August 5 marked a year since the abrogation of Article 370, following which the state of Jammu Kashmir was bifurcated into two and its special rights were taken away by the central government. The state has, ever since, been left suspended between a number of changes as well as utter stagnation, both at the same time. While there has been an expected rise in illegal detentions, destruction of property, the seizing of land by the army, the abuse of journalists and the curbing of press freedom — all contributing to the deterioration of mental health in the region — there has also been an unhealthy inactivity in terms of education, employment, economic progress and the like, as all of this has been stifled with no resources in aid. The plight of Kashmiri students with low internet connectivity amid the central government’s push for online education has been particularly worrisome.

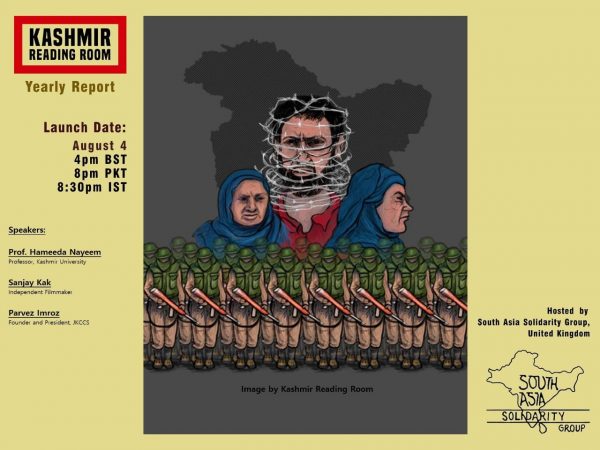

As part of commemorating a year since the abrogation, the Kashmir Reading Room (KRR), a group of lawyers, academics, activists, researchers and the like, released a report scrutinising the condition of Kashmiris and the various aspects of Kashmiri society following August 5, 2019. The report was launched and discussed at a webinar organised by KRR and the South Asia Solidarity Group-London (SASG) on August 4, 2020.

With around 4000 attendees, the webinar started off with writer-activist Amrit Wilson introducing KRR as a group set up in 2014 to inform people about the “everyday struggles of the people of Jammu & Kashmir” as well as to “foster an understanding between the people of India and Pakistan”, which they feel is necessary for conflict resolution. The other speakers were Kashmir University professor Hameeda Nayeem, independent documentary filmmaker and author Sanjay Kak, and human rights lawyer and activist Parvez Imroz.

The report, titled Dis-Integration at Gunpoint, contains several sections with interviews, studies, and articles. Divided across three parts, these sections cover crucial areas like politics, legal matters, economy, culture, media and more. It also consists of important letters, statements and other documents drafted by KRR post August 2019, as well as the letters the group sent to the United Nations regarding the human rights violations that have been taking place in J & K.

Wilson said, “we are launching this with an awareness that India’s relationship with Kashmir has entered a new phase of occupation similar to Israel’s settler colonialism. The past one year has not only seen a brutal lockdown, but also the longest ever internet and communication blockade in the history of any democracy together with serious violations of human rights”. She added, “What is even more significant for the future of the region is the BJP government’s facilitation of demographic changes, corporate plunder, and ecological destruction in the region. On another level, it is the first step in the BJP’s expansionist policy of Akhand Bharat”.

Hameeda Nayeem, professor at the Kashmir University, said that what happened on August 5, 2019, was only the last nail in the coffin, because Article 370 and the special protection offered to the state had already been hollowed out by its numerous violations by the government and the army. All that the Article had was a symbolic existence, to which Kashmiris held onto and could demand their rights with, however, that possibility too was abandoned by the abrogation. Comparing the situation of Kashmiris to being “surrounded by a huge deluge and cut off from the rest of the world”, Nayeem said that the abrogation was a “legislative murder which facilitated the sudden disenfranchisement of the entire state”. She also touched upon the psychological impact of all this on the younger generations of J & K and said that she was particularly disturbed about this. “An entire generation is being affected. They are growing up in cages, when they are to experience the open world of learning”.

“Some 8-year-olds had lost the ability to play spontaneously, and instead, would sing songs of martyrdom where they proudly proclaim that the only objective in life was to march to their death in the quest for freedom. Teenagers and the youth, initially mistrusting and reticent, would break down and pour their hearts out once they got to know us better… We met parents who appeared jaded and burdened by the looming threat, uncertainty, and inability to ensure safety for their children and families. Such repetitive and violent trauma in endemic war zones can be deeply damaging for the community, especially children and adolescents who could be scarred for life and pass on their fear and anger to generations that follow.”

(From Dis-Integration at Gunpoint, “Mental Health and Kashmir: A Longitudinal Perspective”, Dr Amit Sen)

Nayeem concluded by saying that the Opposition, particularly the Congress, has been a “disaster” in addressing the issues of Kashmiris, due to which the common youth of the country had to rise to the occasion for J & K.

Adding on to this, filmmaker Sanjay Kak said that the situation was “unacceptable and unconscionable” because there is a clampdown on simply anybody who dissents in the country, and that the greatest weapon against this would be a “clear headed understanding of things”. Kak also said that the area covered by the KRR report was especially worth mentioning, because apart from Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh, it includes regions like Gilgit-Baltistan. “Outsiders may not be able to comprehend this relationship, but there is an intricate set of connections between the people of these regions”. Another interesting feature of the report, according to Kak, was that it speaks of the less discussed aspects of J & K, for example, its minorities besides the Kashmiri Pandits — namely, the Kashmiri Sikhs and Shias — and the attacks on such groups.

“While militancy has triggered a slow migration to urban areas in the capital Srinagar and the highly urbanized Baramulla city in the north, the bulk of the Sikh population in south Kashmir still lives in rural areas in Anantnag and Pulwama districts. Several Kashmiris whom I interviewed – both Sikh and Muslim – repeadly alleged that the intention behind targeting the micro-minority Sikh community was to create a Sikh-Muslim communal divide and similarly trigger a mass displacement of Kashmiri Sikhs”.

(From Dis-Integration at Gunpoint, “Kashmiri Sikhs after Abrogation”, Khushdeep Kaur)

The last section of the report is about the media, the curbing of press freedom in J & K and the attacks on journalists in the state. Amid the lockdown and communication blockade imposed in the state following the abrogation, Kashmiri journalists had organised multiple protests.

“Besides a halt in uploading and updating the online editions, the free flow of information came to a grinding halt… Editors lost contact with their stringers or reporters. Offices were shut… The severe restrictions on movement for at least two weeks, and surveillance made it difficult for editors to even physically go in search of their reporters in rural areas… The editors had also been summoned by a federal investigation agency concerning the conflict in Kashmir… there was increased surveillance of newspapers and intimidation… The drastic decrease in revenue forced newspapers to curtail salaries”.

(From Dis-Integration at Gunpoint, “Amidst Harassment and Persecution, Resilient Journalism Continues”, Freny Manecksha)

Human rights lawyer and activist Parvez Imroz, who talked about the impunity enjoyed by the Indian Army in J & K, said that they have been taking over vast stretches of land in the state for their activities due to this. Imroz is the Founder-President of the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS) as well as the Convenor of the International People’s Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice in Indian-Administered Kashmir. He concluded the session by saying that the image of the country, built by generations of democratic leaders, was now being tarnished by the decisions of the current political dispensation.