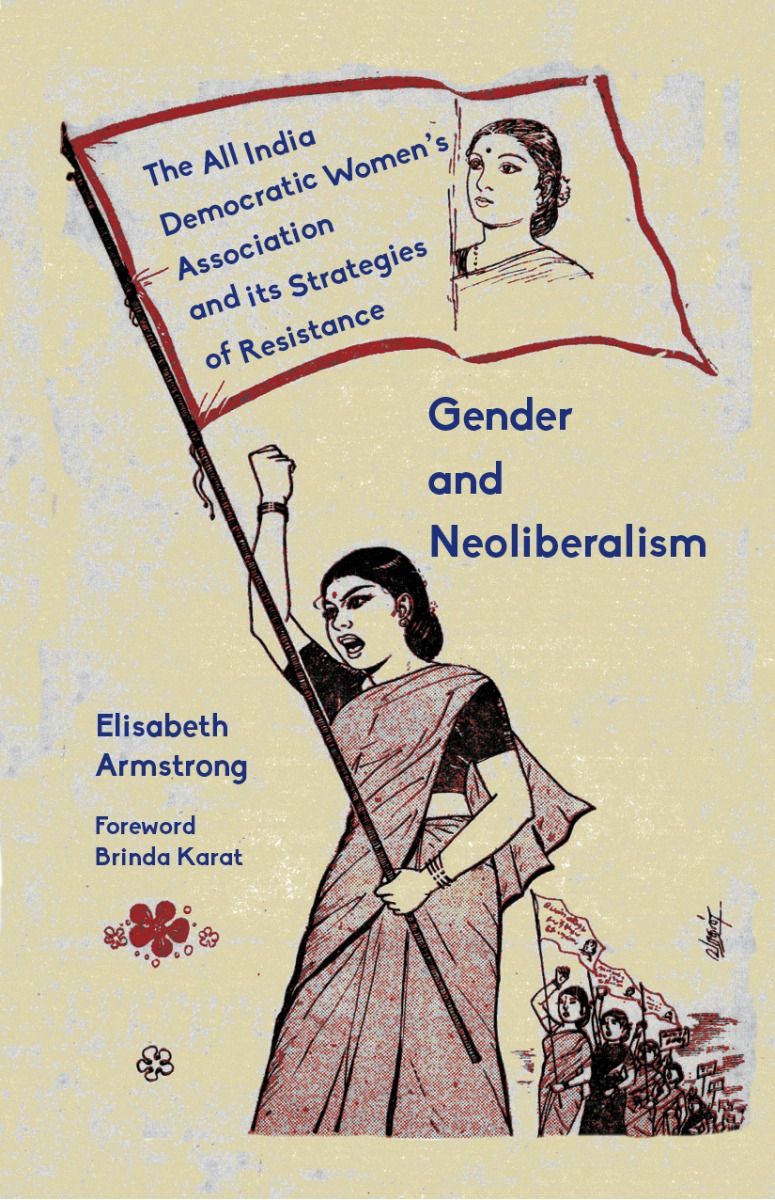

Elisabeth Armstrong’s Gender and Neoliberalism: The All India Democratic Women’s Association and its Strategies of Resistance describes the changing landscape of women’s politics for equality and liberation during the rise of neoliberalism in India.

The following are excerpts from the Introduction and chapter “Origins” of the book.

From Introduction

A central question of this book is how AIDWA managed to grow so rapidly across India, with its strength built from among the women most severely disenfranchised by neoliberal policies and governance. My contention is that during the 1990s, AIDWA pivoted away from its earlier understanding of primarily organizing women around common issues that crossed class and community locations, toward a new theory of inter-sectoralism that enabled its success. As it grew to become a large mass organization for women, activists at local levels developed methods that successfully organized people within and outside of their workplaces, inside their communities, and beyond the norms of those community affiliations. In the process, intersectoral organizing created a stronger organizational fabric to resist the fragmentation of and competition between peoples and interests that are the hallmark of neoliberalism.

During the late 1980s, state and national leaders of AIDWA began to develop a sectoral theory of women’s gendered lives. A sectoral theory of women’s lives embeds an understanding of those social groupings in a systemic and historical class analysis. The term sectoral is not a new one: sectors or sections are words used interchangeably by members to describe the particular social groupings (such as those around religion, caste, class, location, and work status) that structure a polity and define people’s lives within that polity. Early on in their organizing, AIDWA members defined sectoral issues nominally more than analytically. That is, sectoral issues denoted the specific needs of a sub-category of particularly oppressed women that demanded greater knowledge and targeted political attention. After the anti-Sikh riots in Delhi in 1984, the visibility and political mobilization of anti-Muslim and other communal tensions rose. In the early 1990s, liberalization policies infiltrated into Indian governance itself.

At the core of this book are the stories of many women who worked at all levels of the organization, from local unit members to national leaders, who lived mainly in rural Haryana or in rural and urban parts of Tamil Nadu and New Delhi.

[…]

From Origins

Pappa Umanath was one of AIDWA’s founders who came out of the explosive organizing of twentieth-century India. Hailing from the southern state of Tamil Nadu, Pappa’s vision of AIDWA had a regional specificity, but also a national dimension as an office holder in the organization for many years. Her metaphor for the interlocking qualities of struggles and movements across time and location that developed into AIDWA was the banyan tree. ‘Like the roots of the banyan tree that spread out as the tree grows, forming many trees that are linked. We formed a national women’s organization to fight for the majority of women who face oppression and injustice.’

This chapter tells the history of AIDWA’s formation through one primary regional lens, that of one founding member’s life in the southern state of Tamil Nadu. Attention to the regional specificity of AIDWA’s history reflects national and international movements, ideologies, and solidarities as they impact local organizing.

Pappa’s story does not tell of middle-class women’s involvement in social reform and nationalist movements. Instead, her autobiography emphasizes women activists who were working-class, working-poor, and agricultural workers.

Pappa Umanath’s own political initiation traversed the cusp of Indian independence—from 1943 when she first joined the Balar Sangam and courted arrest, to 1948 when she joined the Ponmalai Women’s Association.

Pappa’s story of AIDWA’s origins weaves together the intersecting movements that shaped her earliest experiences. Her story reveals how these movements nurtured AIDWA’s formal inception in 1981 and its growth in subsequent years. Born in 1931, named Dhanalakshmi, Pappa got her nickname where she spent the formative years of her childhood in Ponmalai, a town near Tiruchirappalli in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, in a railway housing colony called the Golden Rock Railway Workshop. Early in Pappa’s childhood her father died, leaving her family destitute. She moved to Ponmalai with her mother, named Alamelu (but called Lakshmi), and two older siblings, to live with her uncle in the railway colony. As a widow, her mother depended upon her kinship ties and her ability to work in order to support her family. Even her ability to work was not always enough since employment options for widows, regardless of their caste, class or social status, were very limited.

Pappa’s mother, Lakshmi, survived as part of the informal economy dependent on the railway industry, by selling idli snacks to railway workers with the help of her children. Lakshmi shaped her anti-imperialist political commitments to her work’s mobility and participated in the freedom movement as a messenger. Pappa described her mother’s influence on her own activism with due pride:

Some [women] were involved in guerrilla struggles, satyagraha [Gandhian national independence campaign], going to jail. After independence we fought so that white men’s actions would not be repeated. We had to fight against the incoming Congress party. My mother was not literate, but she taught me to be sensitive to the political issues of the day. During the underground days of the Party [Communist Party of India or CPI], she safeguarded Party letters. She hid the letters in her hair and carried a basket on her head. She could never read the contents of the letters because she was illiterate. Her job was to deliver the letters, to meet Party members secretly, and to deliver food to them so the British authorities would not detect them. I am proud of my mother’s work against the British and my own work against imperial rule. (Pappa Umanath interview, 26 March 2006)

In 1948, when Pappa was 15, her mother Lakshmi helped to organize women in the railway colony into the Ponmalai Women’s Association (PWA), another primarily neighbourhood organization linked to the CPI. The Association functioned in part as a women’s committee of the workers’ union, to support union strikes, and to fight against police and company sanctions that targeted politically active workers (P. Menon 2004, p. 110). The PWA also included many women who did not have direct ties to the union, but who lived in the neighbourhoods of the Golden Rock railway colony. Pappa joined this group immediately.

[PWA] sought to build leadership among all women, rather than concentrating primarily on wage-based women workers.

Pappa described her own childhood reactions to patriarchal control in this context:

I was a small girl at the time. Everyone in our colony was a member [of the Ponmalai Women’s Association]. She [her mother, Lakshmi] began to challenge matrimonial issues and atrocities against women. I hate male chauvinism. Even as a small girl I would ask why women are held in low esteem. Only with that anger can we build a women’s organization. Why shouldn’t women raise their voices against beating wives? All women are against this. My mother fought against this violence in her time. (Pappa Umanath interview, 26 March 2006)

In 1943, the same year Pappa joined the Balar Sangam, she also courted arrest by joining a Non-Cooperation movement procession against the British occupation of India.1 She described her own individual and collective aspirations many years later: ‘The judge asked me why I joined the Non-Cooperation movement. I said, “To wipe you all out.” The judge asked, “Can you?” I replied, “Yes, I can. That is why I am here” ’ (Pappa Umanath interview, 26 March 2006). Pappa told of her disappointment when the judge refused to jail her for her activities due to her young age. ‘I cried as I lay on my mother’s lap. My mother comforted me saying, “That’s okay if you could not go this time, you can go another time.” She gave me courage. My mother was illiterate, and her words surprised me’ (ibid.).

Lakshmi, Pappa’s mother, strengthened her daughter’s courage to fight colonial power, even as she modelled that resolve in her own activities. Still, Lakshmi’s encouraging words to the 12-year-old Pappa surprised her. Pappa’s expressed surprise may refer to her mother’s economic vulnerability and illiteracy, or to the extent of her political militancy even as it extended to her young daughter, or perhaps a combination of both these aspects. Lakshmi grounded her commitment to class, gender, and national struggles by the dangerous act of passing notes to underground revolutionaries, not through writing or even reading those notes. Lakshmi’s support for Pappa’s aspirations to do jail time might upend our own expectations: that the nationalist movement largely was an elite affair, for the literate and well-connected subjects of British India. Many, though certainly not all, histories of anticolonial movements have taught us that the movement was led by men and their wives, daughters and sons, and not made up of poor working women and girls. In the tradition of subaltern history writing, Pappa’s expressed surprise clears rhetorical space to register how her story overturns dominant assumptions about the Indian freedom movement.

Perhaps Pappa’s story of passing her knowledge to her daughters lies within her own story of AIDWA’s origins—origins that began with her own political formation as a girl surviving on the margins of the militant working-class railway unions of pre-Independence India. She answered my repeated requests for AIDWA’s beginnings not with the dates of its founding conference, but through mining her own and her mother’s anti-imperialist, communist, and feminist past. She also answered by remembering the social reform movements of the nineteenth century for their Indian instigators and for their ongoing importance within the fabric of radical communities, not for the British public’s horror at child marriage and widow immolation. Pappa’s story, like AIDWA’s, is not just a story of resisting British colonialism, but of fighting imperialism as it continued to structure the new nation of India in favour of the wealthy, and against the redistribution of power, land, and resources to the organized and unorganized working people.