It’s a tiny tea-shop, a mud-walled structure in the middle of nowhere. The hand-written sign on plain paper pinned to the front, reads:

Akshara Arts & Sports

Library

Iruppukallakudi

Edamalakudi

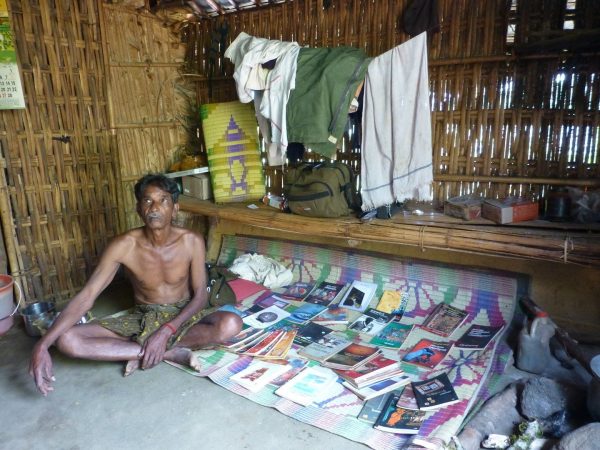

P. V. Chinnathambi runs a lending library in the midst of the Idduki hills of Kerala

Image courtesy P. Sainath/ People’s Archive of Rural India

A library? Here in the forests and wilderness of Idukki district? This is a low literacy spot in Kerala, India’s most literate state. There are just 25 families in this hamlet of the state’s first elected tribal village council. Anyone else wanting to borrow a book from here would have to trek a long way through dense forest. Would they, really?

“Well, yes,” says P.V. Chinnathambi, 73, tea vendor, sports club organiser and librarian. “They do.” His little shop — selling tea, ‘mixture’, biscuits, matches and other provisions – sits at the hilly crossroads of Edamalakudi. This is Kerala’s remotest panchayat, where just one Adivasi group, the Muthavans, resides. Getting there had meant an 18-kilometre walk from Pettimudi near Munnar. Reaching Chinnathambi’s tea-shop library meant even more walking. His wife is away on work when we stumble across his home. They too, are Muthavans.

“Chinnathambi,” I ask, puzzled. “I’ve had the tea. I see the provisions. Where the heck is your library?” He flashes his striking smile and takes us inside the small structure. From a darkened corner, he retrieves two large jute bags — the kind that can carry 25 kilos of rice or more. In the bags are 160 books, his full inventory. These he lays out carefully on a mat, as he does every day during the library’s working hours.

Our band of eight wanderers browse the books in awe. Every one of them is a piece of literature, a classic, even the political works. No thrillers, bestsellers or chick lit. There is a Malayalam translation of the Tamil epic poem Silappathikaram. There are books by Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, M.T. Vasudevan Nair, Kamala Das. Also titles by M. Mukundan, Lalithambika Antharjanam and others. Alongside tracts of Mahatma Gandhi are famous radical polemics like Thoppil Basi’s You made me a Communist.

“But Chinnathambi, do people here really read such stuff?” we ask, now seated outside. The Muthavans, like most Adivasi groups, suffer greater deprivation and worse education drop-out rates than other Indians. In reply, he fishes out his library register. This is an impeccably kept record of books borrowed and returned. There may be only 25 families in this hamlet, but there were 37 books borrowed in 2013. That’s close to a fourth of the total stock of 160 – a decent lending ratio. The library has a one-time membership fee of Rs. 25 and a monthly charge of Rs.2. There is no separate payment for the book you borrow. The tea is free. Black and without sugar. “People come in tired from the hills.” Only the biscuits, ‘mixture’ and other items have to be paid for. Sometimes, a visitor might get a free, if spartan meal, free.

Chinnathambi keeps the library thriving, serving the reading and literary hunger of his impoverished clientele

Image courtesy P. Sainath/ People’s Archive of Rural India

The dates of lending and return, names of the borrowers, are all neatly entered in his register. Illango’s Silappathikaram has been taken more than once. Already, several more books had been borrowed this year. Quality literature flourishing here in the forests, devoured by a marginalised Adivasi group. This was sobering. Some of us, I guess, were reflecting on the sorry reading habits in our own urban environment.

Our group, with several members earning a living from writing, was in for a further deflation of the ego. Young Vishnu S., one of three journalism students from the Kerala Press Academy travelling with us, found a different kind of ‘book’ amongst the lot. A ruled notebook with several hand-written pages. It has no title yet, but this is Chinnathambi’s autobiography. He hasn’t got far with it, he says apologetically. But he’s working on it. “Come on, Chinnathambi. Read us something from it.” It wasn’t long, and it was incomplete, but a tale neatly told. It captures the first stirrings of his social and political consciousness. It starts, after all, with the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi when the author was around seven years old — and the impact that had on him.

Chinnathambi says he was inspired to return to Edamalakudi and set up his library by Murli ‘Mash’ (master or teacher). Murli ‘Mash’ is a legendary figure and teacher in these parts. He is an Adivasi himself, but from a different tribe. One which resides in Mankulam, outside of this panchayat. He has devoted much of his life to working with and for the Muthavans. “Mash set me in this direction,” says Chinnathambi, who lays no claim to doing anything special, though he is.

Edamalakudi, where this hamlet is just one amongst 28, has less than 2,500 people. That’s almost the entire Muthavan population in the world. Barely a hundred live in Iruppukallakudi. Edamalakudi, which covers over a hundred square kilometres of forest, is also the panchayat with the lowest number of voters in the state, barely 1,500. Our exit route from here has to be abandoned. Wild elephants have taken over the ‘short-cut’ to Valparai in Tamil Nadu that we had chosen.

Yet, here sits Chinnathambi, running what could be one of the loneliest libraries anywhere. And he keeps it active, serving the reading and literary hunger of his impoverished clientele. And also supplying them tea and ‘mixture’ and matches. An otherwise noisy group, we set off in some silence, touched and impressed by our encounter. Our eyes on the treacherous path in the long trek ahead. Our minds on P. V. Chinnathambi, librarian extraordinary.