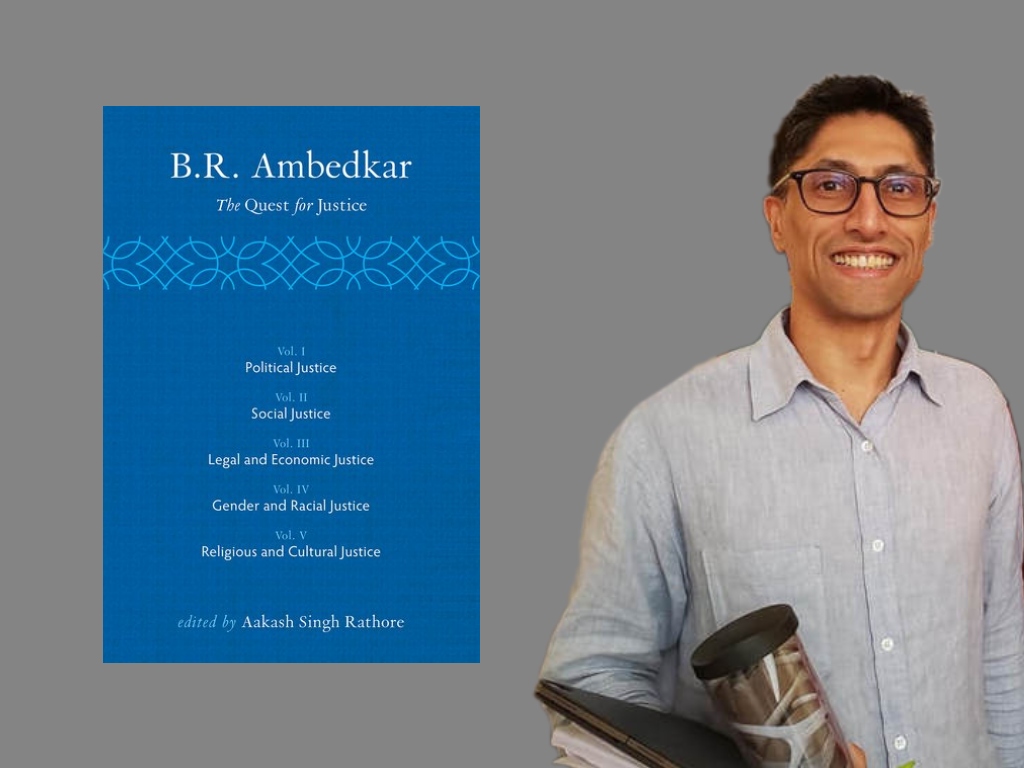

“Quest for Equity: Reclaiming Social Justice, Revisiting Ambedkar” was the title of an international conference hosted by the government of Karnataka in 2017. The five-volume Quest for Justice, edited by Aakash Singh Rathore, presents 54 papers selected from the more than 350 that were read at the three-day event. Taking in biography, history, law, economics and contemporary politics in India and the world, the volumes have been organised under five themes: political justice, social justice, legal and economic justice, gender and racial justice, and, religious and cultural justice.

In this conversation with the Indian Cultural Forum, Aakash Singh Rathore talks about The Quest for Justice, celebrating Ambedkar, the intersection of race and caste, and more.

ICF: The Quest for Justice volumes are a massive project, but they carry about fifteen per cent of the papers presented at the “Quest for Equity” conference of 2017. Given that equity and justice are near synonyms, are the books an encapsulation of the conference or a reframing? In what direction might the central theme have extended, had it run to further volumes?

Aakash Singh Rathore (ASR): The 5-volume collection, BR Ambedkar: The Quest for Justice, sprang out from the 2017 Ambedkar International Conference held in Bangalore, which was meant to celebrate the 127th Ambedkar Jayanti, and was called “Quest for Equity”. Now we are celebrating the 130th Ambedkar Jayanti, so if you do the math you see it has taken three years to bring these volumes to completion. Over the course of working on the books, they took on an independent life from the conference out of which they emerged. For one thing, they are more systematic and streamlined versus the 2017 conference, which was enormous (with participants numbering in the thousands) and branched off into so many directions — which is indeed what we wanted it to do, in order to be as plural and as inclusive as possible.

Also read | Ambedkar and Democracy

These books, however, all revolve tightly around the central theme of justice. Of course, justice is in itself a rich and textured concept with many layers, many meanings, and yes, even synonyms like ‘equity’ and ‘fairness’ and so on. What we chose to do was to focus on seven discrete but related types of justice: political justice, social justice, economic justice, legal justice, gender justice, racial justice, religious justice, and cultural justice. The first three types should be familiar to anyone given that they are recognized in the Preamble to the Constitution of India, which speaks of justice as social, economic, and political. One might ask, why did we not stop with only those three, then? But on the other hand, one might just as readily ask, why did we not go on to identify more? The answer to the latter is quite straightforward: because the list can conceivably go on forever. For, there are as many types of justice as there are injustice. Injustices, as we all know, are far from scarce.

ICF: Your Preface to the first volume begins by recounting Ambedkar’s life, where you remark that experiences of injustice create a different kind of knowledge from conceptual reflection. In a stark way, April 14 illustrates the contrast. Ambedkar’s birth anniversary in conceptual and ceremonial terms (he had revealed to Sharada Kabir that his date of birth was simply plucked from the air), it now brings us to the first anniversary of Prof Anand Teltumbde’s incarceration. The official celebration of Ambedkar pays no mind to ongoing local struggles. Does the global academic recognition of Ambedkar run a similar risk of abstracting him? Is there a danger that the immediate, empirical, improvisatory texture of political movements may lose him to institutional definition? How may non-activists, scholars and others, engage with Ambedkar fruitfully, as activists on the ground do?

ASR: Official celebrations may trivialise profound and organic achievements, but at the same time, they bring recognition and can also foster raised general awareness. So I think they have a positive side that ought not to be dismissed. Sure, Ambedkar’s birthday will be appropriated by anyone who can leverage it, from politicians to academicians, but at the same time, it has been and will continue to be authentically celebrated by the communities his life touched — those who say, ‘we are because he was’, and those who have been and will continue to be moved into action from his example and inspiration.

ICF: The conference of 2017 was organised by the Congress government of Karnataka, and Volume 1 of The Quest for Justice is introduced by Shashi Tharoor. Such a show of support is electorally expedient, after the decades-long neglect of Ambedkar. It is also a bid for the platform of social justice, using it to bridge the gap between Ambedkar’s denunciation of Hinduism and the Congress’s long-running refusal or inability to take his critique on board. Would you agree that there isn’t an institution in India today that can commemorate Ambedkar without sidestepping his position on caste and seeking to render him emollient?

ASR: Tokenism and electoral expediency and misappropriation, these are all real dangers, and will continue to grow as long as they continue to be viable or effective strategies. Beyond bemoaning them, in supplement to pushing back against them, there still remains a great deal of space for operating independently — it is up to us whether we take advantage of this space and act on it. The Indian Cultural Forum is a perfect example of this. There are other examples also in different areas, from academic centres to social work collectives. Official institutions will continue to project a domesticated Ambedkar, of course. Some of us who are working with or even within these institutions will take whatever steps we can to prevent too much decaffeination of his life, his teaching, his work. But the space where the radical and full-throated Ambedkar can thrive will always remain the wider social spaces, not the official institutional spaces.

ICF: Volume 3, Legal and Economic Justice, dwells on Ambedkar’s technical training, his contributions as a legal scholar and economist — the first trained economist among India’s political leaders. This is also where a wedge appears between Ambedkar as a statist thinker and his role as a social insurgent. As his biographer, do you see them in conflict?

ASR: My biography of Dr Ambedkar is tentatively to be titled The Passion of BR Ambedkar, because I want to show a fuller view of his personality — passionate and compassionate — instead of the so-often-repeated ‘life and work’ model, or the standard intellectual biography. When we see Ambedkar’s life through a personality-driven narrative, it starts to become impossible to sustain the statist Ambedkar. Examples are wide-ranging, such as his (very little known) contemptuous remarks against the Madras High Court following upon their decision dismantling reservation. And indeed, even the very speech wherein we first hear Ambedkar’s appeal to leave aside practices like dharnas which are the very ‘grammar of anarchy’, no one looks at very strong remarks he makes earlier in the same speech about Thomas Jefferson’s views on limitations of a previous generation binding a succeeding one (‘the Earth belongs to the living’).

Also read | The power of counter-ritual

Jefferson’s position has been well encapsulated in his famous ‘tree of liberty’ remarks: ‘what country can preserve it’s liberties if their rulers are not warned from time to time that their people preserve the spirit of resistance? …The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is it’s natural manure.’ Speaking of Jefferson’s view on succeeding generations needing to free themselves from the constraints of earlier ones, Ambedkar says: ‘I admit that what Jefferson has said is not merely true, but is absolutely true.‘ Jefferson was of the view that a constitution was only basic law insofar as it reflected natural rights, and that the rest of it was more positive law, akin to legislation. This is a very radical and non-statist, non-orthodox kind of viewpoint, one that led to people quoting him as suggesting that every generation needs a new revolution. While we cannot easily attribute this much radicality to Ambedkar’s own view, it is still very interesting that Ambedkar chose to use that expression, ‘what Jefferson has said is not merely true, but is absolutely true.’ That is a great deal of emphasis on a revolutionary point. And Ambedkar says this only minutes prior to him speaking against the ‘grammar of anarchy’.

ICF: How much further since 2017 has scholarship on the intersection of race and caste travelled? How significant is this for the social sciences? Where do you see Ambedkar emerging in this new framework?

ASR: A very brilliant sociologist from Mumbai, Varsha Ayyar, has suggested that Isabel Wilkerson’s recent best-selling book on the race problem in America, entitled Caste: The Origin of Our Discontents, has dropped race for caste as a superior tool for understanding the tenacity of inequality, hierarchy, prejudice, and so on. Wilkerson’s book, of course, spends considerable time discussing Ambedkar. This is just one prominent example of what I believe evidences a much more widespread phenomenon. That is, how Ambedkar’s systematic insights are increasingly becoming useful throughout the post-colonial world and the Global South, as well as in the developed, highly racialised societies of the USA and UK. Dr Ambedkar offers a uniquely egalitarian and holistic vision, the likes of which had been largely drowned out in the many libertarian movements of the 20th century. Pushes for freedom without equality have served to liberate some but always at the expense of others. The 21st century will in many ways belong to Ambedkar. Not just locally, in cultural celebrations, or nationally, in social movements, but globally, as the world discovers the depth and promise of his egalitarian vision, always seeking justice. What I tried to do with the new 5-volume collection, BR Ambedkar: The Quest for Justice, was to facilitate in a small way this discovery which I believe to be inevitable.