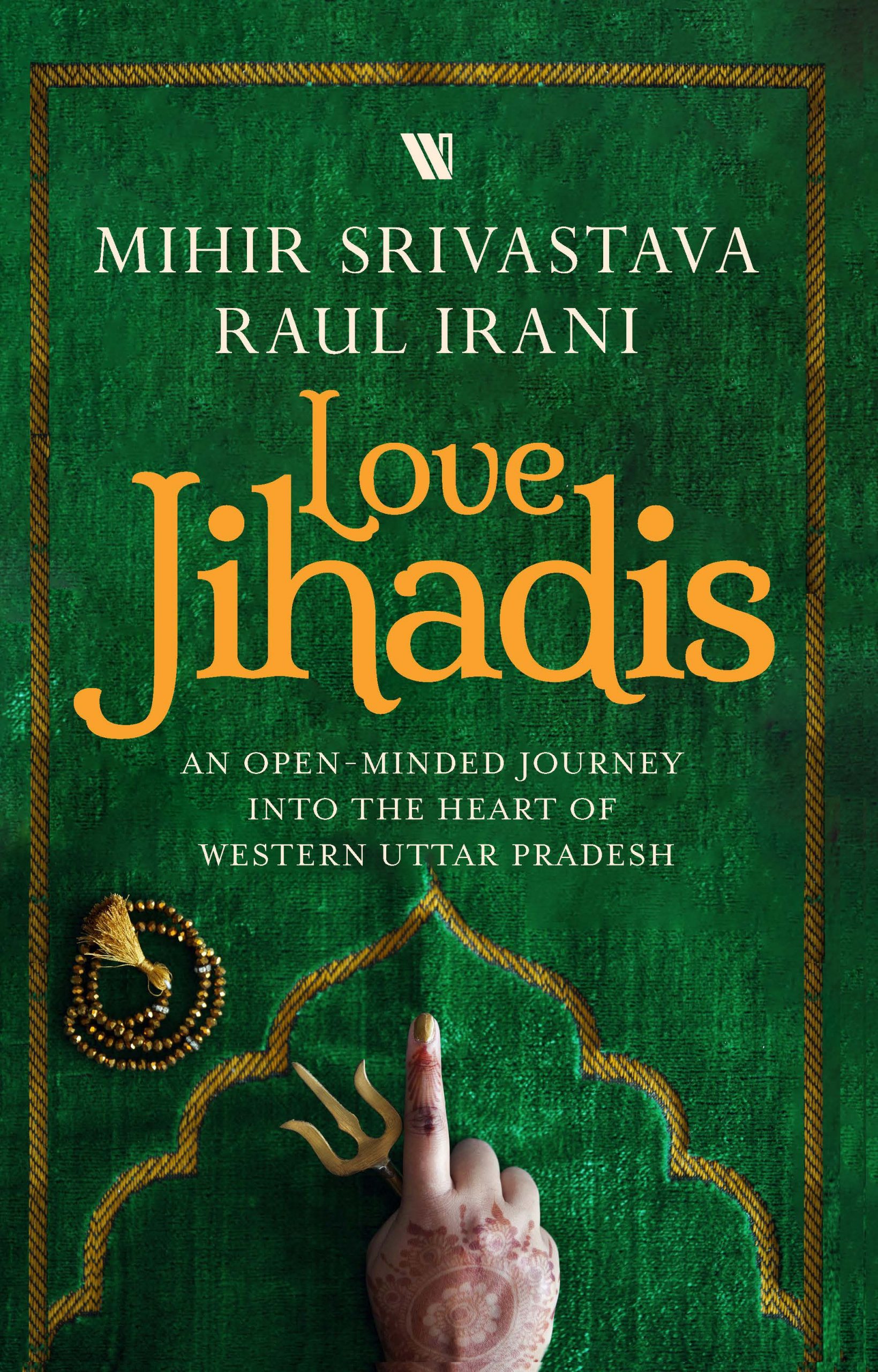

In this nuanced examination of the idea and reality of political ploys like “Love Jihad” and “Ghar Wapasi”, journalists Mihir Srivastav and Raul Irani present the many facets of increasing communal polarisation in Western Uttar Pradesh. Love Jihadis: An Open-Minded Journey into the Heart of Western Uttar Pradesh (Westland Publicatiobns, 2020) offers, on the one hand, an intimate political and psychological insight into those like Chetna Devi – the crusaders of communal mistrust, and on the other, an eye-opener into the daily tribulations and grit of the Muslim youth affected by these inflamed sentiments.

Following are some excerpts from the book where we meet Chetna Devi, the religious head of the Akhand Hindustan Morcha, also known as Yati Maa, who is committed to “save” Hindu girls from being “trapped” by “sensuous” Muslim men.

Meerut: Chetna Devi and the Hindu Army

Chetna was always focused when we spoke. It does not disturb her that her love for her fellow Hindus is fuelled by hatred for Muslims. Indeed, hatred seems to be the guiding force of her myopic worldview. Her hate is genuine, much like true love. She isn’t faking it for some political convenience. And I can’t help but empathise with her: she is so wrong, but her convictions are the gospel truth to her, and she is tormented by them every moment of her life. All this hatred has become her life force.

She explains her fear of living in a Muslim-majority India in various ways. There will be a Muslim prime minister, and that will almost instantly make Hindus refugees in their own country. She draws out this doomsday scenario with all the drama of a theatre performer. You might wonder, given the strength of her feeling for the victimised Hindus of the future, whether she could spare some of that empathy for the Muslims of the present. Attacked for the most frivolous of reasons, now that the BJP is in power, Muslims in India today certainly feel they are refugees in their own country. But, no. That was asking Chetna Devi for too much.

We politely tested her hypothesis in the light of history. Gently, we reminded her of certain facts: that India had been ruled by the British and before them, by Muslim rulers for a good millennium. Neither the British nor the Muslims had been the majority community; on the contrary, they had been minuscule minorities. Yet, they managed to rule. And while their various reigns had mixed results, Hinduism not only persisted, but assimilated various other influences over the centuries while retaining its essential character.

‘Islam is a problem,’ she persisted, baffled that we could not see this simple fact that she was trying to hammer into our minds. ‘See what’s happening all over the world. Muslims are always part of conflict. Terrorism and Islam are synonymous. This is an existential battle for Hindus. By 2030, Muslims will be the majority community in India, and Hindus will be slaughtered on the streets,’ she reiterated.

Also read | Love Jihad: Reality or Conspiracy to Oppress

History shows that this is unlikely to happen, we pointed out. ‘But what if it happens? We can’t say, sorry, we’re not prepared, and ready ourselves to die. We should be able to defend ourselves against any eventuality. And to do that, we have to start preparing now.’ Her demagoguery is not born out

When the tea and snacks arrived, Chetna’s demeanour changed again. She became the most generous host; we shared jokes while sipping tea. The snacks were wholesome, almost a meal, and we were always hungry.

Her husband looks much older than her: fairly frail, with a moustache on his bony face. He has a deep, husky voice, and over the years, has become a keen believer in his wife’s convictions. He interrupted her often, adding unnecessary details to what she said. Chetna ignored him sometimes, and continued with her sermons as he simultaneously tried to substantiate his wife’s arguments.

She has many arguments, many stories to tell. A good orator, she speaks in her drawing room the way she would speak from the podium to a gathering of supporters. Chetna has narrated this story hundreds of times, and each time, she reinforces the ideas for herself as much as she does for others, so there is no escape. She is a captive to her own worldview.

Chetna claims to know history. The people of the monotheistic religion, she says, have a fairly aggressive history of propagating their faith. In India, they are waiting for the right moment to strike. A sort of clash of civilisations will ensue, and the weak Hindus should be ready to face the challenge by arming themselves in preparation. Her vision of the future is dark and her fears are real—if you don’t agree with her, that’s your problem. She’s not seeking support or approval. It’s a question of life and death.

The first formidable challenge to Chetna’s worldview came from her own father. He was also a lawyer in Meerut and many of his clients were Muslims. Chetna started her legal practice as an apprentice to her father. She was rude and harsh to her father’s Muslim clients and many of them were justifiably antagonised. Her father tried to counsel his rebellious daughter, with little success. Finally, he asked her to leave. She stayed away from her father for many years, with no contact between them, despite living in the same town. But towards the end of his life, she claims, her father did understand what she was fighting for.

Her leg was in a plaster and she was in pain, but Chetna drove us to her ashram to meet her guru Narsinghananda Saraswati. The ashram is an hour’s drive from her home. Its closest town is Hapur. A serpentine, metalled road led us to Dasna Devi Mandir, the ashram. A banner tied across the entrance states in Hindi: ‘This is a scared place for Hindus. Muslims are not allowed.’

Outside the gate, as Raul was photographing the absurd and hateful banner, we met a Muslim man wearing a skull cap. He identified himself as a local trader. ‘We lived here happily for centuries, he said with anger and contempt. ‘This is what they have to tell us. They came (referring to the ashram) here and now, want to make us fight. Love and brotherhood are things of the past.’ He was dejected. ‘What’s the point of taking pictures?’ he asked. ‘Y promoting them. They’re an insult to me and you, to every Indian.’

I worry that, though he has every reason to feel offended and hurt, this sense of dejection and resignation to the new reality of India will only embolden people like Chetna. But what can he do? The community’s survival tactics, as counseled by its elders, is to lie low and swallow insults.

Muslims tell the young ones, their sons and daughters, to negotiate this tricky phase as frogs do when they hibernate in the winter. No parent wants their son or daughter to be caught in the crossfire and die an early death. To survive is the most basic need. When you know your adversary has political patronage, you try to avoid conflict. Some hot-blooded young men don’t subscribe to this passivity, but they are few and far between.

Chetna is satisfied that Hindus—the underdogs—have been able to instill fear among Muslims. To her, though, this silence is ominous: ‘They are busy multiplying,’ she said.