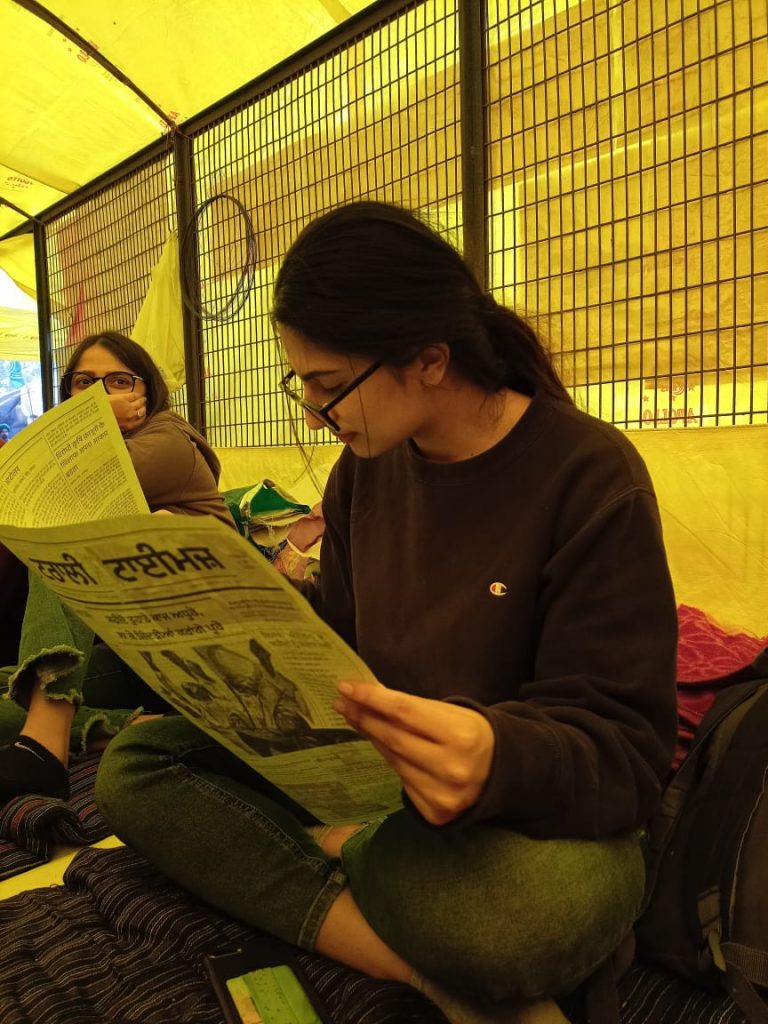

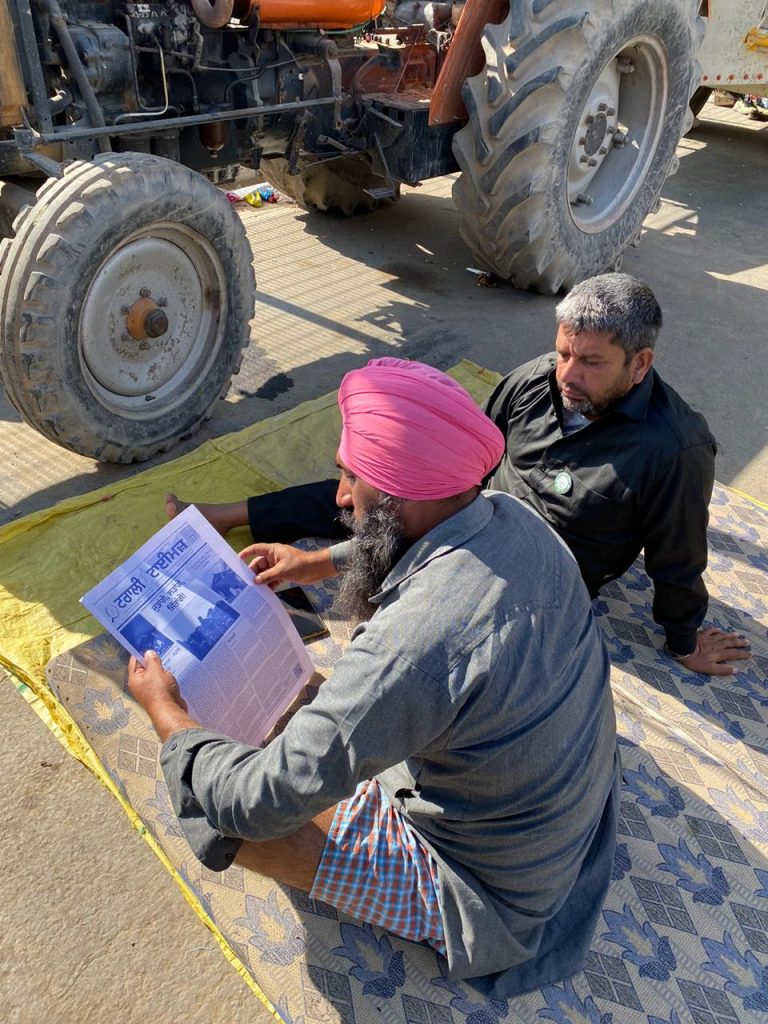

With the second edition of Trolley Times already out in print, it has established itself as an effective tool to achieve self reliance in documenting stories and voices from the protest sites of the farmers’ agitation across New Delhi’s borders. The masthead of the second edition has included increased Hindi representation and the purpose is to defy the false narrative propagated by biased media of terming the movement as solely of Punjabi farmers.

“This is an united movement of farmers of India. Different protest sites at five borders of Delhi are not isolated in any way”, explained one of the members of Trolley Times.

This is a people’s movement and Trolley Times assumes that same spirit. From crowdfunding campaigns for inviting funds, content, distribution, editing, all the tasks are completed through active volunteer participation from the people at the borders and across India.

The choice of language has been restricted to Gurmukhi and Hindi, since these languages are spoken by most of the people participating in the resistance. Special care has been taken to regularly check the content uploaded by people on social media portals to avoid misinterpretation and false narratives. The style of the newsletter assumes a vernacular and simple spirit. “The farmers speak in a simple language and the format of the newsletter conveys the same. Our aim was to create literature that is easy to access for everyone. Hard copies were circulated for in-house consumption at Singhu and other sites, and soft digitally. After the first edition we got special requests from NRIs to also translate it in English which has been made possible by volunteers and can be accessed online,” Surmeet Maavi said.

People involved in Trolley Times are youngsters filled with concrete vision and those who were actively involved in social movements and welfare activities back in their native places. They hadn’t not come together just for Trolley Times initially, but for social welfare projects such as imparting education to socially disadvantaged communities, setting up libraries, and the like.

Gurdeep Dhaliwal from the Singhu Border said, “The main stage is very far from several locations on the protest site and we felt a need for in group communication among different groups to further strengthen the movement. It was important to connect different borders and consistently inform people participating in the protest about the developments of the movement, future vision by leaders and stories within the protest. For such a vast movement, being on the same page is crucial.”

With a background in English Literature and creative writing, Gurdeep has been documenting visuals from the protest on his Instagram handle. He adds, “Trolley Times is not a mouthpiece for the entire farmer’s movement but it is our way of supporting the spirit of farmers. Clearly we were not satisfied with the reportage done by mainstream media and this is our way of claiming our narrative.”

This movement is also different in terms of the archival history it is creating. Usually during movements, students assume the frontline. We saw graffiti and installations at various protest sites creating memories and inspiration. In the wake of the pandemic, students’ participation is not as much as it was in the movements that took shape pre-coronavirus, mainly due to restrictions on commute. Trolley Times, however, is creating an alternate archival history by documenting photos, videos, songs, illustrations and stories straight from the heartland of the protest site.

An open online archive (https://kisanekta.in/) has also been created to allow participation from across the country. People have been uploading videos, illustrations, poems, songs, graphic artwork in support of the movement, giving it an inclusive character. At the end of every day, the content is filtered, as since it’s an automatic archive, it’s not possible to check all the submissions immediately.

Narinder Bhinder, on whose trolley the idea took birth, has been involved in the protests since the beginning. Earlier in December, his video went viral where he climbed onto a police car to turn off the water canon which was being blasted at the farmers. Talking about the incident, he remembers, “At the Punjab-Haryana border, we were stopped by the police and were denied movement into Delhi. At that time, elders with us advised us to comply with police and return to the villages but the youth had already decided that we have to reach Delhi to register our voices. We continued to rely on dialogue but the police attacked us with water cannons when we didn’t budge. Then I decided to climb onto the water cannon and stop it.”

Even after reaching Delhi, he was appalled to witness the treatment meted out to farmers by the mainstream media, who termed them “Khalistanis” (terrorists). This incident made them realise the need for strong in group communication to maintain transparency and authenticity of the movement.

Bhinder adds, “We continue to talk regularly among groups stationed at different borders and remind them to not do or say anything that would weaken the character of the movement. Trolley Times is a step to take back this agency of expression. We decided to publish our stories and concerns ourselves to avoid misrepresentation of any kind.”

Surmeet Maavi comes from a family of farmers with no land of their own. Recipient of a National Award, he said, “Participation from landless farmers in the movement is especially important because we know what it is to lose our lands to debts.” With a background in Mass Communication, Trolley Times was just a natural instinct. During the discussions, when everyone would brainstorm on ways to contribute to the movement, Surmeet suggested the idea of Trolley Times. Joined by Navkiran Natt, Ajay Paul, Gurdeep, Narinder and other contributors, it quickly assumed shape.

Exploring the hope and vision of Trolley Times, Surmeet said, “We did not expect an overwhelming response to our idea that was born during one of the many discussions on trollies that helped us reach here. Farmers have attached their hope with this newsletter that has also increased our responsibility to make sure we stay true to the movement by upholding its democratic and non violent spirit.”

With effective communication strategies such as vibrant Instagram pages, YouTube channels and a specialised IT cell of their own, the farmer’s resistance has garnered active support both on social media and on site.