Through a series of fascinating essays—delving into geography, history, myth, sociology, film, literature and personal experience—Shylashri Shankar’s Turmeric Nation a Passage Through India’s Tastes traces the myriad patterns that have formed Indian food cultures, taste preferences and cooking traditions.

From Dalit “haldiya dal” to the last meal of the Buddha; from aphrodisiacs listed in the Kama Sutra to sacred foods offered to gods and prophets; from the use of food as a means of state control in contemporary India to the role of lemonade in stoking rebellion in 19th-century Bengal; from the connection between death and feasting and between fasting and pleasure, this book offers a layered and revealing portrait of India, as a society and a nation, through its enduring relationship with food.

The following is an excerpt from the chapter “Food and the Nation” of the book.

When something functions as such a powerful marker of a group’s identity, it is not surprising that social and religious movements and political parties have cottoned on to food, and particularly the beef issue, as a way to create a band of the committed, a vote bank. Veg versus non-veg became a cultural question for Indian nationalists…

Vivekananda focused on energising the Hindus in India, and this is evident in his response to the question of whether meat eating would include beef. No, said Vivekananda. All Hindus were united on one thing—that they did not eat beef. Why? Because the cow is a sacred animal, and here his discourse links being a Hindu with religion, and with inhabiting the land of India. Cows and buffaloes were slaughtered for meat in abattoirs run by Muslims, so this group became the immediate target of rioters led by the gau-rakshaks in the late nineteenth century.

The present-day gau rakshaks hark back to the late nineteenth century when a Hindu revival movement, the Arya Samaj, was launched in UP and Punjab and other parts of North India by Swami Dayanand Saraswati, who also called for saving the cow from slaughter. The Gaurakshini Sabha (Cow Protection Society) in 1882 was one of the most potent markers of the Hindu revivalist movements in the nineteenth century and provoked a series of communal riots in Punjab between Hindus and Muslims in the 1880s and 1890s. Bal Gangadhar Tilak took it up in the Deccan by creating Cow Protection Societies in prominent cities in India including Nagpur, Pune, Hyderabad, Madras. Lodged within these associations (where public talks were on rights, freedom and equality), were secret revolutionary cells that plotted violence against British officials and personalities.

It is no accident that the cow was chosen by these organisations to connect with Hindu Indians. What better way than to use the cow, which the Hindu religion reveres, as a rallier of Hindus? Neither is it an accident that the meat in question is only beef, which marks the line between those who consume it, and those who only eat other meats, poultry and fish.

What is interesting for our purposes is that the nationalists could not affix a boundary around vegetarianism and connect it to an Indian. This is because Hinduism offers multiple ways to achieve liberation, moksha. There is a ritual way to moksha, which demands utmost concern with purity and hence confines itself to vegetarian fare, and a bhakti way, which does not require such ritual purity. Non-vegetarians too can attain liberation. In this sense, Hindu culture is more a fluid entity in which the strictest rules and highest values are only prototypical but not essential.

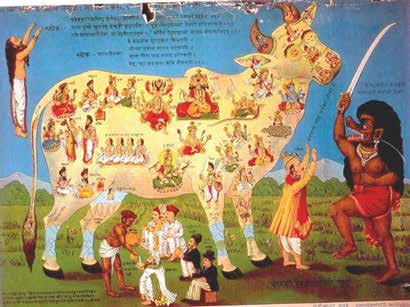

Agorakshanasabh (‘Cow Protection Leagues’) and ‘wandering ascetics’ used this pamphlet to protest against cattle slaughter.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Katherine Ulrich’s work on the Buddhist, Jain and Hindu modes of dealing with food, and their food fights with each other, offers us an interesting way of approaching the ambiguity surrounding meat in Hinduism. The three religions rank non-violence differently in the creation of their cuisines. Buddhist rules are driven by a fairly equal emphasis on the importance of almsgiving (especially for the laity), non-attachment (especially for the renouncer/monk), the practice of austerities and the need to avoid violence.

Jainism shares similarities with Buddhism—both reject the Vedas and emphasise renunciation as a prerequisite for spiritual advancement. But Jains have a different criteria for food rules: non-violence is central, while austerities and almsgiving are important. This is because for Jains, karma is a physical substance that could be ‘dusted off’ from the soul by physical acts of catechism, particularly but not exclusively by fasting. For Buddhists, on the other hand, the metaphysical nature of karma makes mental/volitional acts of greater importance than the physical ones of fasting or vegetarianism.

In contrast, for Saivite Hindus, vegetarianism and non-vegetarianism are secondary to devotion to god. A bedtime story I remember listening to as a child was about Kannapan, a hunter who makes an offering of water (carried in his mouth) to a Siva lingam. A Brahmin priest scolds him, at which point the eye on the lingam begins bleeding. Kannapan cuts out his own eye and places it on the lingam. The second eye on the lingam begins bleeding. Kannappan then decides to pluck out and offer his remaining eye as well. Before he does this, he puts his big toe on the lingam so that he would know, even when he is completely blind, where exactly he should place his second eye. The Brahmin is outraged by this further desecration, but Lord Siva appears in front of Kannapan and blesses him, restoring his sight. The Brahmin priest realises that purity and pollution pale in front of devotion. It is not surprising that a majority of Hindus and Buddhists are non-vegetarian, while Jains are vegetarian.

These food fights are evident in Tamil literature from the tenth century. The main group attacked in the verses of Nilakeci, one of five minor epics of tenth-century Tamil literature written by a Jain, are the Buddhists who are criticised for permitting their adherents to eat meat as long as they do not personally slaughter it. The poem also chastises Vedic sacrifice on two grounds: that sacrificial killing results in negative karma, and deities do not need such bloody offerings. Brahmins are associated with Vedic sacrifices, and hence with non-vegetarianism rather than vegetarianism. Even today bali (sacrifice) is offered by Brahmin priests too, in the form of vegetarian symbols such as pumpkin or lime. What this tells us is how fluid caste identities are in inhabiting categories such as pure and polluted, veg and non-veg, clean and unclean.