One positive outcome of the national lockdown is that it has demonstrated to the Muslims of west Uttar Pradesh the virtues of simple, low-cost weddings, without the customary pomp and show typical of most parts of India. So thrilled are they at their experience that they want a social movement to reform customary Muslim marriage practices in the region.

The introspection among Muslims regarding weddings was sparked by the Union government’s decision to impose the lockdown from 25 March, with just four hours of notice. That decision threatened to abort the weddings already scheduled. Not only did it seem impossible to take the baraat or wedding procession from one place to another, even the customary wedding feast was deemed a strict no-no.

It is impossible to identify the person who sought permission from the administration to conduct his or her child’s wedding. Anecdotal accounts will have us believe that there were quite a few applicants. They were granted permission subject to their acceptance of the stringent norms regulating physical distancing, such as the number of people who could accompany the groom to the bride’s place. And wedding feasts for anyone other than family members were ruled out.

At one stroke then, the traditional Muslim wedding became a low-cost affair. The groom and his family would go to the bride’s residence, conduct the nikah, the Muslim wedding ceremony, and share a meal. In two hours or so, the groom and his parents would be speeding back to their residence, with the bride obviously.

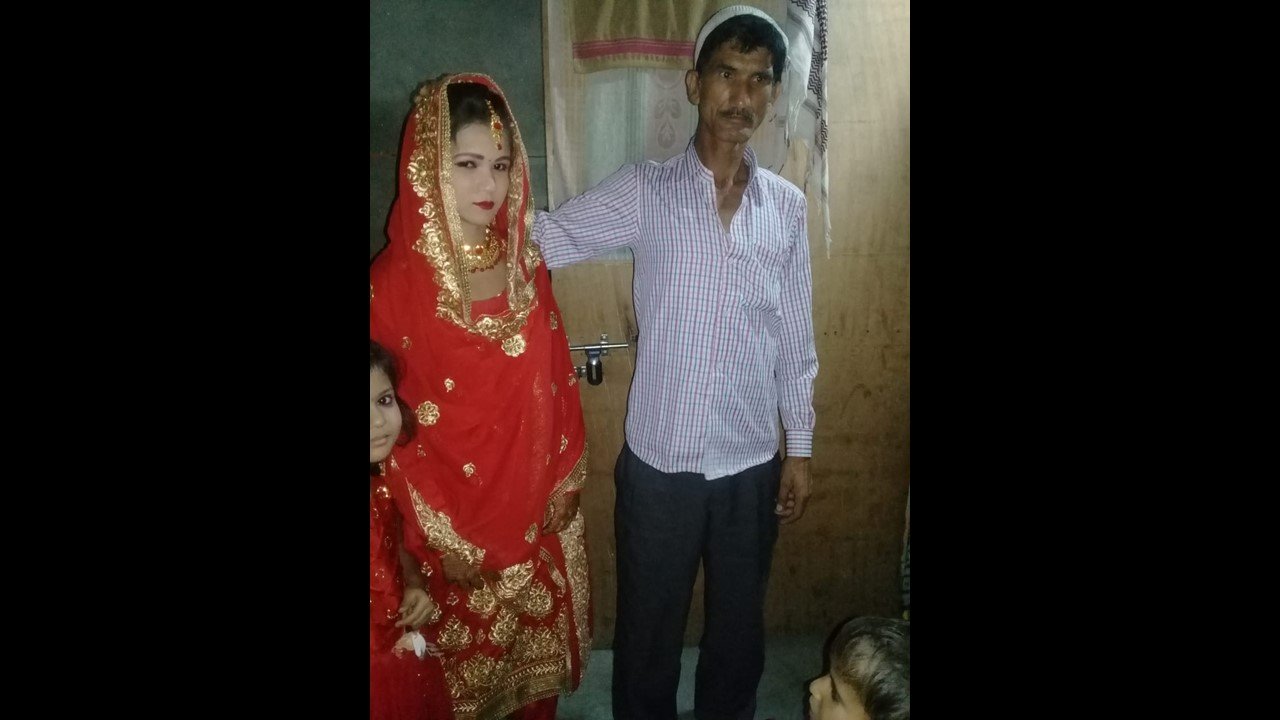

This was how Dilshad Saifi, an advocate in Shamli city, said the marriage of his brother, Irshad, was conducted. Irshad had been scheduled to marry a girl in Budhana, about 24 km from Shamli, on 20 April, six days after the lockdown was to end. Much to their dismay, the lockdown was extended, prompting the Saifis to send a message to the girl’s family: let us conduct the nikah, forget the frills-and-feast wedding.

The Saifis secured the administration’s permission to take out the baraat, which was to comprise a grand total of five—the driver, Dilshad, his parents, and, obviously, Irshad. They went to Budhana, where the nikah ceremony was witnessed by just eight members from the girl’s family. The Saifis returned home with the bride on the same day.

Dilshad said the family had budgeted Rs. 5 lakh for the wedding. Rupees five lakh?

In west Uttar Pradesh, the entire neighbourhood expects to be invited to a wedding reception, as do family friends and relatives. There are expenses incurred on giving gifts to relatives, clothes for instance. The lockdown enabled the Saifis to save Rs 5. lakh, with which they opened a fixed bank deposit in the name of Irshad and his wife. “It is infinitely better to start off the couple with Rs. 5 lakh, than to blow away the money on a lunch or dinner,” Dilshad said.

When middle class families such as the Saifis opted for the no-frills wedding, those in lower income groups too followed suit. Their problem was that they lacked the ability to apply online for permission from the district authority. Community and political leaders stepped in to help them.

Their support turned the lockdown wedding into a rage, an unprecedented social phenomenon.

Take Shamli’s Shamim Qureshi, who deals in worn-out tyres that are utilised for firing brick kilns. His monthly income is around Rs. 12,000. Before the lockdown, Shamim had been negotiating the date of marriage of his sister, Tarannum, with a family in Muzaffarnagar. The two sides had tentatively agreed to conduct the wedding before the month of Ramzan was to begin on 24 April.

As the lockdown shuttered people inside their homes, the groom’s family reached out to Shamim: “We will do our son’s nikah with your sister. We do not want anything else.” On 20th April, the groom and another three, including the driver, arrived at Shamim’s residence at 4 am. By 6 am, after the nikah and a hearty meal, Tarannum was on the road to her sasural. “I spent Rs. 2,000 on food and Rs. 5,000 on her clothes,” Shamim said.

The bride’s family, typically, comes under immense social pressure to hold a gala wedding. The meaning of gala, obviously, varies from one income group to another. Shamim said Tarannum’s wedding in normal times would have cost him at least Rs. 1 lakh.

When I repeated the figure in an incredulous tone, Shamim listed the types of guests he would have had to call—all his relatives, all residents of his mohalla, and all those who had, in the past, invited him to weddings in their families. “If I were to miss out any, they would go around saying, ‘Shamim dawaat khata hai, dawaat deta nahin (Shaukat attends feasts, but does not host one)’,” he said.

Shamim said the lockdown wedding model is what the Muslim community should adopt. He, in fact, adhered to this model for marrying his two brothers, who had been betrothed before the lockdown to two sisters in Charthawal, located about 35 km from Shamli. Shamim turned to Javed Jang, a farmer-politician, who helped him apply online for the requisite permission, which was granted.

On 24 April, the baraat of Shamim’s two brothers left at 2 am for Charthawal, in two jeeps, each with two persons and a driver. The newly-weds were back in Shamli before sunrise. “The lockdown has come as a boon for those whose income is low,” Jang said. “The no-frills wedding has liberated them from the social pressure of spending money on weddings.”

Many took the name of Arif Mansoori, who is in Shamli’s transport business, as among those who helped organise a substantial number of lockdown weddings. Mansoori’s father is a prominent leader of the Jamiat-Ulema-e-Hind, a Muslim organisation with a historical significance and national footprint, in the area.

“I alone have secured permission for at least 100 families to conduct weddings during the lockdown,” Arif said to me. Finding the lockdown a relief from the burden of wedding expenditure, several low-income families found partners for their children and promptly organised their nikah. “Some of us raised money for those who wished to take advantage of the lockdown to hold low-cost weddings,” he said.

Arif explained the phenomenon of lockdown wedding in a language employed to describe the spread of the Coronavirus: “The lockdown wedding began with a family, then its neighbour thought the idea was great, the two turned into four, then the four turned into eight… The lockdown wedding has gone viral,” he said.

The phenomenon of lockdown wedding is not confined to Shamli alone. In Jalalabad, Ashraf Ali Khan, whose family once held the zamindari rights in the area, said at least 50% of all marriages during the lockdown were arranged and solemnised in this period. “The idea of no-frills wedding has caught on,” he insisted. Jalalabad’s current nagar palika chairman, Abdul Gaffar Choudhry, agreed: “Only 20 per cent of those who had already scheduled marriages decided to postpone them. The rest went in a group of two or three to do the nikah of their children.”

When I spoke to Ashraf Khan, seated with him was Altaf Rao, who had come to Jalalabad from Bhesani, a village dominated by Rajput Muslims. Rao said, “In Bhesani and its adjoining areas, there must have been 200 lockdown weddings. People would go at night and return with brides in the morning.” Rao said the no-frills wedding model marked a radical departure from the dominant norm among Rajput Muslims to host ostentatious weddings.

The lockdown wedding was also a rage in Nakur, a town in Saharanpur district. Its nagar palika chairman, Shahnawaz Khan, said, “If there were 100 weddings in April and May last year, we must have easily witnessed 200 this year.” He said the number of weddings zoomed because the daily wage earners sought to take advantage of the lockdown. “In the lockdown, no one could invite people for the wedding. The cost of wedding dipped. Marriage is one of the important causes for the indebtedness in the area,” Shahnawaz said.

In Thanabhawan too, according to Abbas Zaidi, who is in the dairy business, around fifty Muslim marriages were solemnised during the lockdown. “The lockdown deprived the poor of daily wages. But it also enabled them to save money they would have had to spend on weddings,” Zaidi said. At play was also Islam’s emphasis on austerity. “It provided an ideological justification for people to support low-cost weddings,” Zaidi said.

What is puzzling was the decision of wealthy Muslims to opt for the lockdown wedding model. “Their motivations were two,” said Ashraf Ali Khan. “One, the economic uncertainty had them think that it would be wise not to deplete resources on weddings. Two, parents thought they must marry off their children, for who can tell whether or not they would survive the novel Coronavirus.”

The second factor was exactly what drove Shehzad Qureshi, who operates a meat export unit at Dera Bassi, a satellite town of Chandigarh, to organise the nikah of his three brothers in Jalalabad. These were staid, simple affairs, in contrast to the norm among the Qureshis, perhaps the only Muslim social group to have registered economic mobility in recent years, to hold pretentious weddings. They are known to publicly display the jewellery and cash gifted to the couple, even furniture and cars. Their wedding feasts are lavish.

Shehzad said his brothers too would have been married with flamboyance, but the Coronavirus nixed the family’s plan. He said his father felt so vulnerable in the wake of the Coronavirus that he insisted on marrying all his sons during the lockdown. Between 21 April and 23 April, the nikah of all his three brothers were performed, each marriage party comprising two or three people. “Had there been no Coronavirus, we would have spent at least Rs. 75 lakh on their weddings. You know how we are,” Shehzad said.

There was not a hint of wistfulness in Shehzad’s voice during our conversation. He, in fact, said the lockdown wedding was a revelation to him. “We can utilise the Rs. 75 lakh we saved in helping the poor and building assets for them.” Displaying the enthusiasm typical of new converts to an idea, Shehzad said, “From now, we must tread the path of austerity. Our life would be so much the better.”

It is seemingly a mystery why the lockdown wedding became a rage only among the Muslims. Samajwadi Party leader and academician Sudhir Panwar said, “For one, Hindus in the region rarely hold weddings in March-April, which is the harvest period. For the other, you need at least a month to organise Hindu weddings. Pandits are asked to choose an auspicious day, and then plans are made around the date.” In other words, the lockdown period did not give elbow room for Hindus to organise no-frills weddings.

By contrast, the idea of auspicious day has no pull on Muslims. But there is also the economic factor driving the lockdown wedding, evident from the attraction it holds for the poor among the Muslims. “The Hindus, on average, are more prosperous than Muslims. The opportunity to hold low-cost weddings, without getting socially stigmatised, had relatively less of an allure for the Hindus,” Panwar said.

As India rolls back the lockdown and restrictions on physical distancing are eased, the no-frills wedding model continues to win converts among the Muslims of west Uttar Pradesh. On 7 June, Mohammad Shoaib, who is in the embroidery business, hosted a wedding feast for his daughter that was attended by 30 guests, inclusive of family members. The menu was vegetarian. Shoaib is estimated to have spent Rs. 3 lakh on the wedding of another of his daughters in October.

On 8 June, Mohd Nazim Mir, who runs a saloon in Shamli, married two of his nieces. On the same day, in Jalalabad, Mukhtiar Zaidi was delighted to have participated in the no-frills wedding of his sister. Employed in a private company and still single, Mukhtiar said, “That is the way to go. Why should I become a burden on the family of the girl whom I would marry?” Noble words these. Perhaps a foundation upon which community leaders can build a social reform movement.