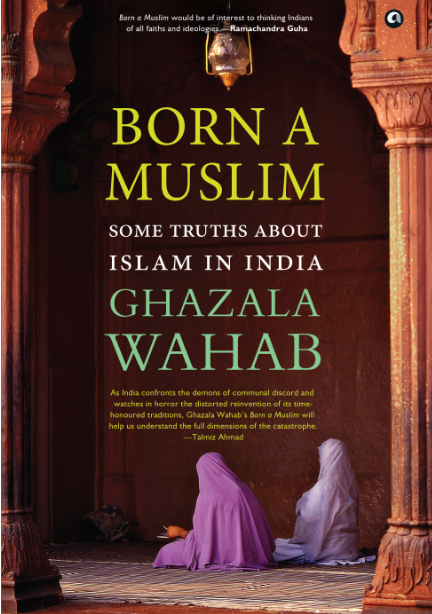

Ghazala Wahab’s Born a Muslim: Some Truths About Islam in India tracks the history of the religion from its revelation in Arabia in the seventh century to its spread through many parts of the world. It arrived in India by multiple routes—in the south, in the eighth and ninth centuries CE, with traders from Arabia, and in the north, in the tenth and eleventh centuries, with invaders, rulers, and mystics, largely from Central Asia. Once it was established in India, it morphed and evolved through the centuries until it took on the distinctive contours of the religion that is practised here at present. The author takes a clear-eyed look at every aspect of Islam in India today.

Weaving together personal memoir, history, reportage, scholarship, and interviews with a wide variety of people, the author highlights how an apathetic and sometimes hostile government attitude and prejudice at all levels of society have contributed to Muslim vulnerability and insecurity.

The following is an excerpt from the book.

Every day we woke up to the news of violence in some part of the city and hoped that all of us would remain safe. Giving us confidence was the knowledge that, in the last decade, my father and uncle who lived with us had cultivated a vast network of friends from among the bureaucrats who had served in Agra; those district magistrates, senior superintendents, and commissioners of police had climbed up the bureaucratic ladder in the Uttar Pradesh state administration. Such was my uncle’s immediate clout that he had managed to get daily curfew passes for himself and my mother. They used the passes to visit riot-affected areas and hand out relief material.

Then the violence hit home. All through that November morning, our neighbours continued to visit us with solemn advice. ‘Shift to your ancestral house for a few days,’ they told my father. ‘Or at least send bhabhiji (referring to my mother) and the kids away.’ Finally, my father booked us a room at the Mughal Sheraton Hotel. My mother drove us to the hotel, leaving my father and uncle at home. However, by late afternoon, anxiety got the better of her. She drove us back home against my father’s orders.

As the day drew to a close, we all huddled together in the family room waiting for the attack that my parents were certain would happen that evening.

As the day drew to a close, we all huddled together in the family room waiting for the attack that my parents were certain would happen that evening. I was handed a diary with the phone numbers of all the police officials we knew, starting from the local police station all the way up to the senior superintendents. I started to make the calls, but none were being answered. ‘Doesn’t matter, keep trying,’ my father said to me.

Then we started to hear the slogans.

At first, they seemed to come from a distance, but slowly they started to come closer. My brother and I ran to the main door, which had a narrow glass panel on the right through which one could see the porch, the gate, and the road beyond. A mob with tridents and flaming torches was marching towards our gate. My brother and I were transfixed at the glass panel-inside, my mother was screaming, asking us to get back. The mob was now at the gate, shouting violently. Right at the front of the crowd was one of our neighbours, a boy whose younger brother was my brother’s playmate.

‘Sanjay bhaiyya,’ my brother whispered and we ran inside to share our discovery.

My father was calm. He told my uncle that Sanjay’s presence implied they would not harm us. “They will shout some slogans and move on,’ he said.

Then we heard the sound of windows smashing as the mob started to throw stones. ‘Get back to the phone,’ my father screamed at me, even as my uncle rushed past him to go to the terrace. He had taken out my father’s licensed revolver. ‘I will fire a couple of shots in the air to scare them,’ he said, taking the steps two at a time.

That evening, no dinner was served. Everyone stayed together in the family room, not daring to step out to assess the damage.

My father panicked. He screamed at my uncle to stop. My mother chased after him to physically hold him back. ‘You fire one shot in the air and they will burn the house down,’ my father yelled at my uncle. It was very likely that he was shaking too.

As long as my father was calm, we feared no disaster. But once he voiced his fears, panic descended on us. Fortunately, my uncle saw sense and calmed down somewhat. In those few moments of pure terror, we hadn’t realized that the mob had started to disperse. Just as the noise outside receded, my call to the SSP’s residence was answered by someone. He made a note of our address and promised to send a patrol car.

Once we were convinced that the silence at the gate was holding, my mother went to the door to confirm that the mob had really left. One of the glass panels had cracked and from the shattered pieces of glass on the porch we figured that several windows had succumbed to the assault as had the car parked in the porch. That evening, no dinner was served. Everyone stayed together in the family room, not daring to step out to assess the damage. Well after ten at night, a few policemen arrived. My father and uncle went out to speak with them; everyone else was instructed to stay inside. The police assured us that they would include our lane in their night patrol and that we should rest in peace.

Somehow, we got through that night. I believed that everything would be fine in the morning. And it was, for a few hours, when our domestic help started to arrive for work. Since ours was not a Muslim area there was no curfew here. Just as we were settling down for breakfast, someone rang the doorbell.

It was my cousin, my middle uncle’s older son from the mohalla. Five years younger than me, and still in school, he was dishevelled and quaking with fear. He must have been crying for some time because his voice was hoarse. That morning, the notorious Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC)1 had carried out a cordon and search operation in our old mohalla and had taken away the adult men. My cousin had also been picked up along with his father and younger uncle. However, one of the constables took pity on him and allowed him to jump out of the jeep as it turned onto the main road. From there, he walked the couple of kilometres to our house. During the operation, the police ransacked the house, disconnected the telephone lines, and broke the television sets. My two aunts and younger cousins were at the house but we couldn’t reach them because of the curfew orders in that area. And there was no way of knowing where my uncles were. Though I didn’t realize it at that time, memories of the Hashimpura massacre2 must have sent cold shivers down the backs of my parents and uncles.

During the operation, the police ransacked the house, disconnected the telephone lines, and broke the television sets.

Leaving the breakfast untouched, my father and my uncle left immediately. My uncle went to the police station next to the mohalla. He was told by the constables there that no such arrest had taken place. But when my uncle insisted he had received the information from reliable sources, he was asked to go to another police station. Convinced that the constables were lying, he stayed put. No officer came to speak with him. My father went to see the police commissioner who had been a guest at our home on several evenings, sharing drinks with my father. At the police station, my father was told that the commissioner was not available, after which he tried the office of the SSP, another regular at the parties at our home. The SSP briefly met my father, seeming extremely busy, and told him that he was not aware of any such incident.

But he assured my father that if they had been arrested, he would ensure that my uncles would not be harmed. Word was passed down the hierarchy. My uncle was handed a few additional curfew passes. He was also told not to worry and that my missing uncles would return home before the evening. With no other choice, he came back. By that time my father was home too.

They told us how my uncles were dragged out in their sleepwear, how a few policemen came back inside to deliberately break things, how they made salacious remarks about my younger aunt, how they scared the kids.

I accompanied my mother and uncle to the house of my birth in my uncle’s hatchback which, having been parked inside the garage, had escaped the vandalism of the previous evening. The open maidan at the mouth of lane in which our house was located looked like a war zone. Stones were scattered all over the unpaved ground, and there were a few carcasses of two-wheelers. The windows of the houses facing the maidan were broken and most of the doors hung by their hinges. Leaving the car next to the police tents, we walked with great trepidation along the lane towards our house. From the outside, it looked normal. My grandfather had installed a heavy-duty door which had withstood the assault. As always, it was not bolted.

A gentle push opened it. In the central courtyard, the first thing that caught my eye was a Sony television lying face down on the marble floor. Then the pieces of glass, remains of crockery came into the view, and clothes, and toys, and a cricket bat, and the heirloom copper paandaan (an elaborate case in which betel leaves and their accompaniments are kept), and other debris that I could not identify. However, more frightening than this havoc was the eerie silence that permeated the house. When I was growing up there, I always associated this house with noise. There were far too many people in too small a space. But now that there was no sound, my stomach tightened and my legs felt heavy. Where was everyone?

My mother called out to my aunt with what sounded like a shriek. My aunt screamed in response and came tearing out from the room next to the mazar where we used to light incense every Thursday. All at once, the noise returned. My aunts, distraught and dishevelled, rushed out and engulfed my mother in a frightened collective embrace. I tried to hug my cousins but we were all a little embarrassed. We never embraced, even though we used to play together, gossip, and tease one another. So we hung around, looking uncomfortably at the mess strewn around us even as my uncle darted in and out of rooms, taking stock of the damage.

Now my aunts started to recount what had happened, frequently interrupting themselves with loud wails. They told us how my uncles were dragged out in their sleepwear, how a few policemen came back inside to deliberately break things, how they made salacious remarks about my younger aunt, how they scared the kids, and so on. It took me a while to realize that both my mother and I were crying. Perhaps we were crying for my uncles or at the narrow escape that my aunts had had or because of what could have happened to us the previous evening.

When it came to communal division, they were nothing but Muslims, Forever suspects, forever scapegoats.

But I knew for sure that some of my tears were for the sheer helplessness that I knew my father and my uncle were feeling. Physically they may have travelled a small distance from the Muslim mohalla to an upper-class Hindu colony but emotionally they had travelled the distance of a lifetime. In the family comprising six brothers and four sisters, these two men had most visibly shed their ghettoized Muslim identities. They were at home in the social, cultural, and economic life of Agra, hobnobbing with the who’s who of the city. And yet, when it came to communal division, they were nothing but Muslims, Forever suspects, forever scapegoats.

1. Prabhu Chawla, ‘Provincial Armed Constabulary of Uttar Pradesh becomes focus of controversy’, India Today, 15 Oct 1980.

2. During the 1987 communal violence in Meerut, men from the Provincial Armed Constabulary rounded up about forty-five Muslim men in a late-night raid. Instead of taking them to the police station, the PAC took these men to the Upper Ganga Canal in Murad Nagar in Ghaziabad district, where they started to kill them one by one. The bodies were thrown into the canal. Since this was next to the highway, the massacre was interrupted by passing vehicles. After some time, the surviving men were driven to the Hindon River Canal in Ghaziabad where they were eventually killed. Activists filed a case against the PAC; this case dragged on for several years and, in 2015, a district court acquitted all the PAC accused for want of evidence. An Indian Police Service officer, Vibhuti Narain Rai, who was the superintendent of police in Ghaziabad district at that time, was the first person to reach the massacre site and file a first information report (FIR). He later recounted the horror of the incident in his book Hashimpura 22 May: The Forgotten Story of India’s Biggest Custodial Killing, Gurgaon: Penguin Books, 2016.