Deepa Dhanraj’s Ye Kya Hua Is Sheher Ko? (1986) pioneered a kind of documentary filmmaking that developed more distinctly over the coming decades with a host of films by Anand Patwardhan, Rakesh Sharma and the likes, which presented painstaking autopsies of communal violence. Covering the communal tensions in Hyderabad in 1984, the 95-minute documentary can be said to be prophetic in the way it tugs at early signs and strategies of mobilisation along communal lines, the ascendance of Hindutva ultra-nationalist tendencies in political formations, the apathy and inaction of state machinery during communal tensions, the impact of violence on not just people’s lives but also its aftermath and its deeper repercussions for livelihoods and economy, and in the way it thoroughly discredits the narratives of riots as spontaneous acts of violence as opposed to planned politically motivated manoeuvres using interviews, conversations, and speeches

The film after being shot, took another year in the course of editing, and yet another in overcoming censorship. Finally released in 1986, the documentary did countless screenings across India which subsequently damaged the film. It got a new lease of life when it was restored in 2013, after the efforts of historian Nicole Wolf and the support of Arsenal Institute for Film and Video Art’s Living Archive Project.

Dhanraj’s work spans across issues of caste and gender with several acclaimed documentaries like Something like a War (1991), Invoking Justice (2011), and We Have Not Come Here to Die (2019). Unfortunately, while after over thirty years, Ye Kya Hua Is Sheher Ko? continues to be relevant to our times, in the context of the Hindutva forces now governing at the centre, the consequent violence in North-east Delhi, the Ram-mandir issue, CAA-NRC and the opposition to it, Dhanraj’s most recent work We Have Not Come Here to Die ties the issues of caste oppression firmly with the ugly reality of Hindutva politics.

Aparna from the ICF team spoke to Dhanraj about making Ye Kya Hua Is Sheher Ko?, standing witness to violence, transcribing it as a filmmaker, telling the story in alliance with the oppressed, about proliferation of images and the challenges of documenting in the present times, and more.

Aparna: One of the things that really struck me about the Ye Kya Hua Is Sheher Ko was the strong emphasis on looking at the political situation historically. Can you talk about the specificity of Hyderabad as a city and its history, in the context of these riots and your documentation of them?

Deepa: Just to give you a bit of background, Hyderabad is my city. I grew up there. So, there is also a very strong personal connection to the city. I had known many people as friends, who were very active in the city, particularly in the old city for a long time.

In 1978, we saw the first kind of communal clashes between Hindus and Muslims in the old city. At that time, there was a lot of discussion on what could be done to start a conversation between the communities and bring them together. The group that had started to do this called themselves “Hyderabad Ekta”. Many of them were academics and human rights defenders or civil rights activists. There were political people and some concerned citizens — a very mixed group. The only thing I think that could uniformly define them was that none of them had any political party links. So, I was aware of these conversations, these meetings and that people were trying to get together trying to create activities and platforms, where people from both the communities could come and meet in a non-hostile space and talk.

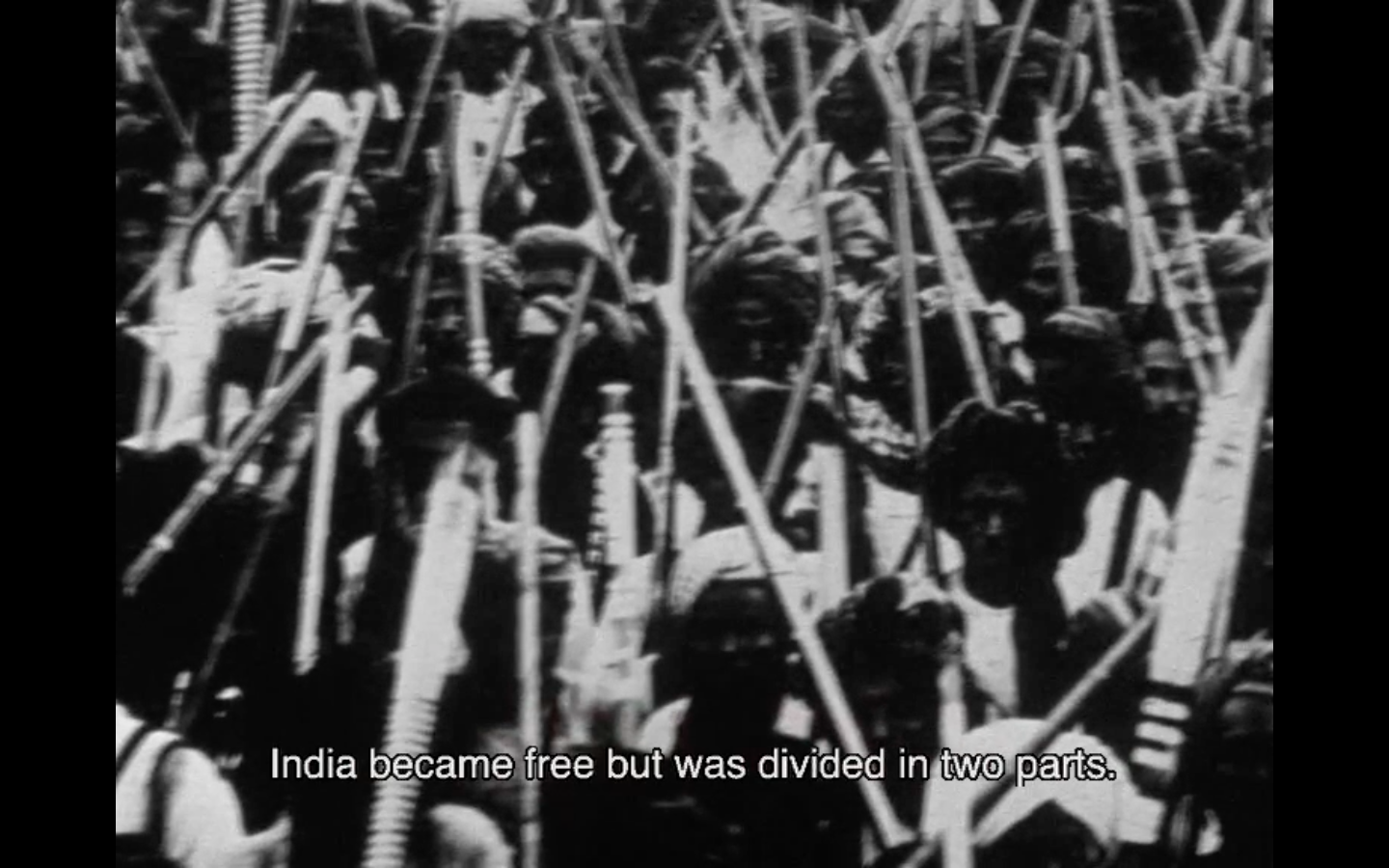

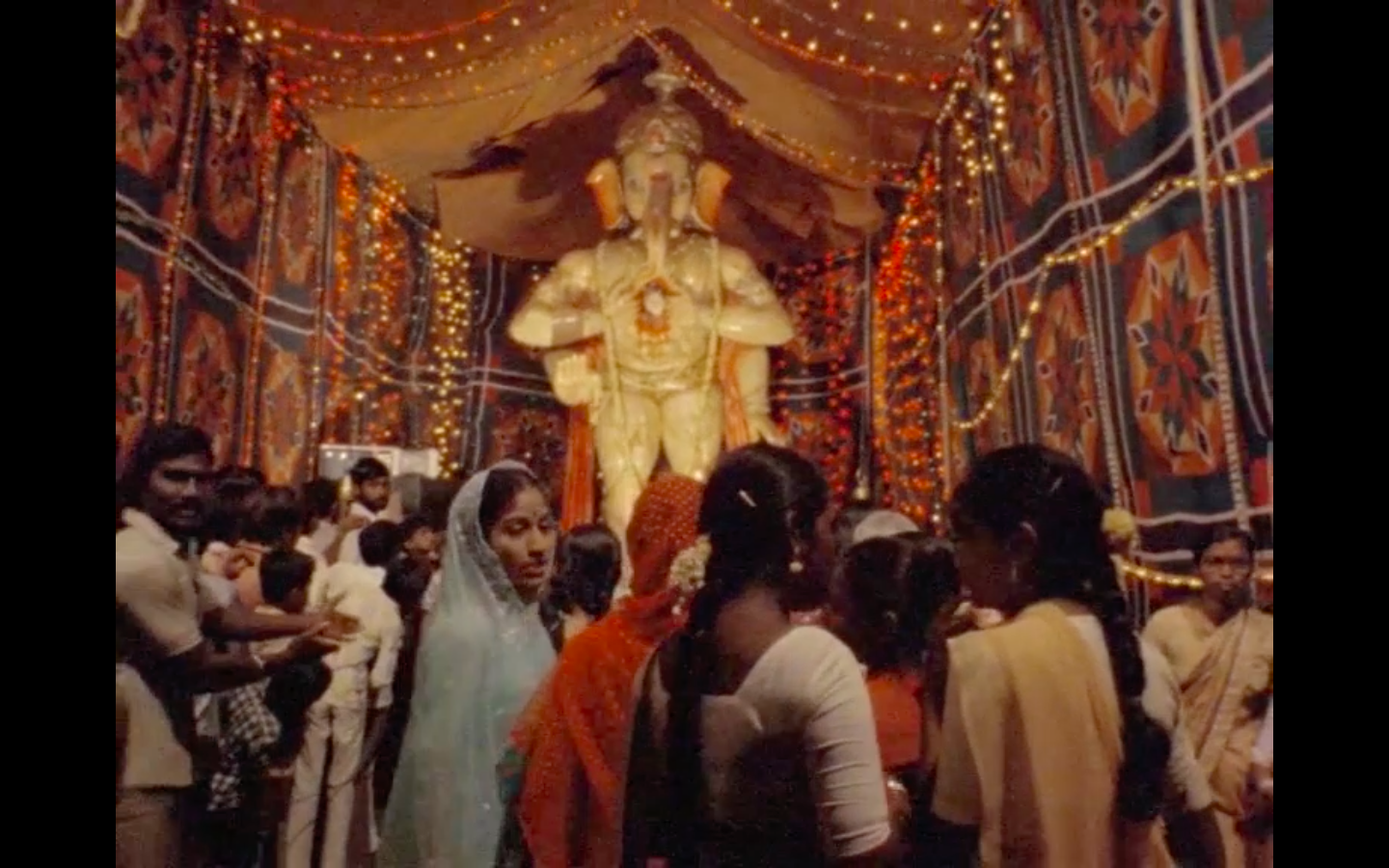

Then the Ganesh procession started. This was something completely new in Hyderabad, because earlier it was a very personal pooja people did it at their homes, with very small idols which were taken to be immersed. This would be done by families or maybe in one mohalla. There was nothing institutionalised about it — neither the celebration, nor the emotions. But what we saw in the early 80s was a kind of mass mobilisation. We saw massive murties being made, where Ganesh was recast in a very militant form and these idols were displayed publicly. They were out on the streets. A lot of extortion went on, money was collected to put these up, and on the final day, when the immersion would take place, lakhs of people, mainly young men, would be out. What always followed tragically was rioting and people getting killed. This had not happened before.

So, the conversation arose between Hyderabad Ekta and us, if we could try and find out what was attracting young men to these formations. Why did they want to be a part of these activities? Of course, after the film was shot, after the two and a half months of being there — listening to people about their memories of the annexation of the Hyderabad state, the kind of formations that were there like the original Majlis-e-Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen and its origins, who the Razakars were, what the Arya Samaj was doing with Hindus in the area — we learnt that there were people at the time in the old city for whom these memories were still very fresh. So, when it was the time to actually edit the film and put it together, I felt that we needed a historical context; we needed to know that this was not something that had its roots in 1984 alone. We had to link it to earlier events.

I think it’s very important that we continue to do that. Every riot is to be looked at in its particularity. I don’t think we should generalise in any sense, because each situation, each political context is very particular. The only thing we can say with any certainty is that very often, these are not spontaneous. People don’t just get up irrationally and decide to attack each other. There is always some kind of machination — there are events and then there are background actors. What I would say about Hyderabad’s situation in relation to the film, is that I think for us, it was very clear that we wanted to look at the “autopsy” of the riot — who was doing what, who was profiting, who were the victims on the other side, and what was this very cynical use of the law and order situation; and the fact that there were institutions, for example, like the police or the judiciary, that really did not act. I think it was the first time, at least on film, that this kind of an approach to what would normally be called a “communal riot” was taken. We looked at the very particular political and historical circumstances that enabled it to happen.

Aparna: Women’s bodies have always been sites of communal violence. Ye Kya Hua… doesn’t talk about that much. Did sexual violence not take place during the riots you shot? Or was it a conscious choice to not show it? Also, as a woman yourself, in the middle of this communally tense and violent situation while making this film, I was wondering if you ever felt threatened by something like that?

Deepa: During the 22 days we filmed, we didn’t hear stories about sexual attacks.

Personally, if you’re asking me, you have to imagine that even when we were shooting the juloos on stage, or when we were watching things burn around us that night, I was the only woman there with Navroze. Strangely, I wasn’t afraid when I was in Muslim processions. There were all these young men, but I never felt afraid. In fact, there was a way in which they made room for us to walk off and out.

But during the Ganesh procession, yes, I was very afraid. You just felt like anything could happen here. I think I have to say that much more than fear, for me personally, it was just trauma and horror. I mean, you come up on a situation hours after, half an hour after, an attack. That’s really something you can’t get over. You know, where actually to be killed with a knife is merciful. You look at the objects that they were using to attack each other— whether it was stones or just anything.

And then, you have to be that young also, and foolhardy. Because it would not have been surprising if we had been attacked, because what were we doing there in this curfew zones? Who were we and why should we why should we be given any special treatment?

Aparna: You also speak to the political leaders involved in fostering these communal conflicts. Can you talk about those conversations?

Deepa: It was important to talk to the leaders. What you see in the edit is only linked to things like why the Ganesh procession started, what was its utility, about the city – generic questions. But we also spoke about the political situation: why is the Majlis aligned with the Congress party and why is BJP aligned with the Telugu Desam, isn’t that what is causing this conflict, do they not see that it is actually fanning the flames, and so on. As far as the film goes, these are the two main parties who control the conversation on communal politics. Not only do they control the conversation, but the cadres who are deployed to create violence. So, it was very clear that one had to speak to them.

In those days, they were still very sophisticated and careful about how they spoke about the other community, it wasn’t so crude; at least when they were talking to camera. But that was one persona. In the film it worked for us because, we needed that in the one-on-one interviews, and then we contrasted it with what they said on those platforms and podiums, how they connected with their constituencies, the kind of language they used there, how they presented themselves there — these two things also made a made a good contrast. I think it is useful to have these two articulations of the same people.

Aparna: How did it compare with the experience of talking to people who were affected? As someone interrogating the scene, how did you position yourself differently?

Deepa: With the politicians, the way one presents oneself as well as the questions are very different. It was much more formal, more like an interview. There is also an expectation from them as to where they’ll be seated – for example, “Tiger” Narendra and his tiger, his office, and the way he wants to present himself. It is a very different context and conversation. If you want the conversation to go on, you have to be calm. I mean, you can’t afford to get kicked out after the first question. You have a certain idea in your head as to what you expect, what you hope will come out of this interview and you have to keep at it. They were both very sophisticated about what they would reveal and not reveal. You had to know how to pick up their hints, commanding to not go any further with a topic of conversation, but move on to something else instead.

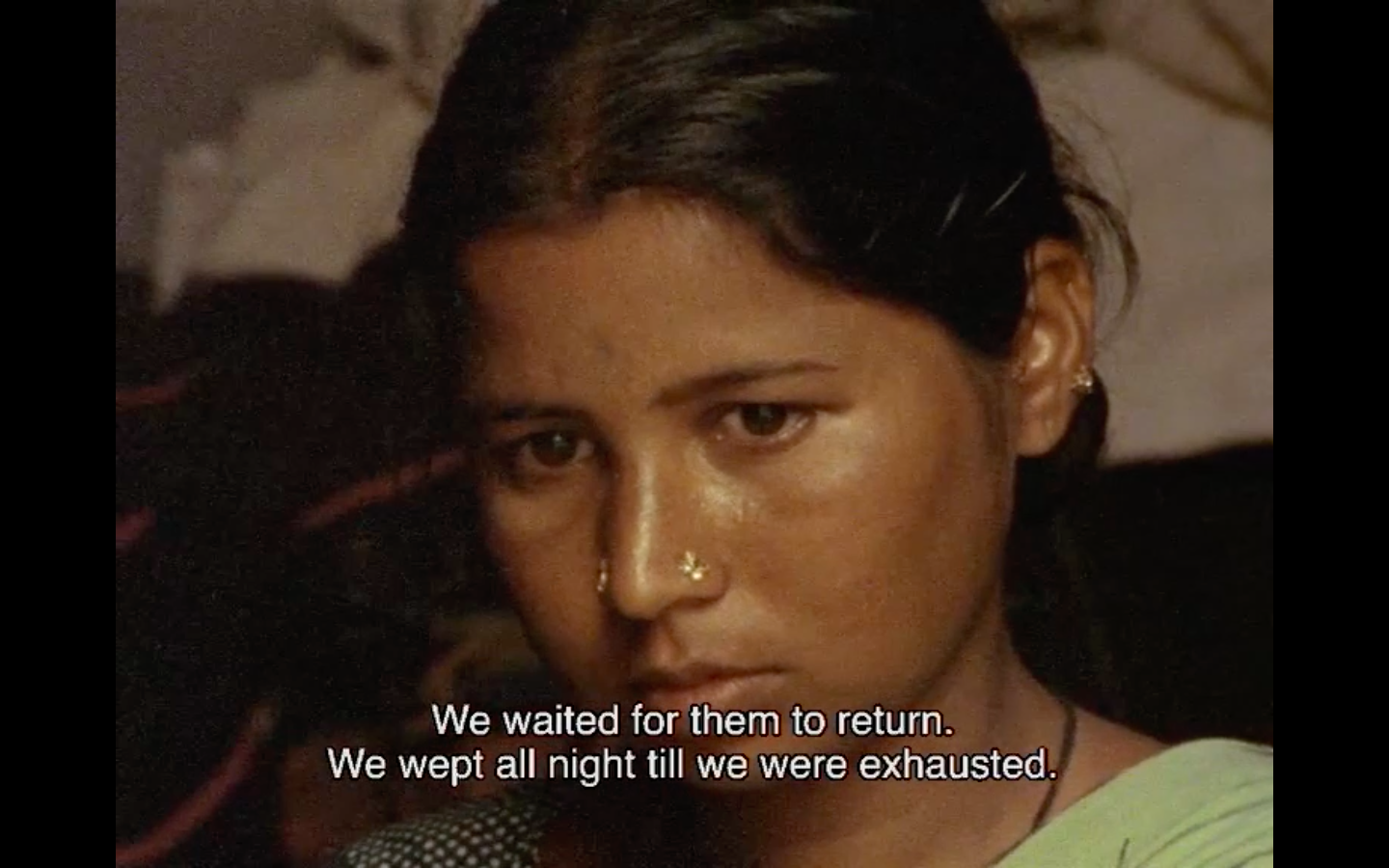

Whereas with people who have been affected, it was very traumatic and painful. One had to be mindful to not create a voyeuristic spectacle. You had to connect with them, people had to be able to present themselves with what they were feeling and what they’d been through. Amongst ourselves, we talked a lot about how we would do this. So, one way was that you had to give people time to speak. It was not an interview. It was just about listening, and how much compassion one can bring to that moment. It’s a kind of human interaction. When we have to think about that and how to achieve that cinematically, I think one thing we decided was no close-ups, allowing a really long take, their silence and pauses, and no changing of the image size. If you look at it in the film, the way it works is that while we’re honouring what they’ve been through and listening to them, it’s also very calm. It’s not an agitated “I’m going to zoom in further for that dramatic effect.” There is something still about it.

Aparna: One starts with a project with a certain expectation of it and often it takes you somewhere else. And I think that’s a good thing, right?

Deepa: Yes.

Aparna: So, I was wondering what those surprises were for you? Can you speak about that whole process?

Deepa: I think this and We Have Not Come Here to Die are two of the hardest films I’ve made. You have something in your head, but every day you’re shooting, and what you come back with overturns what you had thought the film would be. You have to reconceptualise all the time. Be open enough to say I don’t know what something is, but it may link to something else. You have to have huge cinematic reflexes, because stuff is happening all around you. So, there is really no room, in a sense, for long detailed conversations as to what the cinematic strategies are going to be because, you get there and have to start shooting.

In those days, it was so difficult to even make a film. I don’t know if people realise the stress of making a film on actual film. There’s this anxiety that you have to tell it all because you’re not going to get another chance, so you pack it with everything, you bring in as many angles, as many questions. We were shooting on 16m, you can’t even look at the footage until it goes to a lab. So, it’s just what you saw and what you thought. I’d ask Navroze about the lens, the frame and then talk about it. One had to come up with these kinds of strategies, think on your feet.

Today you work on digital and can shoot for hours. Download it on your laptop, go back and shoot again for hours! In those days, film was so expensive, and one reel was only 10 minutes long. You had to make sure how you were going to use that – economically, and in every other sense. So, there were tremendous material restrictions defining the process — not just cinematic strategies and ethical political choices. It was also the material nature of what filmmaking was in those days.

So, we shot for 22 days. We thought, let’s just go in there and see what we can find. But the edit was very difficult — it was almost nine months of many versions and trying to struggle with this material, because of course, when you shoot like that, if you have three or four ideas that you’re pursuing, then you don’t get clean narratives.

When we first set out to make this film, it was not this film. It was something that Hyderabad Ekta wanted that they could use to enable conversations between communities. So, we started with filming the Ganesh procession, and then this riot erupts in front of our eyes. Meanwhile, the political situation in the state was very particular, because there was this coup of sorts, supported by the Congress, against NT Rama Rao, when he went off to have a surgery in the US. At that stage, it occurred to us that we should try to find out how the riot took place and who the actors were. So, we followed that track for a bit. Then simultaneously, as we were doing that, we realised the implications of the curfew for the people in the city. Why were the deaths and stabbings continuing? So that took us off in another direction. Basically, the consensus was that we would just film. The film as such, therefore, was really made on the editing table. One went back, looked at the material, and then said, “okay, what are we going to do with this?”

We still had to honour the agreement with Hyderabad Ekta, which of course, I was also in agreement with — that the film needed to be useful for the community. It needed to go back and help in starting conversations. That was still a big priority. The ideas, as I said, would change every day, because suddenly, you’ve got some more of Bhaskar Rao, then you got a little bit more of what was happening with certain victims, and then you got you got something about what was happening in the assembly, and such. So, it I think it’s about just being open and filming what you can.

Aparna: Your documentaries are really a critical enquiry. What do you think are the challenges for people pursuing work like that in the present political context?

Deepa: People are still working and filming. I just heard that some were shooting at even around the Delhi riots and then there was the Muzzaffarnagar film by Nakul Sawhney.

But what’s different these days is that everybody is shooting all the time. Images are proliferating and I call it a “tsunami of images”. Facebook and WhatsApp are full of videos. So I think today, the challenge for myself as a documentary filmmaker — if you are trying to do something around a public event, which has been the subject of TV debates, social media discussions, for which already a lot of images are available and people have seen them, and maybe your own camera is in that forest of tripods — would be “what my intention is.” How am I going to unpack what I want to particularly bring out? What propels you? What can people see of my approach or how am I looking at this? That is the key.

In each case, you first identify with what your starting point is. You ask yourself, “why do I want to make this film?” All my films are always in “alliance with” either a community or certain politics. And I always see this as a circular loop where I hope the film can return to. Once that is clear, you can then start working with the material available. In all of that, there are choices that indicate the politics of being in an alliance with something.

Aparna: Yes, I did notice that in all your films that there is always a juxtaposition where, as you mentioned, you’re in an alliance with something and so we’re drawn into a certain intimacy with that entity or community. Whereas, what is opposed to it stands always slightly inaccessible. That’s why I was interested in the difference between talking to the political leaders versus talking to the affected in the first film. I did notice this wonderful scene in which was to me a distillation of that alliance. It’s a shot from the door of house while in curfew, where you see the police vehicle passing outside. It really, quite precisely locates where you locate yourself- both physically and symbolically. In Something Like a War you offer a very stark contrast between the intimate conversations of these women, how they are sitting and talking so personally with each other, contrasted to the alienating spaces of the hospital, the doctor talking somewhat indifferent to the camera. Then again, in the film about Rohith Vemula, We Have Not Come Here to Die, the difference was that while those who were involved on the ground spoke directly into the camera, the leaders would often be seen only on the TV. And although these choices in image-making aren’t the same across 25 years of your filmmaking, there is a very clear statement of alliance. I think that’s a very heartening aspect of watching films that you’ve made. Thank you so much for talking to ICF with such generosity. We look forward to more conversations with you, and films from you in the future.