In June this year, the J & K administration announced their latest measure to curtail press freedom and free flow of information in the region — the new Media Policy 2020. Apparently to curb “fake news and misinformation”, the policy gives governments supreme control over any news published in the region and to take criminal action against any media person or outlet that publishes something which the state defines as “untrue” or “fake”. The policy also states that the J & K Department of Information and Public Relations can withdraw and suspend advertisements to the media houses that do not meet “state standards”.

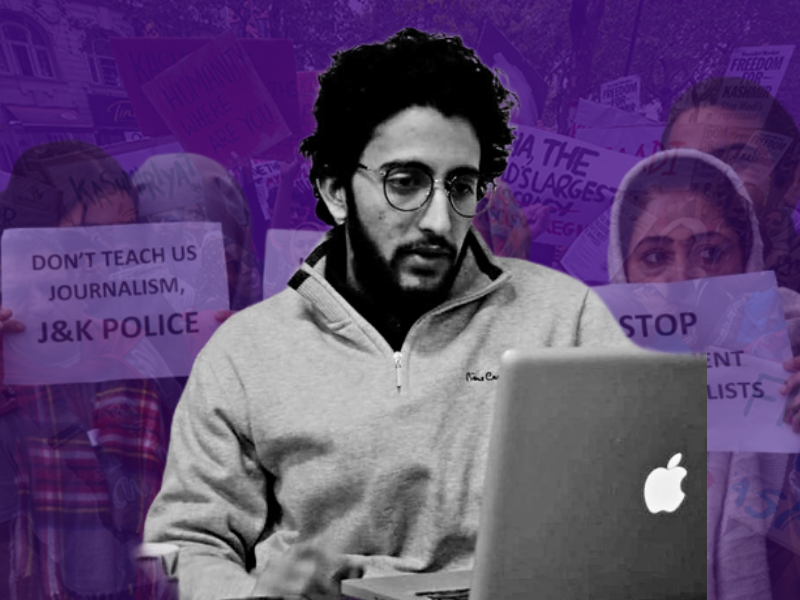

A rare & seasoned group that has worked under continued state repression for years now, J & K’s journalists don’t consider this as something new, but simply an extension of the constraints that had already existed there. Founder and Chief Editor of the online news platform, The Kashmir Walla, Fahad Shah has faced continued state abuse in the form of police summons, detentions and other attacks. In 2017, Shah was arbitrarily picked up the J & K police who questioned him for hours together about his work. In 2018, a teargas shell was fired into his room, when he was at his office. On May 20 this year, he was questioned by the police again for a report that had “defamed” them. More recently on October 3, Shah and his colleague were detained on their way back from work and questioned for several hours without any explanation.

Its amid all of this that Shah has been nominated for this year’s Reporters Without Borders (RSF) Press Freedom Award — a recognition for the “important part” his news platform plays “in defending press freedom”. Despite all the attacks, Shah (@pzfahad), who considers these state’s attempts to instil fear, has not budged. Read him discuss this and more in this interview with Mukulika R.

Mukulika R (MR): Journalists in Kashmir have lived under state repression and militancy for years now. What is different about the new media policy that’s making many of you protest it?

Fahad Shah (FS): I agree. Journalists in Kashmir have been working in very difficult conditions, and especially post-August 2019, journalism has turned out to be much more difficult as a profession. In the following months, the government introduced the new Media Policy, which, The Kashmir Walla, as an institution, is deeply critical of. However, unfortunately, many other journalism organisations or individuals in Kashmir have not expressed much dissent against this draconian policy. On the behalf of The Kashmir Walla, I had even written to the Kashmir Press Club, laying down the impact of this policy and why they should raise their voices against it. But it seems to me that most journalists in Kashmir have quietly accepted the policy and are therefore self-censoring.

I believe it’s a disease to self-censor your journalism. I have been getting summons and detentions simply because we have refused to follow the state’s censorship tactics or even agree to change our work. I don’t think there is any rule book given by the government to media houses that they should stop reporting, but despite that, some major incidents have not found space in many newspapers here. It is very unfortunate.

This new media policy, in particular, is draconian, and we have called it the “bureaucratisation of journalism”. The Kashmir Walla has written against it vehemently and will certainly continue doing so. Because under this policy, even law enforcement agencies can go after a journalist, our backgrounds will be verified and can be investigated simply on the basis of the content you publish. All of this is being done to instil fear among journalists so that they stop writing critically of the government. But the job of the press is to highlight the wrongs committed by governments, public institutions or public servants. And this is why we stay independent as a press institution.

MR: How much have things gone from bad to worse now? Could you describe what a Kashmiri journalist’s daily life is like in the Valley these days, in the light of the abrogation, the aftermath of the communication blockade, and related repressions?

FS: After August 2019, as I said, things have not been the same for the media here. Precisely because the industry is suffering from the disease of self-censorship, which has practically killed journalism. Writing about the government is fine, but failing to represent people and become their voice, is simply disastrous. And this is what has happened.

Also Read | Press freedom in the line of fire: In conversation with Anuradha Bhasin

I believe my daily life as a journalist is quite different from many others’. I have received summons, been detained from the streets, and interrogated for hours together. I continue to receive threats — both directly and indirectly. I’m asked to remove some stories at times if they are against a particular institution. When I meet people and they tell me, “why do you roam around freely?”, as they fear for my safety. All of this has only led to extreme psychological trauma in me, which I deal with on a daily basis. There is no peace of mind, although it has always been like that here. For many others too in our fraternity, it is the same. But what did we do? We have only reported about what is happening in Kashmir and not invented stories. All these are facts that perhaps many of it “should not” come out.

MR: J & K is considered by many as a laboratory for state repression, surveillance and abuse of power — acts likely to be repeated elsewhere in the country. Yet, solidarity from the mainstream Indian media has not been up to expectations. What do you account this for? How crucial do you consider media solidarity to be? How has the international media community’s response to the new policy been so far?

FS: Media solidarity is very, very important, but you are right. We haven’t seen many Indian media houses, except a few publications or editors, extending solidarity with us. For me personally, support has mainly come from a few friends in Delhi or Mumbai, and mostly abroad. Several editors and journalists based in Europe or the US continue to stay in touch and take frequent updates on how we are doing. They are eager to help us in whatever way they can.

It is important for independent media houses to come together and build an ecosystem that will help us sustain across the globe and not just in Kashmir. I don’t believe that only the media in Kashmir is facing these issues. We have many other examples too — look at Egypt or Hong Kong; see what independent media is going through in these regions. It is hard to function when the authorities are not willing to provide a free atmosphere for you to work in. The India media should be more understanding about our circumstances here, but in the end, most of them are only concerned about where the revenue comes from. They are addressing their own audience which wants to hear how a Kashmiri is brutalised.

At the same time, individuals from many states of India, as well as some non-governmental institutions have certainly come forward to help. They do try to engage with us and even find solutions and ways about how we can do better and sustain. I hope this continues and we are able to have a stronger independent media ecosystem for us here.

MR: Could you tell us about the founding of The Kashmir Walla? How did the magazine manage during the communication blockade?

FS: I launched The Kashmir Walla website in 2011 — a year after more than 100 civilians were killed in street protests by government forces. The idea of this magazine has always been to tell the story of Kashmir to the world, by the people of Kashmir themselves. As a journalist, I had experienced how many editors in India filter reports, and ideas from Kashmir to fit their own narratives. Therefore, we wanted to encourage regional journalism and not parachute work in a conflict-ridden zone.

However, all of that hit rock-bottom on 5 August 2019, when the government snapped all lines of communication and enforced the strictest of curfews the region had seen in recent history. From traffic in lakhs, we dropped to almost nil. With the private market nearing death, we were financially dependent on the traffic on the website — and without internet access, we could neither publish nor earn anything. It also paralysed our new project — the weekly newspaper in print. Due to the security lockdown and communication blackout, we were not able to reach the printing press.

Nevertheless, we kept reporting amid the crackdown. A couple of our team members flew outside Kashmir on a weekly basis in order to access the internet and publish stories on our website from New Delhi. Due to financial problems, we even shifted to a low-end print newspaper — but, more importantly, we kept rolling, reporting and analysing all the key issues for the people in the region during the most crucial of times which changed Kashmir forever.

MR: You and your colleague were recently detained and harassed by the J & K police for your reportage in The Kashmir Walla. Before that in 2017 and 2018, you faced similar experiences, besides the frequent police summons that continue. What pushes journalists like you to gather courage and go out for work again – despite the routine physical and mental pressures that the state makes you go through?

FS: For me, it is the promise I made to myself that I will tell the story of my people no matter what that has given me the courage to continue. It is about faith and certainly, to be on the right side of history. And I strongly believe that this is the right side. We can’t fool ourselves everyday saying there’s nothing to report.

Most of the major story breaks we did this year were based on incidents. And interestingly, we received multiple tips from people in those affected areas. People have faith in us — they know whom to go to when they face injustice, and I hope we have not let them down so far. We won’t in the future either. It is public service journalism that I want to be run by our own community. That is also why we have a membership model — where people, our readers, can pay us so that we are able to continue this work. We want The Kashmir Walla to be fuelled by people and not by the powerful entities of the society, who have their own interests in shaping media-scapes.