Radical Constitutionalism: Towards an Ambedkarite Jurisprudence

The right which is grounded by law but is opposed by society is of no use at all.

—Ambedkar (quoted in Jadhav 2013: I, 186)

This tyranny of the majority must be put down with a firm hand if we are to guarantee to the untouchable the freedom of speech and action necessary for their uplift.

—Ambedkar (quoted in Jadhav 2013: I, 232)

[The Constitution only] contains legal provisions, only a skeleton. The flesh of the skeleton is to be found in what we call constitutional morality. [The framework of constitutional morality would mean that] there must be no tyranny of the majority over the minority … The minority must always feel safe that although the majority is carrying on the Government, the minority is not being hurt, or the minority is not being hit below the belt .

—Ambedkar (quoted in Jadhav 2013: I, 292)

Without equality, liberty would produce the supremacy of the few over the many. Equality without liberty would kill individual initiative. Without fraternity, liberty and equality could not become a natural course of things. It would require a constable to enforce them.

—Ambedkar (Lok Sabha Secretariat 1949, 979)

Ambedkar’s presence in the politics, culture, and society of contemporary India is ubiquitous. (1) Innumerable statues of Ambedkar holding the Constitution in his hand and looking into the distance dot villages, towns, and cities around the country. For the Dalit community, these statues symbolize pride in the achievements of Ambedkar as well as a continuing resistance to caste-based oppression. Though the Constitution was central to the Ambedkar which India has chosen to remember (Baxi 1995, 122–49), (2) there has been only scattered research into understanding what Ambedkar’s contribution was to thinking about the law, apart from the epithet that Ambedkar was the ‘father of the Indian Constitution’.

At least until recently, Ambedkar was ‘ritually celebrated’ even as he was ‘intellectually marginalized’. Professor Baxi tellingly notes that ‘the Indian social science landscape has disarticulated Babasaheb Ambedkar by studious theoretical silence’ (1995, 122–49). (3)

In this climate of silence, Professor Baxi asserts that Babasaheb Ambedkar was the originator of the idea of the ‘lawless laws of Hinduism’, which not only denied ‘equality before the law as a principle to the untouchables, thus erecting a permanent edifice of subalternity over them down the ages’ but also ‘inscribed the extra territorialisation of whole communities of human beings and their castigation as being outside the pale of humanity’ (1995, 141).

However, while the ‘lawless laws of Hinduism’ were what enabled the expulsion of Dalits from the political community, it was law to which Ambedkar turned in order to right the millennial wrongs of history.

Ambedkar’s vision of the law was deeply rooted in his own experience of discrimination under the rigid laws of caste. It was arguably this experience of suffering due to the caste laws authored by society which turned him to the unceasing quest to combat caste discrimination through various forms of law and love. He experimented with norm creation through the prohibition of untouchability and ceaselessly sought to operationalize the norm through a close attention to procedure. He introduced the term ‘constitutional morality’ to public and constitutional discourse to make the point that Indian democracy must not be founded on majoritarianism but rather on a constitutional ethic of respect for dispersed and powerless minorities. While working closely with law he was intensely aware of its limitations, as seen by his advocacy of the concept of fraternity. Fraternity, in his understanding, pushed positive law to its limits, as its operationalization had to be premised on a form of love of a citizen for her fellow citizens.

Caste as Law

When Balagopal asserts that in India ‘caste was the law for centuries’, what does it mean? Is caste law a command of the sovereign in the Austinian sense or do we rather understand caste law, following Hart, as a system of rules that impose obligations which members of a society accept and are in the habit of obeying (Hart 2012)?

Clearly, if we have to think of caste as law, we have to go beyond the idea that it is a command of the sovereign and should be able to account for the fact that the rules of caste have a deep-rooted acceptance within the Hindu society, corresponding to what Hart would call ‘an internal point of view’. (4) Caste-based norms govern every aspect of human behaviour in the society, and a large majority of persons accept and are in the habit of obeying norms which they see as just. In some cases where these norms are violated, members of the society take vigilante action to punish the violators. Other cases of violation of these norms are adjudicated upon by caste-based Panchayats, which then prescribe punishment.

Also Read | The power of counter-ritual

It is Ambedkar’s deep insight that unless one came to terms with the system of caste law it would not be possible to even speak of the rights of the Dalit community. Ambedkar comes to the question of rights and law from his personal experience of being at the receiving end of caste-based discrimination. The young Ambedkar notes:

I knew that in the school I could not sit in the midst of my class students according to my rank but that I was to sit in a corner by myself. I knew that in the school I was to have a separate piece of gunny cloth for me to squat on in the class room and the servant employed to clean the school would not touch the gunny cloth used by me. I was required to carry the gunny cloth home in the evening and bring it back the next day. (Ambedkar 1990)

This lifelong experience of discrimination in all aspects of social life arguably became the basis of Dr Ambedkar’s viewpoint that to understand law in India one had to go beyond State law.

Custom is no small thing as compared to law. It is true that law is enforced by the state through its police power and custom unless it is valid is not. But in practice this difference is of no consequence. Custom is enforced by people far more effectively than law is by the state. This is because the compelling force of an organized people is far greater than the compelling force of the state. (Moon 2014: V, 283)

The fact that the rules of caste enjoy the status of law in Indian society has the inverse implication that laws prohibiting caste-based behaviour suffer from a lack of social legitimacy. In this context, Dr Ambedkar doubts whether the rights which guarantee the Untouchables freedom from discrimination have the character of

rights at all.

As he puts it:

Law guarantees the untouchables the right to fetch water in metal pots. … Hindu society does not allow them to exercise these rights. … In short, that which is permitted by society to be exercised can alone be called a right. The right which is grounded by law but is opposed by society is of no use at all. (Jadhav 2013: I, 186)

From Ambedkar’s writings one can identify three factors which make caste law such a powerful system of subjugation. At the first level, in Ambedkar’s understanding, caste law has behind it the authority of society, and these norms, in turn, derive from religion. He says, ‘[S]ocial force has an imperative authority before which the individual is often powerless. In the matter of a religious belief the imperative authority of the social force is tempered as steel is by the feeling that it is a breach of a graver kind and gives religious sanction a far greater force than a purely social sanction’ (Moon 2014: V, 180).

At the second level, it is the divine authority of caste law (which Ambedkar traces to the Manusmriti) which emboldens the ordinary Hindu to feel that vigilante action (even if unlawful) to punish the supposed infractions of caste law is justified. Ambedkar painstakingly documents myriad incidents of brutal violence against the Dalits who violated the caste law and the impunity of those who perpetrated such violence, and traces such impunity to the sanction of religious codes. These systematic acts of violence spread the fear that any infraction of the caste law would result in severe consequences (Moon 2014: V, 35–61).

At the third level, violations of caste law are adjudicated upon by a caste Panchayat which arrogates to itself the authority to punish the supposed infractions. Ambedkar cites instances when the ‘chavadi’ (public assembly) courts have inflicted their ‘lynch law’ against Dalits. The lynch law consists of arbitrary punishment meant to strip the Dalit of both humanity and dignity. The apposite analogy to the arbitrary punishments meted out by the chavadi courts is the punishments meted out by the British post the Jallianwala Bagh massacre when Indians were made to crawl on the road, flogged on the street, made to salaam all British persons, and so forth. Both aimed to rob the human being of what Ambedkar was to call the ‘title deeds of his humanity’. The only difference being that in one case the British authorities were inflicting the punishment, while in the other it was the Indians themselves (Moon 2014: V, 120).

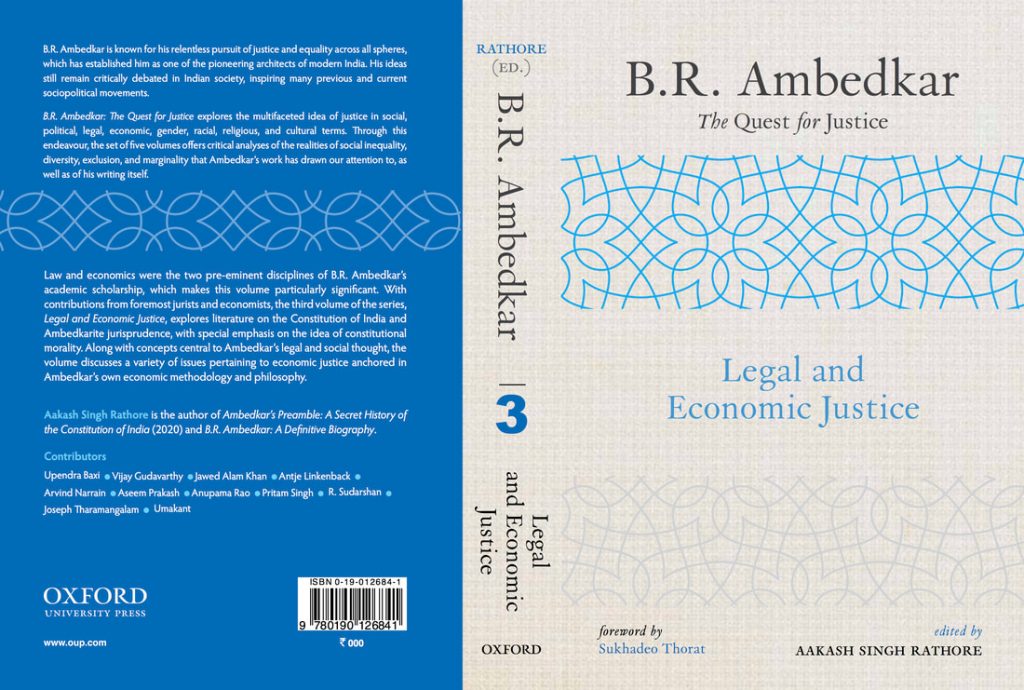

Also Read | On BR Ambedkar: The Quest for Justice

[c]ourts granted injunctions to restrain members of particular castes from entering temples—even ones that were publicly supported and dedicated to the entire Hindu community. Damages were awarded for purificatory ceremonies necessitated by the pollution of lower castes; such pollution was actionable as a trespass on the person of the higher caste worshippers. It was a criminal offence for a member of the excluded caste knowingly to pollute a temple by his presence. (Galanter 1969)

The limitations of state law are apparent to Ambedkar as he notes:

The worst of it is that all this injustice and persecution can be perpetrated within the limits of the law. A Hindu may well say that he will not employ an Untouchable, that he will not sell him anything, that he will evict him from his land, that he will not allow him to take his cattle across his field without offending the law in the slightest degree. In doing so, he is only expressing his right. The law does not care with what motive he does it. The law does not see what injury it causes the untouchable. (Moon 2014: V, 270)

Combating Caste Discrimination through State Law

Even as Ambedkar was conscious of the limitations of state law, he saw in it a potential to begin attacking caste law. One principle of modern law which Ambedkar found of value was that law should be no respecter of persons. He referred approvingly to the provisions of the draft Penal Code and the commitment of the law commissioners to the principle that ‘[it] is an evil that any man should be above the law’ and their reasoning that the promulgation of the code was an opportunity to ensure that ‘the Code was binding alike on persons of different races and religions’ (Moon 2014: V, 103). It is clear that Ambedkar, very early on, saw the emancipatory possibilities of a universal law which applied to all persons as a welcome movement away from a law which differentiated between people based on race and religion. That was the strength of the Draft Penal Code.

Ambedkar also sought to draw on the principles of common law to assert the civil rights of the Dalits. After the famous Mahad satyagraha, in which the Untouchables drew water from Chawdar tank against caste Hindu prohibitions, the caste Hindus of Mahad filed a civil suit, making Ambedkar a party and seeking to assert their customary right to the use of the water in Chawdar tank as well as their right to exclude the Untouchables from the use of the tank from then on. For the caste Hindus to succeed in their claim they had to prove that the exclusion of Untouchables was a custom which was certain, existed from time immemorial, and was not against public policy.

Justice Broomfield (5) of the Bombay High Court, in his judgment in the case, held that there was no such immemorial custom and hence the caste Hindus could not exclude the Untouchables from the use of the tank. (6) He did not adjudicate the question as to whether untouchability was a custom which was against public policy.

Ambedkar expressed his disappointment at this judgment and its failure to address the question as to whether the custom of excluding Untouchables from the use of the tank was contrary to public policy. During the pendency of the litigation the court granted a temporary injunction against the Untouchables using Chawdar

tank, and the Untouchables under the leadership of Ambedkar did not violate the order of the court and go and drink water from the tank for a second time. According to Ambedkar, the strategic reason for suspending their civil disobedience was because

they wanted to have a judicial pronouncement on the issue whether the custom of untouchability can be recognized by the Court of law as valid. The rule of law is that a custom to be valid must be immemorial, must be certain and must not be opposed to morality or public policy. The Untouchables’ view is that it is a custom which is opposed to morality and public policy. But it is no use unless it is declared to be so by a judicial tribunal. Such a decision declaring the invalidity of the custom of untouchability would be of great value to the Untouchables in their fight for civil rights because it would seem illegal to import untouchability in civic matters. (Moon 2014: V, 252)

What is apparent in both examples is that Ambedkar was thinking about the possibilities and the potential of state law. It is true that state law, when it comes to combatting the millennial injustices of Indian society, lacks social legitimacy. As such it is a deeply weakened instrument when it comes to dealing with caste-base discrimination. However, in an otherwise totalitarian environment where all aspects of life are controlled by the rigid laws of caste, state law provides an entry point to begin questioning caste domination.

Dr Ambedkar asks whether, in a society with a deep-rooted majoritarian bias, the law can be mobilized to protect the interests of a geographically scattered minority? He argues that the coercive power of the law is a force which should be mobilized against the culturally and socially sanctioned prejudice of the majority community.

Sin and immorality cannot become tolerable because a majority is addicted to them or because the majority chooses to practise them. If untouchability is sinful and an immoral custom, then in the view of the depressed classes, it must be destroyed without any hesitation even if it was acceptable to the majority. (Ambedkar 2017, 109)

In the context of this majoritarian bias, the coercive force of the law must be mobilized on the side of right and morality. Speaking of the most insidious form of violence faced by the Untouchables, namely the social boycott, he cites the State Committee which concluded: ‘[T]his tyranny of the majority must be put down with a firm hand if we are to guarantee to the untouchable the freedom of speech and action necessary for their uplift’ (Jadhav 2013: I, 232).

The coming of Independence saw Ambedkar drawing upon this legacy of struggle to mobilize the counter majoritarian power of the law to first articulate the norm that untouchability was a constitutional offence, then to legislate the norm through the enactment of the Civil Rights Act, 1955. This Ambedkarite legacy was taken

forward through the subsequent enactment of the SC/ST Atrocities Act, 1989, and succeeding amendments.

Articulating the Norm of Untouchability as a Constitutional Crime

In a speech in 1930 at the First Round Table Conference, Dr Ambedkar first articulated the idea that untouchability should be considered a criminal offence.

First of all, we want a Fundamental Right enacted in the Constitution which will declare ‘Untouchability’ to be illegal for all public purposes. We must be emancipated from this social curse before we can at all consent to the Constitution; and secondly, this Fundamental Right must also invalidate and nullify all such disabilities and all such discriminations as may have been made hitherto. Next, we want legislation against the social persecution to which I have drawn your attention just now, and for this we have provided certain clauses which are based upon an Act which now prevails in Burma in the document which we have submitted. (Jadhav 2013: III, 126)

Sixteen years after the idea was first articulated by Dr Ambedkar, the practice of ‘untouchability’ was criminalized, with the Constituent Assembly passing what was to become Article 17 of the Indian Constitution. Article 17 reads:

Abolition of ‘Untouchability’

‘Untouchability’ is abolished and its practice in any form is forbidden. The enforcement of any disability arising out of ‘Untouchability’ shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law.

The debate in the Constituent Assembly was overwhelmingly in support of the said article (draft Article 11), with member after member seeing it as a new dawn. One such member, Shri Muniswamy Pillai, opined that ‘the very clause about untouchability and its abolition goes a long way to show the world that the unfortunate communities that are called “untouchables” will find solace when this Constitution comes into effect’ (Lok Sabha

Secretariat 1948, 665).

Also Read | Ambedkar and Democracy

[T]he fact is that we merely want to enact laws about it and expect the rural people to observe these laws. We must ourselves first observe the law for otherwise there would be no sense in asking others to act upon it. If we fail to observe it, it would be impossible to root out this evil. … [O]ur members act as fifth columnists in the rural areas, for they tell the people there that these laws are not in force and thus themselves act against the law. (Lok Sabha Secretariat 1948, 667)

A predominant sentiment in the speeches of both Shri Muniswami Pillai and Dr Manomohon Das is that the enactment of what was to become Article 17 meant that a practice which had defined Hindu society would no more be tolerated once the Constitution came into force. The amendment made untouchability a ‘punishable crime’, which meant that a law had to be enacted to effectively outlaw and punish a practice which was otherwise sanctioned by the society. However, the note of caution by Shri Santanu Kumar Das indicated that the key challenge would remain the enforcement of such a law which was avowedly counter-majoritarian.

The contribution of Dr Ambedkar was to the articulation of the norm on which all subsequent work with respect to ensuring the dignity of the Dalit community is based, namely that the practice of ‘untouchability’ should be considered a constitutional crime.

At the heart of Article 17 is a recognition of what Gautam Bhatia describes as ‘Ambedkar’s revolutionary insight: that the denial of human dignity, both material and symbolic, is caused not only by public power, but by private power as well—and the task of constitutionalism is not limited to satisfactorily regulating public power in service of liberty, but extends to positively guaranteeing human freedom even against the excesses of private power’. (7)

Articulating the Necessary Elements of a Counter-Majoritarian Law

While it was important for the Constitution to recognize the practice of untouchability as a crime, for this constitutional prohibition to have any impact it needed to find statutory expression. The bill which was moved in the Parliament to actualize this constitutional vision was the Untouchability Offences Bill in 1954. Dr Ambedkar’s responses to the bill in a speech that he delivered in the Rajya Sabha addressed the key question of how to legislate when the law is against the sentiments of the majority.

Dr Ambedkar began by making clear that he was uncomfortable with calling the statute the Untouchability Offences Bill and preferred the title Civil Rights (Untouchables) Protection Act. The reason for this was because the original title of the bill

gives the appearance that it is a Bill of a very minor character, just a dhobi not washing the cloth, just a barber not shaving or just a mithai-wala not selling laddus and things of that sort. People will think that these are trifl es and piffles and why has parliament bothered and wasted its time in dealing with dhobis and barbers and ladduwallas. It is not a Bill of that sort. It is a Bill which is intended to give protection with regard to Civil and Fundamental rights. (Jadhav 2013: I, 232)

Thus, the conceptual basis of the statute had to be clearly articulated—it was not dealing with ‘trifles and piffles’ but rather with ‘civil and fundamental rights’—and the legislation had to articulate a constitutional vision of protecting citizens from discrimination from their fellow citizens. Ambedkar said, ‘[U]ntouchability is not merely a social problem. It is a problem of the highest political importance and affects the fundamental question of the civil rights of the subjects of the state’ (Moon 2014: V, 139). (8)

To actualize this vision, Dr Ambedkar in fact argued that the statute should move away from the language of untouchability and move towards conceptualizing the offence as perpetrated on the body of the Scheduled Caste person. Referring to Shri Kailash Nath Katju, who tabled the bill, he said, ‘I don’t know why he should

keep on repeating Untouchability and Untouchables all the time. In the body of the Bill he is often speaking of Scheduled Castes. The Constitution speaks of the Scheduled Castes and I don’t know why he should fight shy of using the word Scheduled Castes in the title of the Bill itself’ (Jadhav 2013: 1, 231).

Dr Ambedkar then addressed the problems that had to be faced in enacting a law which, in its intent and character, was counter-majoritarian.

The first loophole that he pointed out was the compoundable nature of the offence which would ensure that the law remained a dead letter (Moon 2014: V, 236). He illustrated this point by referring to the Thakkar Bapa Committee Report on conditions of the Depressed Classes. He quoted from the report to make the point that

the Untouchables were not able to prosecute then [their] persecutors because of want of economic and financial means, and consequently they were ever ready to compromise with the offenders whenever the offenders wanted that the offence should be compromised. The fact was that the law remained a dead letter and those in whose favour it was enacted are unable to put in action and those against whom it is to be put in action, are able to silence the victim. (Moon 2014: V, 234)

The second loophole, Dr Ambedkar pointed out, was with respect to the question of punishment. The punishment prescribed was imprisonment for a maximum of six months or a fine. He was scathing on the question of the bill fighting shy of prescribing a punishment commensurate with the gravity of the offence. He observed:

My Honourable friend was very eloquent on the question of punishment. He said that the punishment ought to be very very [ sic] light and I was wondering whether he was pleading for a lighter punishment because be himself wanted to commit these offences. He said, ‘let the punishment be very light so that no grievance shall be left in the heart of the offender.’ (Moon 2014: V, 236)

What emerged through the discussion on the Untouchability Offences Bill, 1954, was the lack of seriousness of the government in bringing into effect a law tasked with combatting a deeply entrenched, socially and religiously sanctioned system of beliefs. The only person who seemed to grasp the nature of this enormous task was Dr Ambedkar.

What emerged so powerfully in the debate was the commitment of Dr Ambedkar to not just articulate the norm but also work on actualizing it. This meant working with the mechanisms of law and thinking through elements of procedure. When jurisprudence is meant to protect the interests of the oppressed it cannot just stop at norm development but should rather work with the technicalities of procedure to arrive at the best legislative

design. It is this combination of attention to norm development as well as legislative design that characterizes an Ambedkarite commitment to the deployment of law as a strategy to counter caste discrimination.

Footnotes

- Perhaps indicative of Ambedkar’s posthumous popularity was an Outlook poll on the most popular Indian after Gandhi; the winner by far was Ambedkar. See http://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/story/the-greatest-indian-after-gandhi/281103, last accessed on 13 June 2018.

- In this germinal article, Professor Baxi talks about seven Ambedkars, including Ambedkar the authentic Dalit, the exemplary scholar, the activist journalist, the pre-Gandhian activist, the constitutionalist, and the renouncer.

- However, this silence is beginning to be broken. See the recent works of Aishwary Kumar (2015) and Soumyabrata Choudhury (2018).

- Law, Hart points out, depends not only on the external social pressures which are brought to bear on human beings, but also on the inner point of view that such beings take towards rules conceived as imposing obligations (Lloyd and Freeman 1985, 406).

- Interestingly, Justice Broomfield was the same judge before whom Gandhi was tried for sedition.

- Narhari Damodar Vaidya v Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar [1937] 39 BOMLR 1295. Justice Broomfield held, ‘We therefore, agree with the learned Assistant Judge that the appellants have not established the immemorial custom which they allege. Had they succeeded on this point, it might have been necessary to consider whether the custom was unreasonable or contrary to public policy (though strictly speaking that was not pleaded in the lower Courts).’

- Gautam Bhatia (2016) argues that Article 17, Article 15(2), and Article 23 should be seen as a golden triangle: ‘Each of these articles protects the individual not against the State, but against other individuals, and against communities .’

- This insightful comment is still extremely valid if we consider the legislations which have been enacted to address the problems faced by those at the very bottom of the socio-economic hierarchy, namely those in manual scavenging. The two legislations are titled The Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act, 1993, and the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act, 2013. Both legislations in their title give little indication of the deep dignitarian harm caused by the caste-based practice of manual scavenging and the constitutional importance of the legislation; see PUCL-K (2019).