%), along with an identical share of Hindus (65%), see communal violence as a very big national problem.

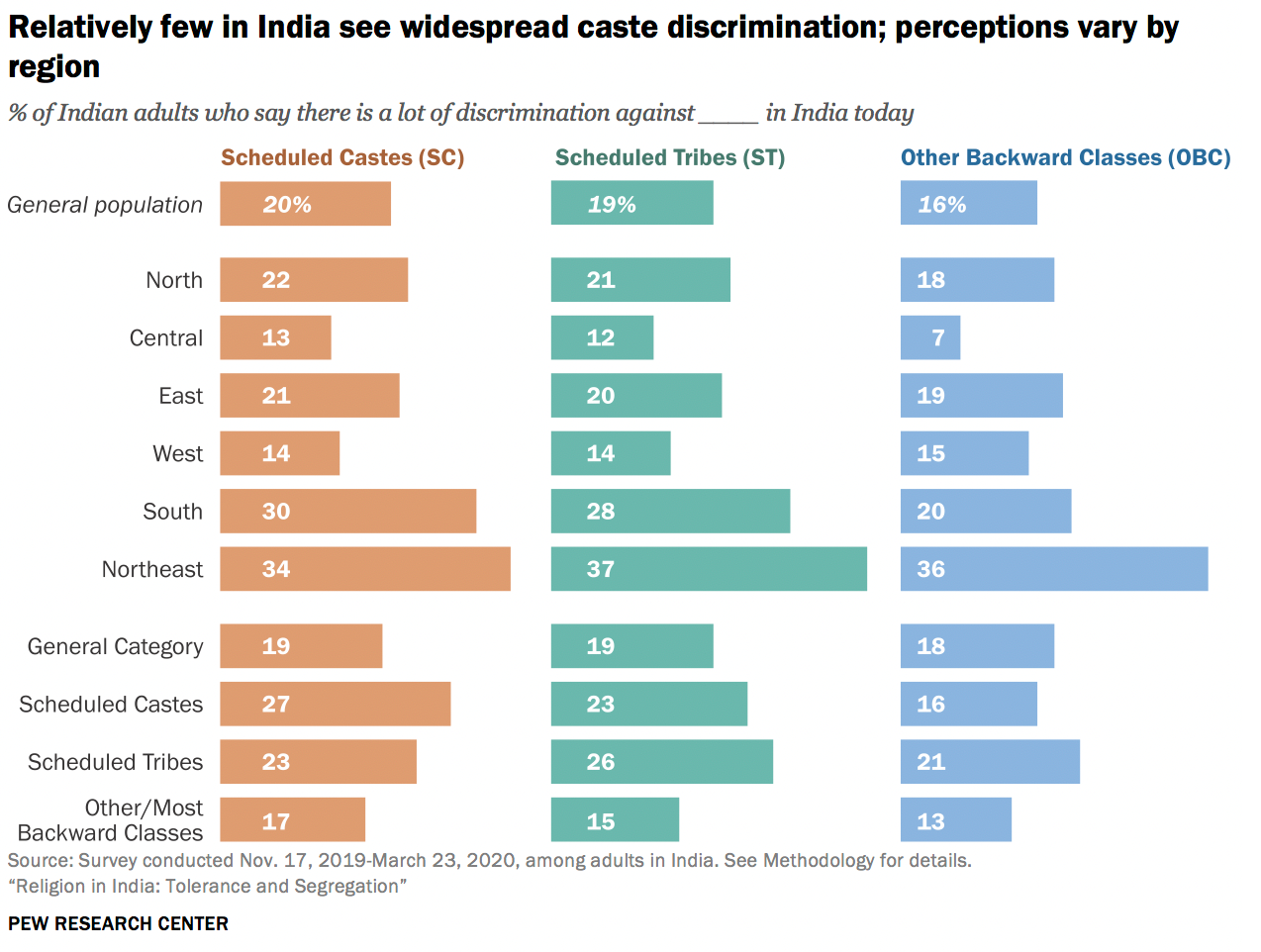

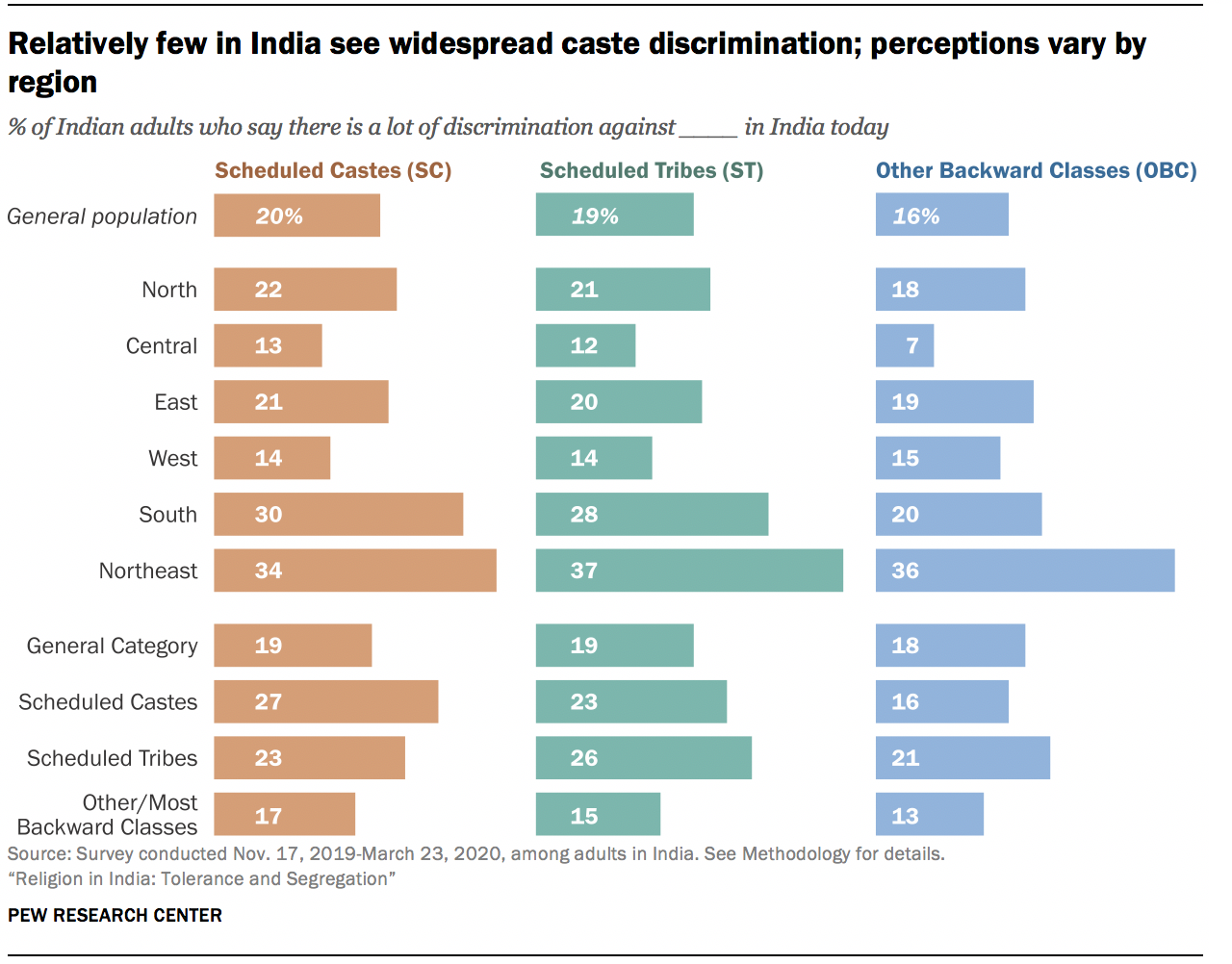

Religion is not the only fault line in Indian society. In some regions of the country, significant shares of people perceive widespread, caste-based discrimination, the report finds.

The survey finds that most Indians do not perceive widespread caste-based discrimination. Just one-in-five Indians say there is a lot of discrimination against members of SCs, while 19% say there is a lot of discrimination against STs and somewhat fewer (16%) see high levels of discrimination against OBCs. Members of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are slightly more likely than others to perceive widespread discrimination against their two groups. Still, large majorities of people in these categories do not think they face a lot of discrimination.

“Although caste discrimination may not be perceived as widespread nationally, caste remains a potent factor in Indian society. Most Indians from other castes say they would be willing to have someone belonging to a Scheduled Caste as a neighbor (72%). But a similarly large majority of Indians overall (70%) say that most or all of their close friends share their caste. And Indians tend to object to marriages across caste lines, much as they object to interreligious marriages,” the report notes.

Overall, 64% of Indians say it is very important to stop women in their community from marrying into other castes, and about the same share (62%) say it is very important to stop men in their community from marrying into other castes. These figures vary only modestly across members of different castes. For example, nearly identical shares of Dalits and members of General Category castes say stopping inter-caste marriages is very important.

You can read the full report here.