To find her place in the world, Prema must not only leave her abusive husband and bring up her daughter on her own, she must also fight oppression at the workplace and form strong friendships with other women. She gives voice not just to her own story but also, by extension, to the stories of thousands of women of her generation, women who grew up in the heady years immediately following the formation of an independent Indian nation state.

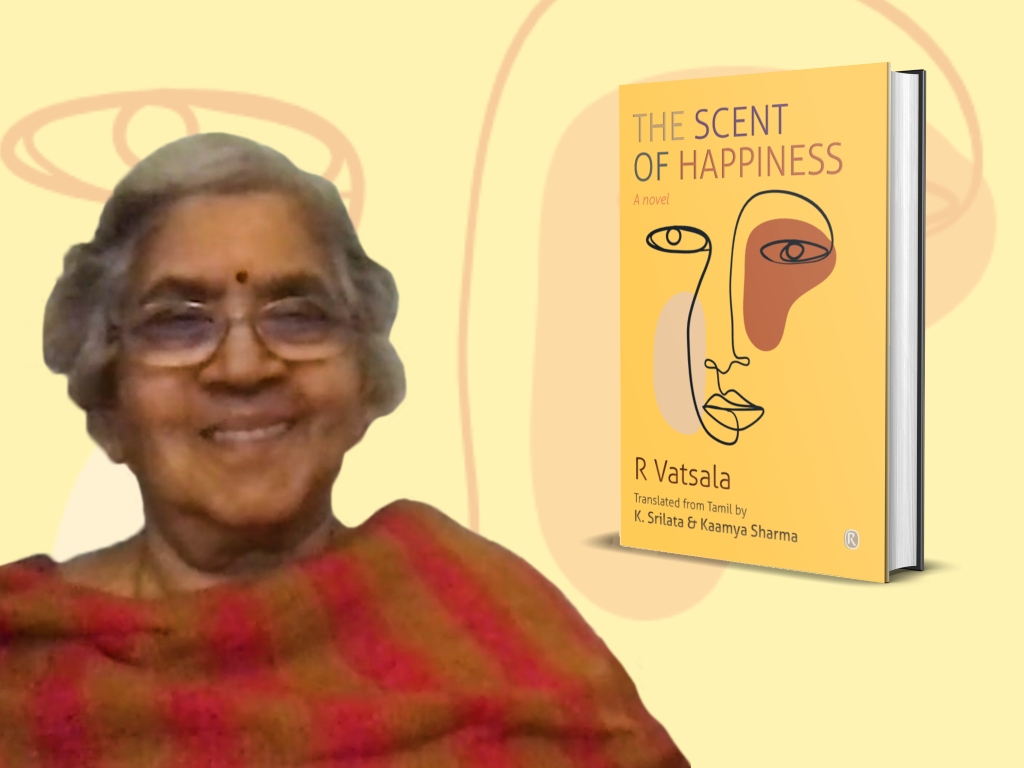

Translated into English by K Srilata and Kaamya Sharma, R Vatsala’s The Scent of Happiness (Ratna Books) is a sharp critique of gender politics as it plays out both in the private, familial sphere as well as in the public sphere.

In this conversation with the Indian Cultural Forum, Vatsala talks about her book and more.

ICF: The protagonist Prema, despite her abilities, suffers from the internalisation of her inferiority. Her journey takes her from this point to a sense of self-worth. Would you compare her situation with the generation before her – her mother – and the one after – her daughter? In other words, what has changed, and what has remained the same?

Vatsala: Much has changed for sure, and for the better. There has been considerable progress over successive generations of women. In my novel, the character Prema’s mother Janaki, is an intelligent and confident girl before her marriage. This is because her father thinks the world of her intelligence and beauty. He plans to educate her up to school final, something that is unheard of for girls of her generation. He also hopes to get her married to a man of “high status”. But due to a decline in his income, he is forced to get her married to a widower, a clerk who is several years older to her. During the first few years of her marriage, Janaki has to adjust to life within the confines of a conservative Tamil Vaishnavite joint family. Her husband is far too conservative to openly acknowledge his admiration of her beauty and talents. Her in- laws only criticise her for not knowing being well-versed in the Vaishnavite tradition. Janaki’s self worth takes a beating. Despite her intelligence, she internalises society’s views on women and ends up believing that it is she who lacks something because her husband is not sexually attracted to her. On the other hand, Prema refuses to allow her husband to have sex with her when she realises that he does not love her. She has self-worth enough for that. And Prema is able to take the decision to live without a husband. While both these decisions of Prema’s are atypical for her generation, they were at least possible. They would have been unthinkable though for women of Janaki’s generation. But in spite of having the courage to take such decisions, for many many years, when it comes to judging the level of her own intelligence, Prema only mirrors the opinion of males who she thinks know everything. These men include her brother and the professor Sriraman. This is how she has been brain washed by society. This changes only when she is exposed to feminist thinking and feminist politics.

The novel does not talk about the mindset of Prema’s daughter Deepa. But given the fact that she was brought up by a woman like Prema who had not been cowed down by her husband, given that Deepa was educated in an institution known for nurturing ideas, given that she had chosen her own life partner, leads the reader to assume that she has high levels of self-worth.

ICF: The novel piles small details of everyday life meticulously. Sometimes, these details are almost mind-numbing. Was this consciously done to bring into public space the almost invisible drudgery of a woman’s daily life?

Vatsala: None of this was planned beforehand! That is the way I see things, the way I think. Whenever I think about people or a situation, I visualise the entire scene of which they are a part. The tiny details come along with all this. It is an automatic process! For instance, from the balcony of my apartment, I can see a street full of people rushing to and fro from work morning and evening. I imagine their lives at home, especially the lives of women. This visualisation or attention to detail is, as far as I am concerned, an integral part of storytelling.

ICF: There is a quiet undercurrent of the protagonist Prema questioning what a more fulfilling relationship between a man and a woman might be like. But the resolution of the novel takes place when Prema finds friendship and solidarity with other women. Would you comment?

Vatsala: First of all, the way Prema is raised and later trained by her mother makes her shy away from male friends. Following her divorce and her decision never to remarry, Prema gets her satisfaction from doing a good job as a mother as well as from building a career. The labour that this entails along with the constant attention her mother demands from her leaves her with very little time for any kind of friendship. The society that surrounds her will not take kindly to a divorced woman befriending a man or getting close to him. Moreover, her friendship with Neela and the women’s conference she attends which makes a huge impact on her makes her realise that friendships with women are invigorating. In writing about this, I have drawn quite considerably from my own experiences.