To find her place in the world, Prema must not only leave her abusive husband and bring up her daughter on her own, she must also fight oppression at the workplace and form strong friendships with other women. She gives voice not just to her own story but also, by extension, to the stories of thousands of women of her generation, women who grew up in the heady years immediately following the formation of an independent Indian nation state.

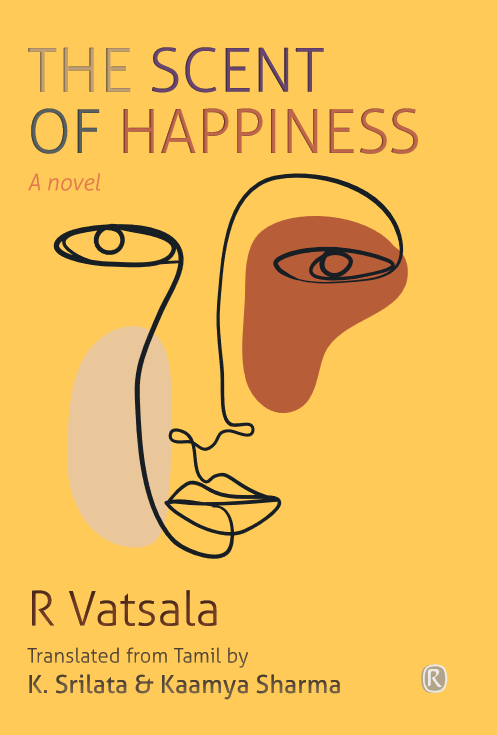

Translated into English by K Srilata and Kaamya Sharma, R Vatsala’s The Scent of Happiness (Ratna Books) is a sharp critique of gender politics as it plays out both in the private, familial sphere as well as in the public sphere.

Amma often stitched blouses for herself. She also designed and tailored a variety of frocks for Prema, embroidering flowers on them. As soon as she was done making a new frock, she would give Prema a bath and try the frock on her. Early morning or late in the evening – she did the same.

As she went about her stitching, Amma told Prema stories about herself. She told her about how she had been raised like a queen, about her rich father and the many bungalows he owned, about his habit of taking loans and frittering away all his wealth, about his turning a pauper, about how he had been left with no option but to get Amma married to a mere clerk before his death, about how paatti and all her uncles were left destitute, about how she had consoled them and taken them under her wing, about how “ungrateful” they had all turned out. Sometimes it was these sorts of stories that she told. At other times, her stories revolved around her father’s brothers’ wives. Amma also spoke to Prema about the hard time Ambujam Atthai gave her. Prema only understood these stories partially. And yet, they remained forever etched in her memory for she had heard them so many times. When her dresses came out right, Amma would be all excited. Prema would then ask her to narrate the story of the time she was born.

Amma would begin, “The day before your birth I was very happy. This was because we had managed to fix sunshades on the windows and the gate of paatti’s house. Everything had gone the way I had planned it. And this was only because I had paid the labourers. Do you know how I managed that? I used the money I had put aside from what Appa sent me every month. Do you know how I put aside that money? I never bought any vegetables. I instructed paatti to make do with the spinach that grew in the garden. In this way, I saved the money that I would have otherwise spent on vegetables. Since you were in my stomach, the doctor advised me to drink milk and to eat fruit. But I ignored his advice. That is how I was able to save all that money. The money came in handy when the labourers’ wages had to be paid.

Once, all the work was done, I washed the entire house myself with buckets and buckets of water. Paatti bought some mangoes from the fruit seller that day. That night, I went to bed after eating some curd rice and two slices of mango. The moment I laid my head on the pillow, I felt a sharp pain in my belly.

“When the pains start, send word to Ambujam Atthai on the next street. She and her husband will take you to the nursing home,” Appa had instructed us. So Rajamani maama went to them at once with the news. Atthai and her husband took me to Shantakumari’s nursing home in a hand-drawn rickshaw. “The delivery will not happen now,” the doctor said when she saw me, “There’s still a lot of time.” You see, she lived just up the stairs from her clinic. After declaring this, she went right back to sleep. Atthai and her husband returned to their house.

When she reached this point in her narrative, Amma invariably paused for effect and Prema always chimed in, “But at around four in the morning, my head peeped out of your stomach. Alarmed at the sight, the nurse rushed to fetch the doctor. I was born at once!” Amma would join her, “Yes, you were!” This delighted Prema no end.

***

As soon as they returned to Delhi, he took her to see the Qutub Minar, the Taj Mahal and the Delhi fort. Prema couldn’t shake off the feeling that for some reason he was afraid of Amma and that he was taking her sight-seeing only because Amma had asked him to.

He would walk really fast. Heavy with child, Prema would not be able to keep up. He would walk on ahead and wait for her, irritation writ large on his face. The moment she caught up with him, he would be off again, at top speed. It was in this manner that they had seen all the sights – Qutub Minar (she had not been able to climb it, he had climbed all the way to the very top), Taj Mahal, Delhi fort…

As she gazed at the Taj Mahal, her thoughts travelled to Mumtaz Begum and Shah Jahan. When Mumtaz Begum was alive would Shahjahan too have walked a mile ahead of her the way her own husband did? Mumtaz had died during childbirth. She had been an old woman then. Had the fetuses in her womb been the result of lust, or had love been responsible for their creation?

Also read | R Vatsala on The Scent of Happiness

Was it true what they said – that Shahjahan had chopped off the fingers of the labourers who had built the Taj Mahal so they would never again build anything else like that? If that was indeed so, what did it even mean – this marble structure that had resulted from forced labour, that had sucked dry the blood of so many? What did it symbolize in the end – the wonderful love that a man was capable of or, merely, a king’s arrogance, his desire for fame? She felt she had seen enough and sat down completely exhausted.

The guide called to them, “Come. I will show you the spot from which Shahjahan viewed – in a small mirror – the reflection of the Taj Mahal after he was imprisoned by Aurangazeb.” Prakash bhaiya had told Prema about this. She had felt sorry for Shahjahan then. But now her faith in the love of real human beings had diminished greatly. She did not go where the guide called them. Her husband went by himself (perhaps he did not want to waste the money he had paid the guide).

Prema had once watched the actress Madhubala dancing to the song Pyar Kiya to Darna Kya in the film Mughal-e-Azam. She had enjoyed seeing the shimmer of a thousand images of Madhubala reflected in the round mirrors embedded in the ceiling of the courtroom sets. Apparently, the sets had been prepared along the lines of a room in an actual palace in Agra, a room whose ceiling was decorated with mirrors. Prema longed to visit the original palace in Agra so that she could better imagine the scene she had once watched. However, her husband refused to take her there because it would cost too much money. “Who knew whether the real Salim and Anarkali loved each other as much as Dilip Kumar (who had played Salim in the film) and Madhubala (who had played Anarkali) loved each other both on and off screen? May be it was all just a made-up story – that Salim and Anarkali loved each other? What was the point, after all, in visiting that glass palace?” Prema consoled herself with these thoughts.

When they emerged, they found a small girl hawking bead necklaces for eight annas a piece. Prema’s heart went out to her. She decided to buy a necklace from her. But her husband refused to let her. He claimed he didn’t have the money for it. Prema pleaded with him until he relented and got her the necklace. They returned at ten that night, and went to bed after eating some leftovers. Thus ended the story of their visit to that world famous monument to love.