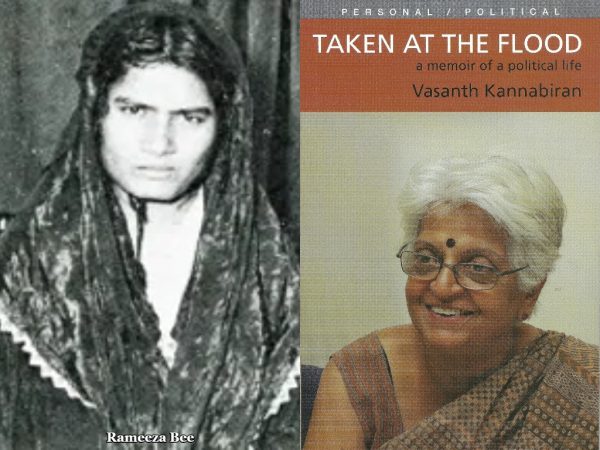

Noted feminist, activist and writer, Vasanth Kannabiran, was witness to, and participant in, Andhra Pradesh politics and civil liberties during the tumultuous decades of the late 1970s and 1980s, both as part of the women’s movement, and through the legal engagements of her husband, the legendary K.G. Kannabiran.

The dark days of the 1975 Emergency; the uneasy calm in the aftermath of communal violence in Hyderabad in 1984; the thrill of electioneering; the historic peace talks between the Naxals and the government; the anti-arrack movement; Rameeza Bee and Mathura; alliances and networks across South and Southeast Asia—she was there, and she tells it like it was, in Taken at the Flood: A Memoir of a Political Life.

The following is an excerpt from the chapter “The Muktadar Commission” of the book.

The Muktadar Commission1

It was 1978, a year that marked many beginnings for the women’s movement in India. The Commission of Enquiry into the rape of Rameeza Bee2 was being held in a packed hall in Hyderabad. There was barely room to move. The air was heavy with anticipation. It was a court room setting with a witness box and a place for the accused, and about half a dozen lawyers. The crowd was mostly made up of men from the city, jostling to see what would happen. Trying to get a look at the victim. She had not been brought in yet. There was also a group of middle class women there, determined to survive the crush and the jostling and observe the trial. There was heavy police presence. After she was brought into the hall, Rameeza was asked to lift her veil so that the man who was appearing as a witness against her could look at her face and confirm: ‘Yes! It was her.’ And then go on to give a date and the name of a lodge. She would then lower her veil only to be told to lift it once again, a few minutes later, for the next witness. Each time the crowd would hold its breath in anticipation and then a titter would ripple through the hall. Every time, the response was the same. It was systematic, deliberate, serial public rape.

Rameeza Bee was raped in 1978 by four policemen, and her husband, Ahmad Hussain was beaten to death for protesting. His death had triggered widespread violence in the city. Hyderabad was on fire.There was rioting, the police station was burnt down, records were torched, curfew was declared with shoot-at-sight orders, several people were shot dead in the police firing and then, finally, a Commission of Enquiry was constituted. Justice K.A. Muktadar was conducting the hearing. Exposed for the first time to the profound suffering, the lived realities, and the denial of justice to poor Muslims, he was shaken by the ugly truth that confronted him.

What was particularly troubling about this case for me was the glamour that surrounded the rape, the prurience, and the complete lack of defence for a woman who had been sexually assaulted and then accused of prostitution. The police declared that Rameeza Bee’s husband was a pimp, so there was no case. And yet, the city was shaken up by his death and her rape. There was no communal angle to the riots but several well-to-do Muslims were alarmed enough to sit up and take an interest in the case. Although there was a superficial sense of pity for the woman, the manner in which it was expressed was obscene. One ‘patron’ gave her his wife’s jewellery and a lace burqa so that she could look ‘decent’. That her husband had just been killed and she was grieving was no one’s concern. He also generously offered to marry her. Another nawab said he would keep her at his guest house! Indeed, the quality of mercy is not strained! Instead, Rameeza Bee was brought over to our house and my husband, Kannabiran, who was representing her, requested us— my friends and fellow Stree Shakti Sanghatana members: Veena Shatrugna, a doctor; K. Lalita, a sociologist and an ex-member of an ML party; and political scientist, Rama Melkote—to talk to her. What struck me then, as now, was the utter simplicity of her recital. No tears, no anger, no hysteria. Just a flat narration of that night—one policeman after another came in and raped her. One constable, however, was kind enough to give her a mug of water to wash herself. She had lost her husband but there was no space or time for grief. A man had been beaten to death for protesting the assault on his wife but it was the rape that had taken centre stage. I remember Susie Tharu, who was a close friend, teacher and member of the Stree Shakti Sanghatana, insisting, time and again, that we not forget that a man had lost his life as well.

Rameeza’s case brought home the realisation that if four good men and true, were to stand up in a witness box in court and point towards me and say that they had paid to have sex with me on such and such day at a lodge, I would be held guilty. No alibi, no register, no proof, no witness would be needed to prove that I was not a prostitute. For those of us who were just beginning to coalesce as a women’s group, it was a brutal orientation to the patriarchal nature of the law. We graduated with the Mathura anti-rape campaign which gained momentum in 1979.3

The prejudice against prostitutes and entrenched moral attitudes run so deep that even the Communist Party of India (CPI) refused at first to be associated with the enquiry in Rameeza Bee’s case. It quickly changed its mind when it saw the huge public mobilisation. In spite of the unbiased findings of the Muktadar Commission, the case was transferred to the neighbouring state of Karnataka in order to ensure that the policemen got a fair trial! Meanwhile, Rameeza was arrested several times on charges of procuring and, predictably, failing to identify the accused. The judge was reported to have been well entertained by the police to ensure their men got a fair trial! It was a typical heads I win, tails you lose situation.

In a sense, Rameeza Bee’s case and the Muktadar Commission catalysed the ‘birth’ of our group, the Stree Shakti Sanghatana. Till then, we hadn’t come together formally as group, but that enquiry was like a breaking-in for many of us, revealing what it meant to be a woman. How seldom fundamental rights or the rule of law came into play was an eye-opener for many of us. That the law and the police can be so unashamedly impervious to issues of violence was another practical revelation that was completely shocking. For me, personally, this case brought on the realisation that there is no dramatic shattering of glass, no loud screams or the clash of cymbals in the background when rape happens. No. Gang rape can be a series of drunken men coming, one after another, to finish their ‘business’ while the woman quietly murmurs, ‘How many more are there?’ And that a rapist can, in fact, give her a mug of water to wash herself—an act of ultimate kindness. Valuable lessons were learnt during the Muktadar Commission hearings which prepared us for the Mathura campaign.

1. In 1978, the Andhra Pradesh government appointed Justice K.A. Muktadar to head the Commission of Inquiry that probed the matter of the rape of Rameeza Bee and the custodial death of her husband.

2. Rameeza Bee was brutally gang-raped by a group of policemen in Hyderabad in 1978.

3. In 1972, Mathura, a 16-year-old tribal girl, was raped by policemen while in custody, in Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra. In 1979, after the verdict that acquitted the accused, lawyers Upendra Baxi, Raghunath Kelkar and Lotika Sarkar wrote an open letter challenging the verdict. Following this there was a countrywide mobilisation of activists, feminists and others protesting the verdict, and this was the beginning of a national anti-rape campaign.