Based on work by Project 39A, this book emerges from the interviews with nearly 400 prisoners sentenced to death and their families, done for the Death Penalty India Report, 2016. Capturing the “the sense of expectation, the stark hopelessness and the cruel reality of incessantly anticipating one’s own death”, the book brings to the reader a grim confrontation with reality of people who continue to be defined by their crime and little else. Dehumanised by the state and society alike, personal narratives of death row prisoners, raise questions on death penalty as a punitive measure, and all that it entails for the ones condemned and their families.

The following is an excerpt from the book.

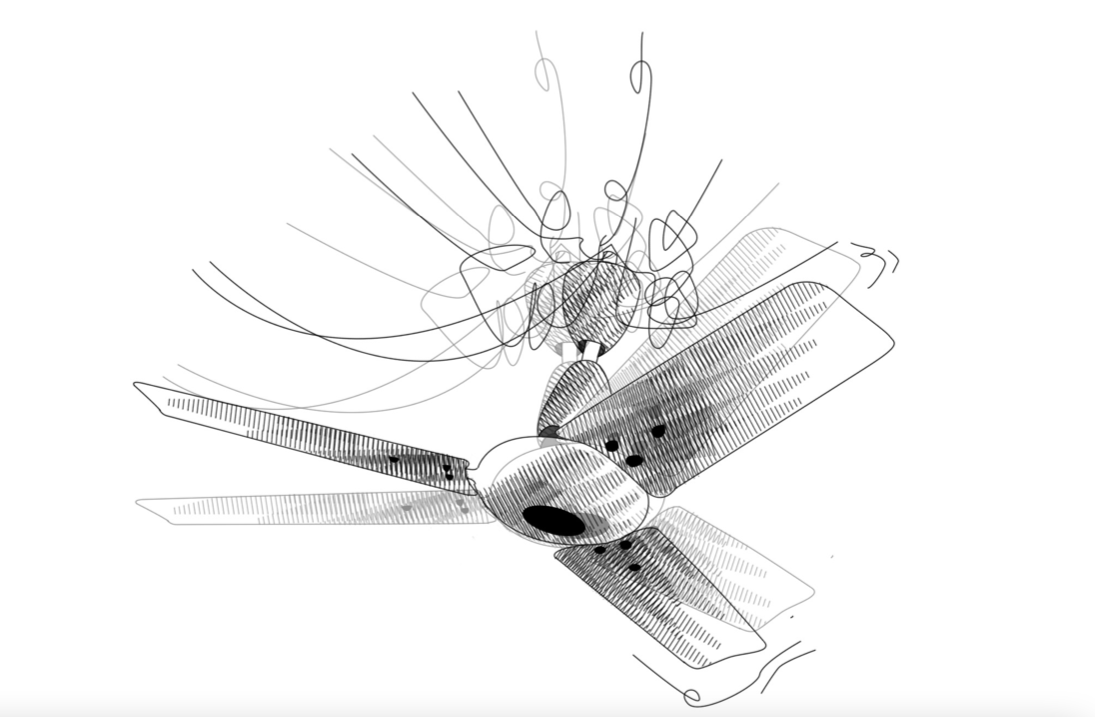

The fan was so slow and squeaky that at times Jameel Qureshi could only hear its swishing and swooshing, instead ofthe arguments presented by the lawyers. He had to really strain to listen and to understand things, and even then hemanaged to miss many important points. There were moments when his brain would get so overwhelmed that itwould involuntarily focus on the sounds of the fan.

These moments lulled him into a stupor.

Drifting into oblivion was easier than fighting, but he forced himself to pay attention – not so much becausehe wanted to escape the death penalty, but because he wanted a chance to speak, in case it was allowed. He wasalmost beyond the fear of death now. All he wanted was a chance to talk, and he got it in the end.

‘May I please say something before the judgment is pronounced?’ he asked the judge, ignoring hislawyer’s apprehensive glances.

The judge took off his reading glasses. He looked at the defendant and said, ‘I am obliged to let you speakunder statement 313. Go ahead, what do you want to say?’

‘Thank you, sir,’ Jameel said, adjusting his black shirt and clearing his throat. ‘I just want to say that thepolice dragged me from city to city. They tried me for previous charges and current charges, and scrutinizedthe record of every person that I have ever met to try and form a good picture of future charges. I know you willsay that it is good policing, but how does it justify all the times they made connections where there weren’tany, just to prove their own preconceived theories? The fact of the matter is that the police does not like me,so here I am standing in front of you for a crime I have not committed.’

The judge was not impressed. ‘Mr Qureshi, state clearly whatever you want to say in your defence.’

‘But sir, how can I defend myself in a situation where scrutiny has turned into narrow-minded obsession?The police worked hard on this case, but their work has not been completely above board.’

‘Do you understand what is happening here?’ the judge asked. ‘Farrukh Siddiqui confessed to planning theattack and took your name in relation to the said attack.’

‘The police arrested many of us, sir. Farrukh was the only one who confessed. And that was not because hehad anything to do with the attack, but because we were badly beaten up by the police. He probably could not take it anymore,’ said Jameel Qureshi.

‘Your lawyer has gone through all of this with us, Mr Qureshi. The fact remains that there is no evidence thatthe confession was made under duress,’ the judge stated.

‘Is it okay then for them to have pointed a gun at me and ordered me to confess? Is it okay for them to havedenied me a lawyer during the interrogation? They even harassed my family and warned my sister against visitingme,’ Jameel blurted out.

‘Do not lose your cool in this court. There is no proof of any of this. I think you should stop talking if you’vehad your say,’ the judge said, putting his reading glasses back on.

‘But,’ Jameel burst out again, ‘all the proof and evidence that was produced during these hearings was only whatthe police wanted you to see, sir. Early in the interrogation, they had asked me to hand over my watch. A fewmonths later, I saw it being produced as evidence. They even made me sign a blank paper once.’

‘The police did its job, Mr Qureshi. Do not undermine the impact of that attack on the national conscience,’said the judge sternly.

‘But then what is the difference, sir?’ Jameel Qureshi asked, his desperation becoming more and moreapparent. ‘What is the difference between those who are criticized for killing innocent people in the name of politicsand religion and the police? How are their actions justified? I have not only seen them planting false evidence, but also torturing innocent people. Is that okay just because it is for the benefit of national defence?’

‘You have the gall to compare the police force to terrorist organizations?’ the judge almost screamed.

‘No sir. I am just telling you what is in my heart. I have only had some basic education, so I might not besaying the right things. But I am able to say what I want because I have nothing to lose; in any case, I will probablybe hanged or kept in jail for a long time. There is no sense in being afraid any more. I also want to add, sir, thatthere are many rules and regulations, but nobody really follows them.’

The judge quickly wrote something on the large book in front of him, and got ready to pronounce his judgement.

The sound of the fan started to seem loud again, and Jameel let his mind focus on the lulling swishingand swooshing. He had said what he wanted to say, nothing else mattered anymore.