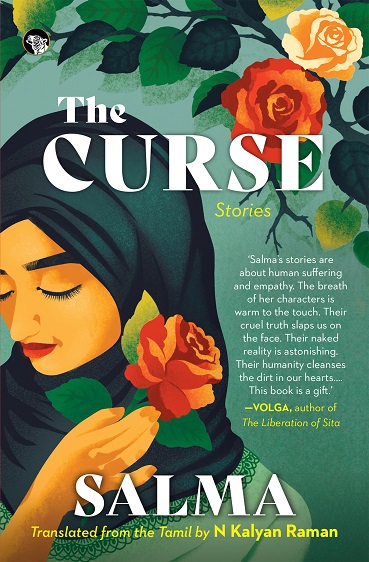

In The Curse, translated into English by N Kalyan Raman, acclaimed author and poet Salma blasts through the artifice of genre and language to reveal the messy, violent, vulnerable and sometimes beautiful realities of being a woman in deeply patriarchal societies.

Loosely rooted in the rural Muslim communities of Tamil Nadu, these stories shine a light on the complex dramas governing the daily lives of most women moving through the world.

The following is an excerpt from the story “Black Beads and Television” of the book.

From six-thirty in the evening, women and children from all the houses in the street began to invade their house. Regardless of whether they understood the programmes or not, whether the picture was clear or not, the crowd did not get any smaller. Mahmuda, who in the initial days had proudly welcomed her relatives, served them tea and played hostess in general, started wondering why her husband had brought this wretched TV. When Chitrahargot over after eight and the crowd dispersed, she would grumble to her heart’s content as she swept up the sand brought into the house by the visitors’ feet. As far as she was concerned, the television had become a burden that outweighed their pride in it. Shaukat felt pity when he saw her doing these chores. Zakiramma from the neighbouring street was the only one who stayed back to help Mahmuda with cleaning the house.

Even if on occasion Mahmuda gave ten or twenty rupees cash in her hand, Zakiramma wouldn’t accept it. ‘No need,’ she’d say. ‘Don’t I watch your TV for free? Then why should you pay me?’ In the lone cinema theatre in their village, they changed the picture every week. Zakiramma would always be the first person at the opening show. She was fifty-eight and crazy about cinema.

Highly annoyed at her ways, her husband Sultan would vent his anger out loud. ‘Look at her, thambi. Does it look proper when a woman of good family, a Muslim woman, loiters around? If there is an MGR film playing, she watches it every day. She is burning up all the money I earn by carrying loads,’ he would protest.

‘Yes. What about it? I’ll go when I want to. I love MGR movies like my own life,’ Zakiramma would reply.

‘You whore…Gruel is all you eat and you want rosewater to rinse your mouth, do you?’ Sultan would yell at her. Mahmuda and Shaukat Ali had to listen to their quarrels all the time. Mahmuda told her husband one day: ‘Look at this Zakiramma wiping our TV set, see how lovingly she does it. The way she keeps patting it, I hope it doesn’t get damaged in the process.’ At times, she would follow Zakiramma on her way home, pick up some dirt from any spot trodden by her feet, mix it with salt and seven dried chillies, and along with twigs from the roof of their house, perform a ritual over Shaukat and the TV positioned next to each other, in order to ward off the evil eye.

‘You have to do this too?’ Shaukat would mutter to himself.

If Zakiramma had watched a film the previous night, she would, while cleaning the dirty dishes the next morning, narrate an elaborate analysis of the plot. The listener would feel as if they had seen the film themselves. Barring one or two women, no other woman went to the theatre to see films. No matter which film, Zakiramma would conclude her experience of watching it in a single word: laddu. All cinema was sweet and delectable to her. In her view, there was no such thing as a bad film.

One day, when Shaukat Ali happened to remark, ‘That film was just no good. I also saw it yesterday,’ Zakiramma retorted: ‘Why, bhai, think about the amount of money they would have spent to make this film and how hard they must have worked. Is it fair that, after paying only 35 paise to watch it, we trash the film as garbage? That’s why I will never say that a film is bad.’ When Zakiramma said this while meticulously wiping the dust off the TV set, Shaukat Ali laughed, mostly to himself.

Mahmuda noticed that Zakiramma’s eyes seemed to float in a dream-like state. At times, she would call out the old woman, saying, ‘What’s with the deep thought when you still have work to do?’

‘It’s nothing,’ Zakiramma would say and resume her task.

Over the past fortnight, after Tamil programmes on Chennai Doordarshan began airing on their TV, Zakiramma rarely ever went home. She was unable to sleep a wink these days. ‘Why should I go to the theatre to watch a film? Why can’t I bring the film home, like in Mahmuda’s house?’ She began to dream.

‘If television can be installed in a rich household, why can’t it be put in mine, too?’ she mused. The constant brooding began to hamper her work.

Her activities were reduced to passing her days in deep thought. All kinds of plans were being constantly worked over in her mind. Whenever her eyes, wrinkled from a lifetime of washing utensils, fell on the glossy smoothness of the television set, she was transported to delight and pleasure. She began to develop an intense disdain for her life without a TV. More than the lack of good clothes to wear, jewellery, a house or children, it was the lack of a TV that was eating into her. It was more pleasant to think of the TV as an essential rather than unnecessary item in the household. It seemed as though she had entirely forgotten that she was living with an old man called Sultan.

Since Zakiramma hadn’t turned up for work till noon on that day, Mahmuda went to her house looking for her. She could hear Sultan’s screams even from outside their home.

Since she knew that such quarrels were nothing unusual between the couple, Mahmuda pushed the tin door open and entered. The screech of the door’s hinges drew Sultan’s attention, which fell on her.

‘Come in, Amma. Will you look at what this woman has done?’ In the corner where Sultan was pointing, she found a large television set next to a cardboard carton. ‘Why do we need this? This useless woman has paid 4,000 rupees and bought it.’

Mahmuda blinked, unable to understand. A television set for four thousand rupees? How had Zakiramma come by so much money? She looked over at Zakiramma in confusion. She was seated majestically on a low wall abutting the kitchen. It seemed as though she hadn’t heard a word of Sultan’s outburst.

Zakiramma was gazing exultantly at the TV in front of her. Mahmuda thought that she might be wondering whom she could request for hosting the antenna.

‘Do you know where the money came from? She sold her chain of golden beads. When I ask her, she says a string of plain black beads will do. Whom do I complain to about such travesty?’

Ignoring Sultan’s fury, Zakiramma said, ‘Why does he insist on hanging around my neck only as gold? What’s wrong with plain black beads?’

Before her gratified desire, Sultan’s wails came to nothing and faded away in the wind, even as Mahmuda watched in wonder and amazement.