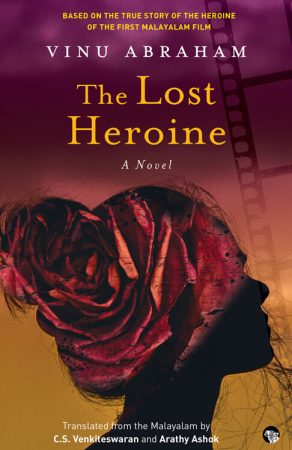

Vinu Abraham’s novel Nashtanaika (2008) recreates the life and times of PK Rosy, heroine of the first feature film made in Kerala, Vigathakumaran (The Lost Child), in 1928. A dalit from Trivandrum, Rosy was for many decades written out of mainstream accounts of the early history of Malayalam cinema. As Abraham notes in the Introduction, the known facts of her life would barely run to three pages and we have no photographs of her. But, as a dalit, a woman, and a Christian, Rosy was a pioneering figure of Malayali popular culture. We owe her recognition, along with the circumstances in which she lived and worked, if we wish to preserve a true memory of the origins of Malayalam cinema. Abraham’s novel, a runaway success in Malayalam, was adapted into a play and also a highly successful film; it now appears in English in CS Venkiteswaran and Arathy Ashok’s translation as The Lost Heroine.

The following is an excerpt from the book.

The Kakkarissi play opened before Rosy a new world of experience that she had not known before—an experience called art. She was very much enamoured by the role of Parvathi. Parvathi was a beauty, and Rosy was enthralled by her dance steps, her songs and dialogues.

But later, she was surprised when she heard what Neeli Akkan said. Neither Parvathi nor Ganga nor the Queen nor the rest of the actresses were women. They were all men in disguise. Can the men transform themselves to become such beautiful women? No woman had ever done a role in Kakkarissi plays before, Neeli Akkan added.

The Parvathi whom Rosy saw in the Kakkarissi play refused to leave her mind. Often when Rosy was sure that there was no one around, she would pretend to be Parvathi or Kakkalathi or Vettuvathi and sing and dance like them. Near her hut, there was a lonely bush on the side of the pond. This was where she did her acting.

‘Thatha, thikathi thakatha, they they, thatha…’ She danced while singing the song that rose on the stage when Parvathi first appears in a Kakkarissi performance. Then pretending to be Kakkalathi who reads the King’s palm, she thundered out the fiery speeches that Kakkalathi made against the forces of the dark and the demons. Holding a small piece of mirror near her face to see her changing expressions, she enjoyed the emotions and dialogues all by herself.

One evening she was in full flow, enacting the role of Parvathi by the lakeside. She had just taken a breath after delivering a passionate speech when she heard a clap and a firm voice congratulating her, saying, ‘Koche, that was brilliant!’

Rosy was amazed. She turned her head in the direction of the sound. At first, she could not see anyone. The next moment a man came into view from behind a huge jackfruit tree. He must have been more than sixty, but with a firm body and bright eyes. He was dressed in a white mundu with a towel folded across his shoulders.

Rosy felt that she had seen the man somewhere before. That too very recently. Nor was this an ordinary meeting. That was definite. By then he had reached very near her.

‘Girl, who taught you how to perform in Kakkarissi plays?’

Hearing his question, Rosy turned pale. Didn’t Neeli Akkan say that girls should not play or are not allowed to play Kakkarissi? Did I break that custom? What if the news gets around that a Christian—that too a Dalit—has broken the custom of Hindus? She trembled at the thought.

‘Ayyo, I was simply mimicking it…I haven’t studied anything,’ she stammered.

‘Hey penne, why be afraid? What you played just now was Kakkarissi. It was well played too. Ha, my name is Govindan. I’m a Kakkarissi Asan.’

Next, Asan acted out the humiliation and distress that had played on Rosy’s face in that moment. He laughed out loudly. Watching his acting, his pupils who had also arrived at the spot by then joined in the laughter. His humour was so infectious that it was not possible to take offence. Rosy protested mildly, ‘Enough of this, Asan! Don’t make such fun of poor people like me.