Home to the largest number of undernourished people on the planet, India imposed the world’s harshest lockdown for the pandemic. A country that has not been releasing data on health and nutrition since 2014, publishes no reliable figures on urban daily-wagers, and was already in its worst crisis of unemployment since Independence, now pushed the poor to the edge of death. Migrant workers in India’s cities received a pittance in their Jan Dhan accounts, were mostly locked out of the PDS system, shortchanged and abandoned by employers, assaulted by the police, conveniently overlooked by the media, middle class and judiciary. It was a crime against humanity.

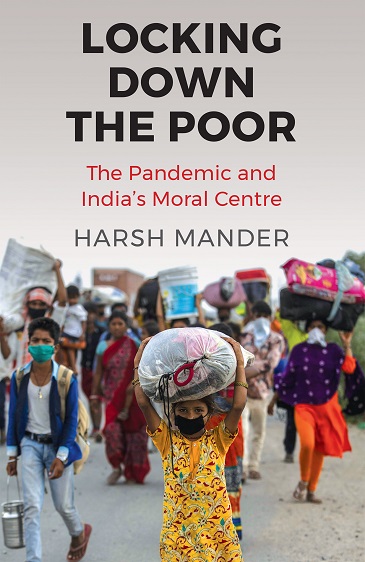

In Locking Down the Poor: The Pandemic and India’s Moral Centre, Harsh Mander collates fact after damning fact from this period, along with many individual stories, showing how state institutions stripped India’s poor of their political rights and dignity, and emptied the republic of any moral content.

The following extract is taken from the chapter “The Migrant Road: How Far Is Home?”

The central and state governments offered no relief of any kind to the workers on the road. In fact, they did the opposite. When some senior IAS officers in Delhi organized buses for migrants who wanted to return, they were reprimanded, suspended and removed from their postings.40 Many migrant workers reported being beaten like fugitives from the law by the police. In mid-May, more than 500 migrant labourers from Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha and other states were assaulted by police in Vijayawada. They were returning from establishments that had shut down in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh when they were stopped on the highway by the Andhra police and told to go back. When the workers refused, the police resorted to a vicious lathi charge. ‘We will never return to AP again. Hundreds of workers are walking on the roads for more than a month and the officials did not even offer us a packet of biscuits. Instead of helping the poor, the police are beating us mercilessly,’ a woman labourer said.41

Twenty-five-year-old Kundan cycled 1,100 kilometres to reach Patna from Panipat. He survived not only exhaustion and hunger but also intimidation and violence. After three days on the road, he was stopped on an expressway by the police. ‘You have money for cycles and not for food?’ they said as they beat him.42 Salman Ravi, a journalist with BBC Hindi found a group of labourers in Delhi who had been beaten by the police when they stopped by a road to eat the food they were carrying. They had been walking and cycling from Ambala for six days already, returning to their villages in Madhya Pradesh. One man with two little children and the family’s bedding on an old bicycle broke down as he spoke of what had been done to them.

‘What Modiji has done is good, he has been very good to us. If we’re hungry we’ll find something, we’ll manage. But at least he’s comfortable where he is…Arrey, shouldn’t he think of people who are poor? They are in distress, shouldn’t he do something? But never mind about us, we’ll go away, we’ll die, we’ll take our children and we’ll leave somehow…We’re in great difficulty, sir, we’re helpless, look at our kids.…[The police] chased us away from that border, now they’ll drive us away from here. So where do we go now? We’re coming from Ambala, it’s been six days…We bought someone’s broken-down cycle for 500 rupees, this is how we’ve been travelling…But everything is all right, all is well—those people, they’re fine where they are, they’re getting food to eat, aren’t they? They make a phone call and get what they want. Who cares about us?…We come here and the police thrash us with sticks. They beat a man there so badly he collapsed on the road. Is this how things should be?’43

Utterly broken by the suffering and indignity, a particularly anguished migrant labourer from Jharkhand working in Mumbai said. ‘Modi ki nazron mein hum keede hi hain na, waisi hi maut marenge.’ (We are mere insects in Modi’s eyes, so that is how we’ll die.) 44

[…]

In stark contrast, 300 special buses were sent by the UP government to bring back students stranded in Rajasthan’s Kota town, a hub of coaching centres for competitive exams to engineering and medical colleges that middle-class students aspire to. The air-conditioned buses were stocked with food, mineral water bottles, sanitizers and masks.47 Other states like Maharashtra, Uttarakhand, Assam, Chhattisgarh and Punjab followed the UP example. For Indians stranded abroad because of lockdowns in those countries, the Government of India initiated its much-vaunted ‘Vande Bharat Mission’. Under this emotive ‘nationalist’ banner, the union government deployed its national carrier, Air India, to bring expatriate Indians home at pre-fixed fares. Eventually, almost ten lakh Indians returned home through this programme.

The Indian state seemed not in the least ashamed or embarrassed about this open display of class bias in its treatment of impoverished internal migrants on the one hand, and middle-class students and Indians working abroad, on the other. This class bias became the hallmark of every policy choice of the union government in its response to the COVID-19 pandemic.