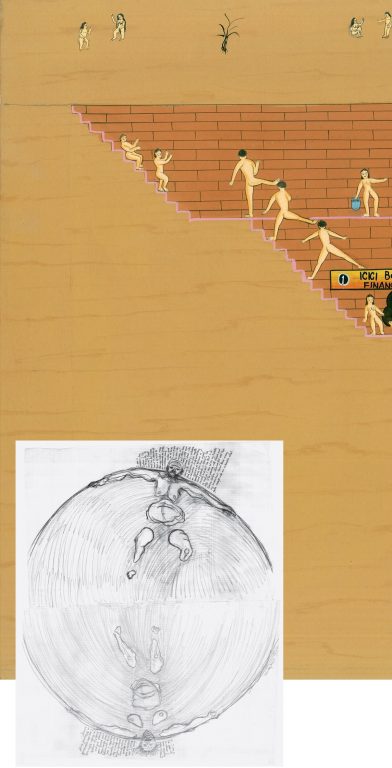

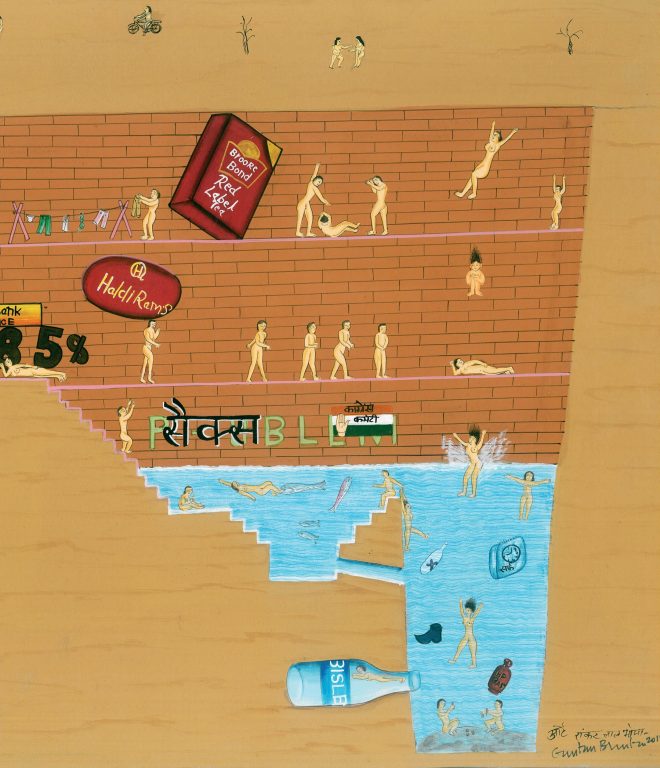

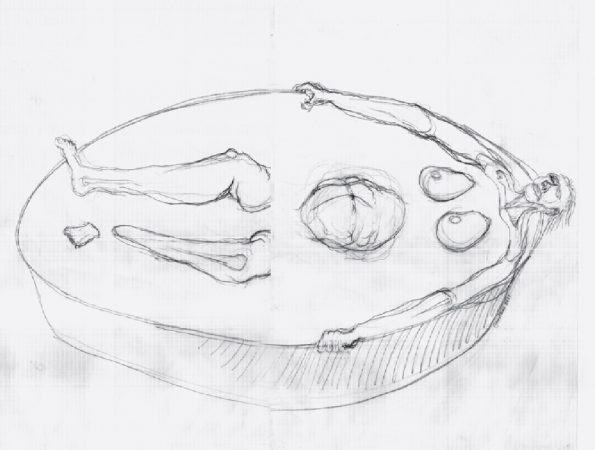

Architect and artist Gautam Bhatia’s Delirious City: Polity and Vanity in Urban India is as much a collision of various mediums as it is of mixed messages, concocted out of a desperate urge to make sense of the City, its residents, their aspirations, and their perennial expectations.

Daily life, events, places, and personalities—houses, builders, parks, malls, bureaucrats, politicians, the rich, the poor, the labourer and the liquor baron—all are condensed as a virulent strain of muddled voices that describe our civic reality. Bitter tragedy, urban despair, and personal desire emerge in daily urban encounters and manifest a euphoric edge, often yielding to subversive comedy.

The following is an excerpt from the chapter “Us and Them” of the book.

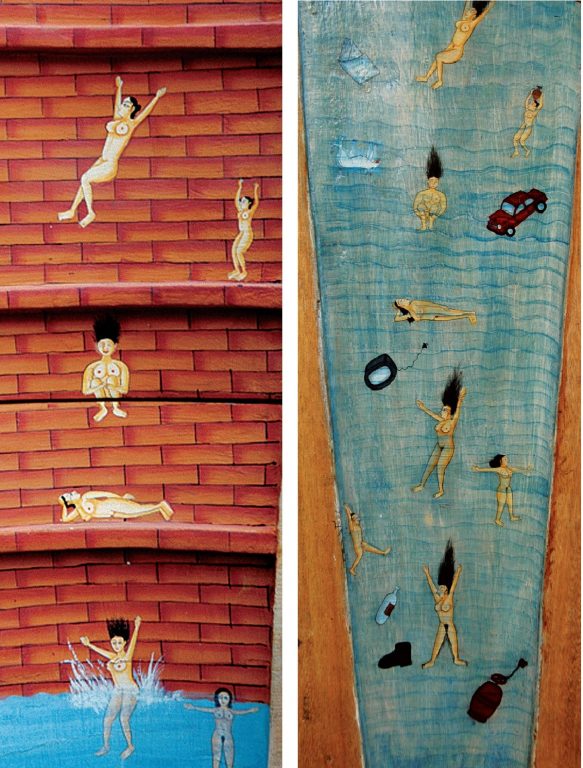

Beyond gravelled pathways, behind high walls, protected by dogs and personnel are allusions to luxury so eccentric and exaggerated, it is hard to believe that the same high walls are shared by some of the city’s poorest. Propping their broken plastic tenements against it for support, people line up to scrub themselves, one by one, under a handpump. Whilst inside, a swimming pool is drained to provide fresh blue water in case there is a sudden urge for a dip. Delhi’s mean streets are stalked by two disparate groups—an agrarian underclass that moves between sewer pipes and the low huddle of slums and flyovers, and an instant aristocracy that rides in BMWs and Jaguars between malls and tennis clubs, perpetually stuck in traffic between cows and camel carts. The rush to eradicate one’s history thrives in both breasts. The city’s oldest enemies desperately need each other, but assiduously protect their turf with prayer and shotgun, baksheesh and backbiting. Meantime, Chrysanthemum shows, rapes, poolside parties, and the murders of elderly couples form the lifeblood of its civic vitality—the essential song and dance of a place where the survival of self is primary.

The city thrives on a slippery dilemma; a daily battle of wits between the rich and the poor.1 On one side is an existence based on the instantaneous absorption of all the excesses of the American way of life. On the other, a seemingly endless struggle just to stay alive. Compare, for instance, the lifestyles of the rich and the poor residing on adjacent city plots. A Delhi farmhouse with four bedrooms, a pool, and extensive garden acreage has an average density of two families per hectare; the neighbouring slum accommodates 400 within the same space. The farmhouse also consumes 800 times the water, electricity, and energy requirements of a slum family. In land, utilities, and services, will there ever be a common ground of agreement?2 If the divide in the cities becomes less apparent, and the poverty less degrading, there may emerge a truer expression of ordinary city life.

But the culture of division will never let that happen. Within the strict bounds of the undivided Hindu family, the city remains a civic devise without structure. Its mean streets are stalked by ordinary men with extraordinary ambition—some plain traders in goods and services,3 others pitiless and demanding in their purpose.4 Where murder, rape, and bribery are predictable fallouts of ordinary transactions, life can become a messy, gut-wrenching, tiresome, demanding, enriching, as also contaminating experience. Everywhere you look, there is a performance taking place: people cooking, sleeping on the sidewalk, hanging laundry, groping on a park bench, someone being molested, someone being run-over, a man receiving a bribe. Everything that makes the city a vital, thriving, completely spontaneous act is happening before your eyes. Merely stepping outside the gates of your house makes you feel as though you have been sucked into the monsoon current of the Ganga. Observe all you like, make theoretical or demographic assumptions about the city, draw five-year master plans, collate statistics about housing, uplift slums, but to no avail. The physical side of the city swallows you up completely. Against the torrent of the newfound affluence of some, the unrealised expectations of others, and the deadening self-propagation of all, the city becomes an impossible ally, a hostile escape route. Day in and day out, you are reminded of a place built on the foundations of easy money and violence. A BMW mows down sleeping labourers; a school student shoots his teacher; another kills his daughter for spare parts.5 You walk out with your eyes firmly on the ground, watchful and wary, knowing full well that, barely ten steps into your trip, you will be consumed like a plate of food before a starving child. If you have lived in the city long enough, you know how high to build the boundary wall, when not to open the car door, when to run the red light, when indeed to hit and run.

Is there even a desire to make the city hospitable to all its citizens? Or to ensure that there are no glaring gaps in the people’s standards of living?6 I think not. Instead, the visibility of this inequality makes people do strange things.

1. House Exchange: Servant in large south Delhi house wishes to exchange the servant’s quarter for a quiet bungalow in the hills or by the seaside. Fully furnished quarter with wall-to-wall flooring, ventilator overlooking driveway, and shared bathroom with cook’s family. Comes fully furnished including an antique charpoy and raw wood table. Chair optional. Has to be seen to be believed. Servant going on sabbatical for 6 months.

2. Subsidy of 50 per cent on electric power now available to well-to-do farmers in Punjab with extensive land holdings. Additional seed and fertiliser subsidies also available. Only prosperous farmers may apply to: Government of Punjab, Chandigarh.

3. Saturn Healthcare, the largest surgical organs buyer in Asia, is looking for suitable donors. We offer the best rates for various organs: Lungs—Rs 200 per lung; Kidneys—Rs 800 per kidney; Heart—Rs 9,500 per heart; Stomach lining—Rs 300 per running foot; Feet—Rs 2,650 per foot; Tongue (dry)—Rs 300 per tongue; Tongue (with saliva)—Rs 350 per tongue. Note: Donors must be healthy and carry a fitness certificate. Donors from wealthy families preferred. Saturn Group of Companies, 13/162 B, Basement, Ansari Lane, Saharanpur.

4. Appeal: I, Kalidas Sharma, make a sincere appeal to all kindhearted citizens to help me in my hour of distress. My wife Rita Sharma is awaiting emergency liposuction and nose reconstruction surgeries at the Kailash Cosmetic Centre. She is already under heavy anaesthesia. Please donate generously. Cheques or cash may be sent to: Kalidas Sharma, 13/B6 Mongol Nagar, Kanpur-6. Donations above Rs 10,000 will be acknowledged in Mongol Nagar Weekly. GOD BLESS!

5. Rajasthani couple newly arrived in the capital for employment, presently working as labourers on the Janakpuri sewage line, wish to urgently sell their nine-yearold daughter’s organs for cash. Girl in pink of health. Interested parties may contact Dharam Lal contractor on site.

6. SHANTI-TOWNE: For once in your lifetime, dream of a home in Shanti- Towne. Features: 4 acres in the heart of Indore; 800 single-room dwellings designed along traditional lines. Shared handpump on road with weekly tanker supply. No drainage, no sewer lines means no maintenance problems. Ideally located in affluent area for easy employment. Limitless electric power available from nearby cables. No escalation in sale price till colony is regularised by local MP. Sample flat ready.