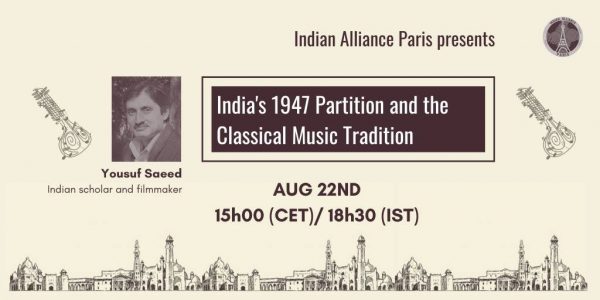

On August 22, documentary filmmaker and cultural activist Yousuf Saeed, delivered an online lecture on the impact of the 1947 Partition on Indian classical music and its various related strands. The discussion was organised on Facebook by Indian Alliance Paris, “a collective of students, researchers, & professionals in Paris interested in the socio-political landscape of India”.

While a lot of academic research has gone both into the Partition as well as the condition of classical music before this, rarely has academia paid attention to areas where both these come together, according to Saeed, who travelled all the way to Pakistan many years ago to find out the many missing links. Subsequently, he directed his 2005 documentary Khayaal Darpan based on the same subject.

Classical music in India, both Hindustani and Karnatic, had received ample patronage from the royalty and nobles, pushing it into the hands of the elites where it still largely stays in contemporary India. The Mughals were one of the greatest patrons of Hindustani music in Delhi. However, with their decline by the mid-19th century, most artists dependent on the royal court for sustenance, had to travel to far off places under local kings like Lucknow, Gwalior, Rampur, Hyderabad and the like. The many great Hindustani musicians we hear of now started off in Delhi but were pushed out of it mainly due to the financial strain that came about with the fall of the Mughals, said Saeed.

The filmmaker touched upon the revival of Hindustani classical music that took place before Independence and Partition in India. The restructuring of Indian classical performing arts that took place as part of the national movement is well known now. Historian Janaki Bakhle, in her work Two Men and Music: Nationalism and the Making of an Indian Classical Tradition, talks about Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande and Vishnu Digambar Paluskar, who did two things as part of the revival: one, they documented the most famous compositions of the time that till then had remained oral tradition alone; secondly, they shifted the focus of the music from sringara (romantic/erotic) to bhakti (devotional), in order to take it out of the stigma that was attached to it by elites. Members of the upper castes-classes were against their children learning classical music at the time, since they considered it a “lowly art” due to its association with North Indian courtesan culture. Bhatkhande and Paluskar, both based in Maharashtra, were at the forefront of reviving this art and reinventing it to suit the tastes of those who looked down upon it.

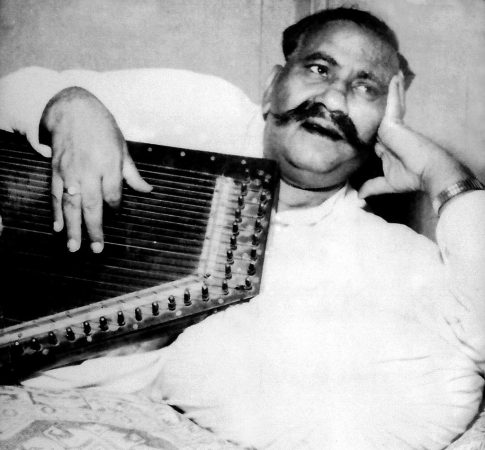

The different “gharanas” came to signify the places in which classical musicians settled down across northern India, following which they established their musical style there and passed it on to younger generations. There still are marked differences between these local traditions even though there have been multiple exchanges. Many of these traditions were affected by the sudden disruption caused by the partitioning of land, whereby many musicians had to travel across newly built borders. Gharanas in Agra, Gwalior, Delhi, Jaipur-Atrauli, Kirana, Shamchaurasi, and Qawwal Bachchon Gharana are a few which were affected and musicians like Amanat Ali and Bade Fateh Ali Khan (Patiala), Salamat and Nazakat Ali (Shamchaurasi), Rosharana Begum (Kirana Gharana), Sharif Khan Poonchwaley (Poonch, Jammu) are some who went to Pakistan post 1947.

Classical music was not the only form that was affected by the event. Punjab and Sindh still are areas with rich Sufi music traditions, along with Guru Nanak’s legacy. Nanak, who grew up in a largely Muslim milieu, had learned quite a lot from the Sufis and one of his companions was Mardana, who played the rubab. There was a whole string of Muslim rubab players in the regions that are now in Pakistan, who used to play kirtans and such along with their Sikh companions. This relationship was therefore violently broken as Sikh musicians shifted to India and the Muslims stayed back in areas that then came to be called Pakistan. What’s important in terms of classical music is that most of the Sufi traditions that existed in these regions were not only about folk/Sufi music, but consisted of “grey areas” too, where it blended with the former, said Saeed. Most of these traditions made use of the technicalities of Hindustani music, like its ragas and talas.

Such a disruption was however only temporary, according to Saeed. Quoting Ustad Amir Khan, who said that art and knowledge cant be partitioned like property, he said that music continued to travel and merge with each other despite new borders.

Saeed added that similar changes were taking place along the Bengal border as well — musicians like Panna Lal Ghosh and Alauddin Khan Sahab came from present-day Bangladesh to India after the Partition. Some like Amir Khan (1912) were born in present-day India and chose to remain here.

Post Partition, Saeed said, there was an attempt in Pakistan to “sanitise” its culture and purge it of all “Hindu” or “un-Islamic” influences, but only for a brief period. Classical music, which had an obvious “Hindu” flavour, were ordered not to be performed and if performed, were prohibited from uttering the names of Hindu gods/goddesses. This led to the formation of newer genres in the country, as for the artists to survive in such a fraught milieu, they had to experiment. Drupad and Khayal were replaced by Ghazals and Qawwalis, which emerged more popular among the new audience of a newer country. Musicians were wary of passing on their knowledge of classical music to younger generations as there was no market for it. This contributed to musical experiments in 1960’s Pakistan, which blended classical music with other genres. The era also saw the rise of Pakistani pop music. Such developments made it a more popular form of art than it is in India, where it still remains within the hold of the elites.