10th December is the UN observed Human Rights Day, marking the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Adopted in 1948 by the United Nations General Assembly “as a common standard of achievements for all peoples and all nations. It sets out, for the first time, fundamental human rights to be universally protected”. Emerging from the experience of the second world war, this declaration is the foundation of international human rights law and covers rights and liberties including freedom from any form of discrimination, torture, slavery; equal access to law, and more.

Over the decades, the UN and its affiliate institutions have been criticised for their inability to take concrete actions, especially when ‘first world’ powers are in the dock. And yet, it is the framework of international human rights which provides means to address the structural implications of colonialism, old and new, as well as systemic discrimination. In the context of the many struggles of independence in the global south, in 1960, the UN adopted the landmark declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, which “affirmed the right of all people to self-determination and proclaimed that colonialism should be brought to a speedy and unconditional end”.

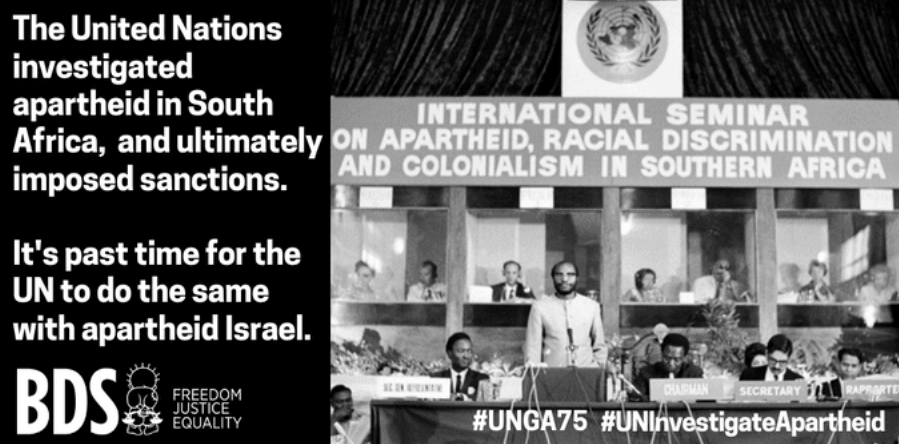

Indeed, the UN mechanisms translated into concrete action when it imposed an arms embargo on apartheid South Africa in 1977, following an investigation which found the regime guilty of the crime. Decades of grassroots struggle followed by these sanctions not only ended apartheid in South Africa, they also gave the world the classification of the specific crime of apartheid, eventually classified as a crime againt humanity.

The question of Palestine has been a permanent feature in the United Nations. In 1975, it adopted a resolution, which was later revoked, that declared Zionism as racism. Over the years, Israel’s massacres of Palestinians, as well as illegal settlements, annexation and other violations have been brought up in the various platforms even though concrete action has not followed. In February 2020, the Office of the Commissioner of Human Rights brought out a list of 112 companies that are involved in Israel’s illegal settlement enterprise, based on a detailed criteria. Not only is this list to be annually updated, it is a first such concrete step towards accountability from corporations profiting from Israel’s occupation and colonialism.

This list came after years of grassroots work by human rights and civil society organizations to demand accountability. Just as the arms embargo on apartheid South Africa came after years of work by South Africans. This included campaigns for boycotts which global solidarity groups diligently took up. With respect to Palestine, the violations of international law and human rights by Israel are well documented for decades. It remains the litmus test of the validity of the very framework of international human rights law.

In May this year, Israel announced its plans for formal annexation of parts of occupied Palestinian territories. Since then, the understanding of Israel as an apartheid state has grown, and so has the demand of the UN to investigate Israel for this crime against humanity, as it did in the case of South Africa. From civil society organizations to elected MPs and diplomats, this demand has found increasing resonance. It is evident that UN mechanisms can be mobilized in the right direction when there are movements on the ground that cannot be ignored any longer. And therefore, the demand for the UN to investigate Israel for apartheid against Palestinians must be sharpened, especially in the global south where struggles against colonialism connect us intricately with Palestine.