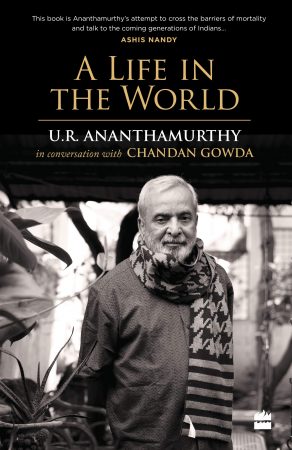

A Life in the World: UR Ananthamurthy in conversation with Chandan Gowda is an attempt to map the spirited mind of one of the greatest writers and public intellectuals of our times, through a collection of fascinating interviews done between 2012 and 2013. The book covers a wide range of subjects, including caste and religion, politics, globalisation, farmers and Dalit movements, language and literature. Besides this, the collection also contains vivid personal anecdotes from the writer’s life — his childhood, friendships, public involvements, and more.

In the excerpt below, the writer talks passionately about the Kannada language.

CG: You did not publish your thesis after getting your PHD (in 1966).

URA: My thesis got very good reviews. Upward appreciated my insights and felt I should publish it. He sent it to Isherwood who said it could be published with a few changes, because there was no such thing published on the 1930s. I could have done it, but I didn’t want to be seen as an English professor. And I did not want to spend any more time writing in English. When I write in English with great concentration, I lose some Kannada. And when I write in Kannada, I lose some English. Its very difficult to be truly bilingual, particularly when you use language at a very high level of concentration of meaning.

Before I returned to Mysore, there was a Commonwealth conference of African, Australian and Indian writers, but all of them were writers in English. Indian English writers also went — R.K. Narayan, for instance. I wrote a letter to The Times Literary Supplement saying this was not truly a Commonwealth conference. It was not against R.K. Narayan, whom I admired. I said, ‘If India is to be represented, it should be represented with its various languages. Tamil is a very ancient language. Kannada is an ancient language. Writers in these languages are not represented. If Commonwealth becomes only English, it loses its meaning.’ This letter was published. TLS wrote an editorial supporting me. All my teachers also felt that I had taken the right stand about language. I had just then read a book called The Triumph of the English Language and knew how long it took English to triumph, to become the official language of England. So, I thought Kannada would also have to struggle.

When I came back, CDN, who really was a big influence in my life, did not take me into the postgraduate department (the master’s degree in English is now being offered at Manasa Gangotri, the new campus of Mysore University, whereas the BA degree continued to be taught in Maharaja’s College, Mysore). He was my teacher. I had loved him and he had great love and affection for me. He had sent me to England. But he thought that I would become a language chauvinist. I told CDN it was unfair, but he said, ‘I dont believe that you will develop the English department because you are anti-English.’ I said, ‘I am not anti-English. I want English for comprehension for everyone, and its great literature to be studied by people who want to study it. The way English is the language of England, Kannada should be the language of Karnataka.’ And so he had no real argument against me.

Then, there was a Lohia movement which wanted Kannada to be the official language of Karnataka. For the first time as a teacher, I went in a procession. I led the procession. Our slogan was: ‘English Ilisi, Kannada Belasi!’ (Unseat English, Nourish Kannada).

CG: In Mysore?

URA: In Mysore. It came in all the papers. Each time I applied for a reader’s position at Mysore University, Professor CDN would come in the way and say, ‘No, he is anti-English.’ But later on, he changed his mind. Because he knew the quality of my writing, and he was a man of grace as well. He took me in and then I had no quarrel with him, but I had to struggle ideologically. Otherwise, I would have been ashamed of myself.

And then I came to Manasa Gangotri as a reader in English after teaching for three or four years in the Regional College of Education. I got the Homi Bhabha Fellowship for two years. This was in 1972. I wrote my second novel, Bharathipura, at this time and things were smooth afterwards. I stuck to my stand on how to keep English within our cultural complex all along. I still take that stand. It is an idea which will not die.

CG: You have not written any literary criticism in English?

URA: I have done some writing in English to justify my job. But everything original I have written is in Kannada, which sometimes was translated into English. My mind developed both in English and in Kannada, but I chose Kannada for self-expression.

CG: Did your realization about the place of Kannada in your life and in your intellectual life make you view the task of English literary criticism differently, the task of teaching English literature differently? You taught for a couple of decades in the English department.

URA: I had seen in England great teachers of German literature. Students would study German literature very deeply and write dissertations in English. I knew that the language you choose is not important. The literature is something very different. I thought of writing a PhD thesis on Shakespeare in Kannada. That’s the best way to really own English. And I was never against English for communication.

And then my teaching changed. Because when I taught modern poetry, I was making modern poetry in the Coffee House with Gopalakrishna Adiga. I could make connections with my language and English, which was a great advantage.

When I taught Mathew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy, I connected it with the Emergency in India. I have never taught a text in a blank space. I connected it with my literature, with my writing, with what is happening around me. Being a Kannada writer gave me roots; roots which helped English to grow within me. If I talk about Yeats or somebody else, I have a point of view very different from a British critic because I bring my own literature into operation.

CG: How did you encourage your students, your PhD students, to appreciate the kinds of intellectual concerns you had?

URA: Dr Ramachandra, who worked on Conrad, was intellectually close to me in matters of this kind. Nowadays, doing a PhD has become another kind of examination. You get a certain kind of fulfillment when somebody is interested in two or three literatures in a comparative way. I had it with Dr Ramachandra. He is now retired, but he is still a teacher.