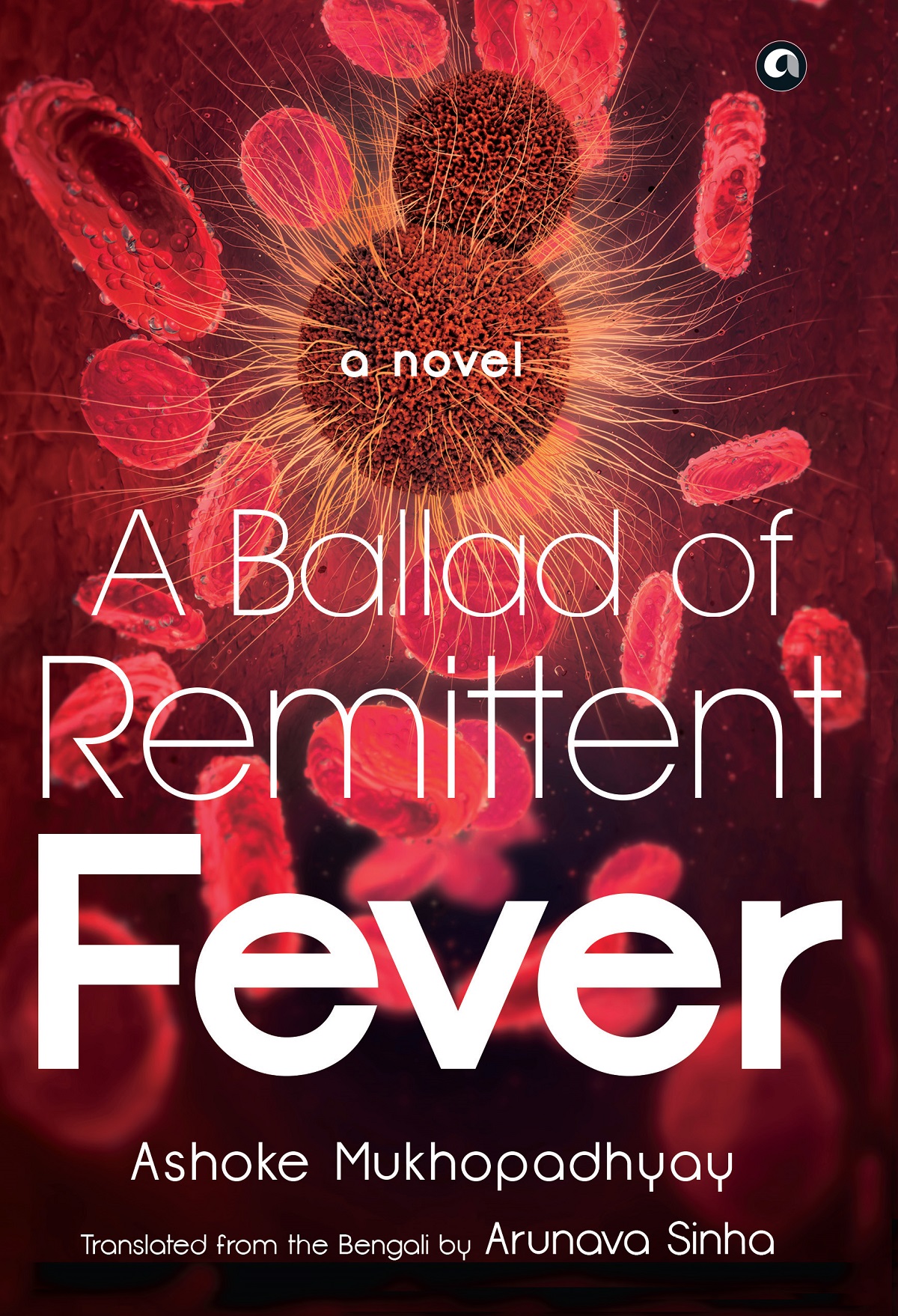

Written by Ashoke Mukhopadhyay and translated into English by Arunava Sinha, A Ballad of Remittent Fever is a story of four generations of doctors from West Bengal. The book deals with the world of medicine and the ordinary miracles performed by physicians in the course of their daily lives — all while grappling with deadly diseases such as the plague, cholera, typhoid, malaria, and kala-azar caused by viruses, bacteria and other infectious organisms.

The book was originally published as Abiram Jwarer Roopkatha.

The following is an excerpt from the chapter “A Discovery” of the book.

Dwarika remembered; it was like several doors and windows being unlocked in his memory. Hirabai, of the wondrously mellifluous voice. Her repertoire included numerous songs some of which he knew, and others which were unfamiliar to him. Listening to her sing was like being transported to the mountains or to a riverbank—a heavenly pleasure. But Hirabai lived in Lucknow. Yes, Dwarika remembered now, he had seen this muscular man before, it was Kishenji, Hirabai’s guardian for all intents and purposes.

Kishenji said softly, ‘Hiraji is in Calcutta. She is not keeping well…she sent me to you…if you would be kind enough to pay a visit…’ His voice trailed off.

‘Very well,’ said Dwarika and walked with his visitor to the door. Kishenji requested him to join him in his phaeton, but Dwarika preferred his own brougham.

It did not take long to reach Janbajar.

It was obvious that Hirabai was very ill. She was lying in bed, dark circles under her eyes, all her hair turned to white. Shorn of jewellery, she was looking even more pale. She tried to sit up in bed when Dwarikanath entered but failed.

‘I think my hour has come, Daktar saab…’ Hirabai’s voice had changed, its silken quality gone. It was not only indistinct but also harsh.

‘Why, what is the matter?’

‘I’m bringing up blood.’ Hirabai looked wan. ‘I think I have consumption, Daktar saab…blood comes out of my mouth when I cough…fresh blood, red…’

‘Bleeding from the mouth does not necessarily mean tuberculosis, there can be many reasons.’ Dwarikanath scanned Hirabai carefully as spoke, working out a course of action in his head.

Bleeding through the windpipe was termed haemoptysis. What were the possible causes? Dwarika tried to list them in his head. A wound in the lungs or trachea from an injury could be responsible, or it could be just an inflammation of the lungs, or even cardiac trouble. Tuberculosis and cancer led to bleeding, too.

‘All the melody has gone out of my voice, Daktar saab…what is the use of living this way?’

The courtesan’s large eyes filled with tears.

‘Give me medicine that will make me die, I cannot go on this way…’ She started coughing. Incessantly. Kishenji held out a large bowl into which Hirabai, she of the honeyed voice, vomited blood. ‘This is the third time…’ she whispered.

Dwarikanath inspected the colour of the blood carefully. Dark, with a tinge of red. The colour suggested an existing condition in the heart valves—mitral stenosis. This disease made the veins in the lungs swell with the blood flowing through them, with the effect spreading gradually to the capillaries too. Much more blood remained trapped in the lungs than necessary. As a result, the serum and red blood cells entered the tissue of the air bladder and even the air cells causing haemorrhagic oedema. As the smaller blood vessels began to swell and tear, the bleeding began.

Hirabai was probably suffering from mitral stenosis then. Dwarika took his stethoscope out of his bag. As soon as he placed it on the courtesan’s back she grimaced in pain. ‘That hurts…’

There were bruises on her body, both in front and as well as back. After a glance at Hirabai, the doctor looked Kishenji in the eye. A piercing gaze. Kishenji left the room in silence.

Dwarika was hesitant to ask about the cause of the injuries, but they could be responsible for the bleeding. And yet knowing the cause was not very useful; for now he had to stop the bleeding. The treatment would come afterwards.

The patient was made to recline backwards. Talking was forbidden. Dwarika recited the essential requirements. The room had to be kept cool. She would have to have ice in her mouth. A bag filled with ice would have to be placed on her chest. Cooling drinks would have to be given at regular intervals.

What medicines could he use? Dwarika asked himself. Acetate of lead, hamamelis, and gallic or tannic acid—he would have to rely on these.

As he rose to bid goodbye to Hirabai, strains of a song drifted in from the next room. A bhajan in bhairavi with touches of tilak kamod in it. Extraordinarily melodious, sung with great passion. But why had the singer chosen bhairavi for this twilight hour? Dwarika was a trifle surprised but his feet were rooted to the spot; he couldn’t take a step. Every pore in his body was soaking in the music.

‘She’s like my daughter,’ said Hirabai. ‘Think of her as my daughter…Saraswati. She does have a name of her own, I think, but I named her Saraswati after she came to me.’

‘May I meet her?’

‘Yes, you may go inside…but she doesn’t like speaking during riyaz…’

‘I shall not attempt to talk to her… I shall just look at her and leave…’

‘Go on inside then…’

Hirabai’s personal attendant escorted Dwarika into the room. A thick sheet spread on the floor. A chandelier overhead.

Accompanists on the carpet. The singer was dressed in a knee-length skirt, bodice, and scarf. A momentary view of her face rang a bell somewhere. Was there was some resemblance to Rosemary Smith?

Dwarika suddenly recalled he had to see a patient in Bahir Simla in North Calcutta. He left immediately, going down the stairs swiftly. Why did the singer seem familiar?

He remembered as soon as he stepped into his brougham. This was Amodini. The same Amodini who had returned from the doorstep of death from cholera.

Dwarikanath raced upstairs again. The singer was back to the refrain. He pushed the door open and entered without seeking permission. The singing stopped.

‘You are Amodini…’

The singer’s eyes held a combination of astonishment and annoyance.

‘No, I am my own person, I am now Saras…’

Dwarika interrupted her. ‘No, you are Amodini, you are…’

He kept calling the name. And as he did, his large eyes brimmed over with tears.