A translator of Urdu fiction and prose, Tahira Naqvi has taught Urdu at Columbia University and now heads the Urdu programme at New York University. She has translated Chughtai’s short stories, novels and essays. Talking about Chughtai, who she fondly calls Ismat Apa, is one of Naqvi’s favourite subjects. She has also translated Chughtai’s last and lesser known novel, Ek Qatra-e-Khoon.

In this conversation with Daniya, she talks about her love for Urdu fiction, the women in Chughtai’s stories, her journey into the world of translation and a lot more.

Daniya Rahman (DR): How did your journey into the world of Chughtai begin?

Tahira Naqvi (TN): My journey into the world of Chughtai, or Ismat Apa as I like to call her, began when my aunts first read to me from Shama and Afshaan, by AR Khatoon. Later, when I could read these works myself, I found myself tangled up in Urdu fiction for life.

In 1983, I found myself in a small Connecticut town, a wife, a mother, far removed from the world of Urdu fiction. But literature has a way of embedding itself into the very pores of one’s existence. With my youngest of three boys now in daycare, I decided to return to reading Urdu fiction again. During one of our annual trips to Pakistan I searched for and found what I was looking for in Lahore’s Urdu Bazaar. I brought back Manto, Ismat Chughtai, Premchand, and Pakistan’s Bronte sisters, Khadija Mastur and Hajira Masroor, and of course copies of Shama and Afshaan.

One day I just decided to translate Swaang (Mimicry), a Premchand story, and impulsively sent it to Translation, a journal published in those days by Columbia University. It was accepted. I have often been asked why I began translating and why Premchand first. I have no real answer.

I then took up a story by Manto, and then another, both of which I sent to Professor S.M. Naim’s Mahfil: The Journal of South Asian Literature. He published them. I didn’t know what I was going to do with the other stories I was translating now, in that small Connecticut town where people hardly knew of the existence of a country called Pakistan. The story is long and for another time, but the Manto collection finally found a home with Najam Sethi’s Vanguard Publications. He suggested I talk to Professor Leslie A. Flemming, a Manto scholar, the first in the United States, and request her monograph on Manto for our introduction to the collection. We corresponded. Professor Flemming graciously and happily gave us her wonderful monograph which became part of the title of my collection: Another Lonely Voice: The Life and Works of Saadat Hasan Manto.

Later, as we spoke on the phone, she asked, “What now Tahira?”

“What do you suggest Leslie?” I asked.

“Why don’t you try translating Ismat Chughtai,” she said. “She’s never been done before. But she’s difficult.”

I wrote to K.A. Abbas, whom we lovingly called Mamu Bacchu, and who was my husband’s maternal uncle, and also a good friend of Ismat Apa, and asked if he would introduce me. Anxious to get copyright permission, I sent him a translation of Do Haath (Two Hands) and requested that he pass it on to Ismat Apa. I finally heard from her, many many months and two other letters later, and she didn’t say if she had liked the translation or not, only that she thought it was difficult to put the work of one language into another. She also discussed in detail the context of Do Haath. In a third letter she gave me blanket permission to translate her work.

And that was that. I’ve never looked back. The story of how I ended up with Ritu Menon and Kali for Women, now Women Unlimited/Kali for Women, is a story of serendipitous coincidences and happenstance, a tale for another day.

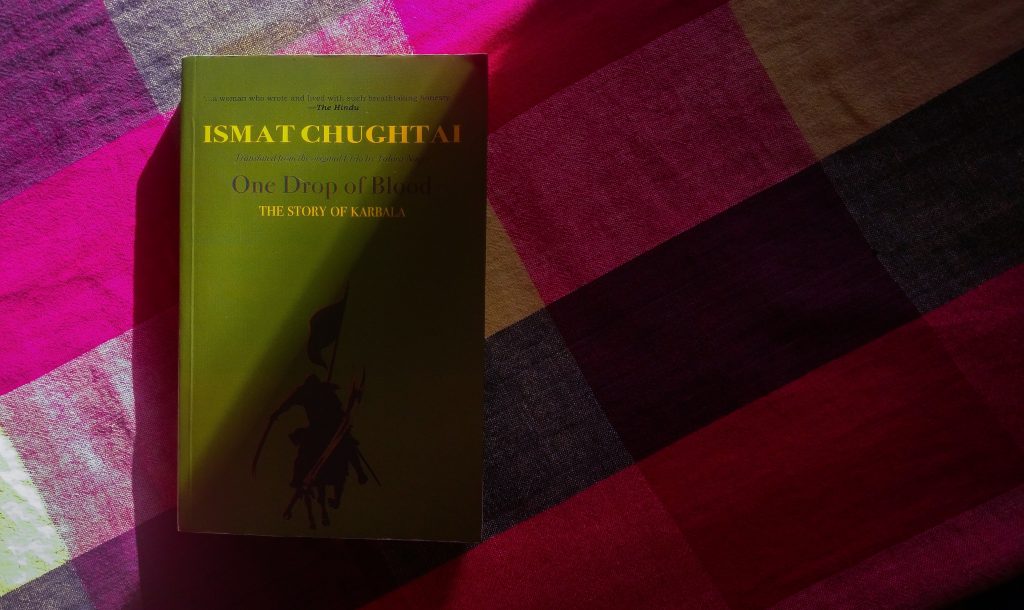

DR: Ek Qatra-e-Khoon, the book is not often mentioned when one talks about Chughtai’s work. Why do you think that is? What led you to translate this book? Was it only because you wanted the book to reach a wider audience?

TN: Qatra has never received the attention it deserves. Readers of modern fiction, especially those accustomed to Ismat’s particular oeuvre, might have ignored it because of its heavy religious content. Some, misled perhaps by a superficial reading, found it wanting in terms of the verve and fervour that such a story might demand. One particular critic went so far as to call it a “damp squib”; others may have wondered about Ismat’s real intent. Most bibliographies comprising her work—novels, short story anthologies, essays, reminiscences, etc.— fail to mention Ek Qatra-e-Khoon.

I have been translating Ismat since 1984, and each time Qatra hovered as the next project; and each time I passed it over for some other work of hers. In 2018, I read Akbar Hyder’s Karbala, was deeply moved and inspired by his insights on the experience of mourning and its relationship to literature. What a wonderful book on Karbala, I thought, and how important to make it possible for readers interested in the subject to read Ismat’s novel about it. The desire to take it up was compelling and I began the translation slowly and hesitantly. With each page I worked on, my resolve faltered. Reading the novel closely, staying with each paragraph for long periods of time, returning to re-read and review, all this stirred deep feelings anchored in my own experience of mourning, for the tragedy that befalls Husain and his family. Each engagement with the written page became a majlis for me, an interlude of mourning that we, Shias, participate in from childhood. Every word is engraved in our consciousness as an act of absolute remembrance and sorrow. I would read, weep, and translate. I felt as though Muharram, the period of mourning, was never going to end.

But the story also provided the impetus to continue, for there was newness here despite familiarity, moments that were revelatory, a heightened sense of reality. Karbala became a place populated with not just these godly, sublime individuals, but a fearsome, cruel desert, a battlefield where real men, women and children suffered in the most dreadful way at the hands of a savage, unrelenting army, led by men whose conscience had abandoned them. For the first time I experienced, through Ismat’s story-telling and her language, an atmosphere and mood that embellished decades-old images cast in history and tradition. It is true that the novel, by her own admission, derives from the marsiyas of Mir Anis, long and elegiac accounts of the tragedy, but Ismat transforms the high art of poetry into the everyday pathos of real time, real people with real emotions.

DR: Could you talk about the different women in Chughtai’s stories, from Lihaaf to Tehri Lakir, to Saudai and even Ek Qatra-e-Khoon?

TN: The subject of Chughtai’s women is not one to fit into one or two paragraphs. It merits a book. For the purposes of this conversation I will go over a few salient points.

Chughtai writes about women of every class and every age. With perfect ease and a remarkably skillful and intuitive approach, she explores their psychological motivations, their roles in the society and class of which they are a part, and portrays them with such realism and honesty that we recognise them all as familiar, believable and worthy of our attention and compassion. She addresses taboo subjects like rape, sex outside of marriage, sexual exploitation, teen pregnancy, women in love, women and sex, women in love with other women, the evils of a patriarchal system, the mistreatment of women by women, the exploitation of women by men and women in the film industry of Bombay.

In stories that have been largely ignored because they don’t fall into any of these molds, Chughtai explores the lives of young college-going women on the cusp of sexual freedom, standing at that precarious yet exhilarating place where feminism was waiting in the wings for them. Jhirri main se” (Through a Crevice), Puncture, Safar Mein (While Travelling), Aik Shauhar ki Khatir (For the Sake of a Husband), Parde ke Piche se (From Behind a Curtain), Dhiit (Obstinate One), are examples, and there are some plays as well — Saudai and Saamp, for instance, in which Chughtai deftly explores this subject. These women form the epicenter of the tension between tradition and independence, collectivism and individualism.

Of the older characters, Nanhi ki Nani, Bichu Phupi, Kubra’s mother, Bi Amma, in Chauthi ka Jora (The Clothes for Fourth Day), the abandoned mother in Jarein (Roots), Gori Dadi in Mughal Baccha (a rewrite of Ghoonghat), Masooma’s mother in the novella Masooma, to name a few, are memorable. These are women who suffer but despite the odds stacked against them, don’t give in without a struggle.

The younger women in Chughtai’s stories, Masooma, Kubra (Chauthi ka Jora), Qudsia Khala (Dil ki Duniya), Asha (Ziddi), Begum Jaan (Lihaaf), Rukhsana in Amar bel,” Gori in Til (Mole), Rani in Do Haath, and Shamman in the novel Terhi Lakir, to name a few, are from all walks of life and also a stubborn lot, and in spite of the wretchedness of their lives, the financial burdens they must bear, the stifling social constraints they must grapple with, they make a break and seek new ways to address their problems.

Other characters, the orphan in Saudai,( The Mad One), the maidservant in Badan ki Khushboo, (Fragrance of the Body), the sweeperess Gori in Do Haath (Two Hands). Asha in Ziddi, (Stubborn One), form a class of their own in Chughtai’s oeuvre, a testimony to the writer’s commitment to drawing attention to women’s lives from every segment of society.

The youngest characters in Chughtai’s stories are Nanhi in Nanhi ki Naani, (Nanhi’s Grandmother), Gainda in the story of the same name, the narrator in Lihaaf, the narrator in Dil ki Duniya, Kubra’s younger sister in Chauthi ka Jora, and Shamman as a child and then a young girl in the novel Terhi Lakir (The Crooked Line). These young girls are some of Chughtai’s most poignant and complex characters and drawn with a sensitivity and insightfulness that takes one’s breath away.

It is generally said and is the case for the most part that Chughtai’s female characters come from the Muslim families of U.P. and belong to every class and social status imaginable. But she has written about Christian and Hindu women as well with the same probing and intuitive point of view. Asha in Ziddi, Chandni in Saudai, and Madan in Kunwaari (The Virgin), are the ones that immediately come to mind. These characters represent a vast range of psychological profiles and temperaments, convictions and mindsets that Chughtai explored.

Chughtai’s preoccupation with family dynamics, her sensitive and insightful exploration of relationships between family members, her keen observations of relationships among and between women, culminate in the way she draws her characters in Ek Qatra-e-Khoon (One Drop of Blood), her last and, by her own admission, her most important work. Although based on the historical events related to the tragedy of Karbala, the narrative is a novel, a story told by a writer who had mastered the art of giving women a voice. She creates flesh and blood female characters — Zenab Bint Ali, Fatima, her mother and daughter of the Prophet, the young new bride Kubra and, Hind, Shireen, Umme Laila, the wife of Hussain Ibn Ali, Hussain’s daughter Sakina — endowing them with a humanity and persona that turns them into real daughters, sisters, mothers and wives whom we can easily identify with and relate to. Once again, Chughtai focuses on the lives of women, choosing Hussain’s family as her context, highlighting the role these women play in the last stand at Karbala.

DR: As someone who has translated so much of Chughtai’s work you must have encountered different versions of Chughtai herself. Could you tell us more about it?

TN: Oddly enough, Chughtai remains the same. I easily recognise her in Ek Qatra-e-Khoon, her last novel, and find myself saying, “Well, here she is, again, with her master strokes.” But she does spring surprises on me with the range of her themes, the manner in which she approaches women’s lives, the courage with which she wields her pen, and I sense the vast embrace of her art and craft as a writer.

DR: I read an article where you said that translating is like colonisation,”but one where the translator as coloniser treads softly, noiselessly, so that he or she can see clearly and hear all, and then, in trying to make the text his or her own, become one with it.” Could you talk a little about the process of translating from Urdu to English, the difficulties, the impossibilities, the solutions etc.

TN: Again, this is a question where saying a little bit is like saying nothing, so I’ll summarise as best as I can. I’m a literalist, a translator who feels she doesn’t have the right to mess with the original more than is absolutely essential. It is true that Ismat’s style is unique in terms of its specific cultural and linguistic representation, the use of colloquialism and syntax that constitute the everyday speech of Urdu-speakers of all classes and regions, making it difficult to translate the technique and form of her literary output. However, we try. I have struggled with all of this and will not say it has been easy. Early on I developed the habit of never reading the story in detail before I began translating. The newness and freshness of the text, the element of surprise in terms of what is coming next, has always helped me by de-cluttering the moment. Also, I keep the rhythm of her writing afloat in my head when I’m working on a story or an essay, almost like the tune of a song. But there are always hurdles, snags, roadblocks, and impossibilities. Recently I translated a story packed with so many colorful expletives peppering the speech of the female characters that I felt frustrated and stumped. This was the hardest thing I had done! But one learns to make compromises and find equivalents that won’t take the reader away from the near-perfect socio-cultural impact Chughtai has created. Finally, there comes a moment when you put away the original and look at the translation as the only thing that matters. A finished, completed work.