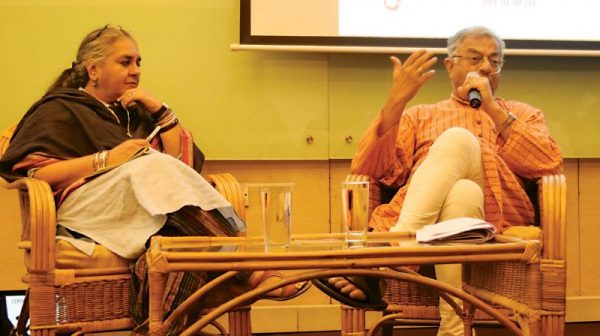

In part two of the two-part conversation between Arshia Sattar and Ananya Vajpeyi, they talk about the “dialogue between life and literature”, Sattar’s identity as a Muslim writer and translator in an India that is dominated politically by the Hindu Right, and more.

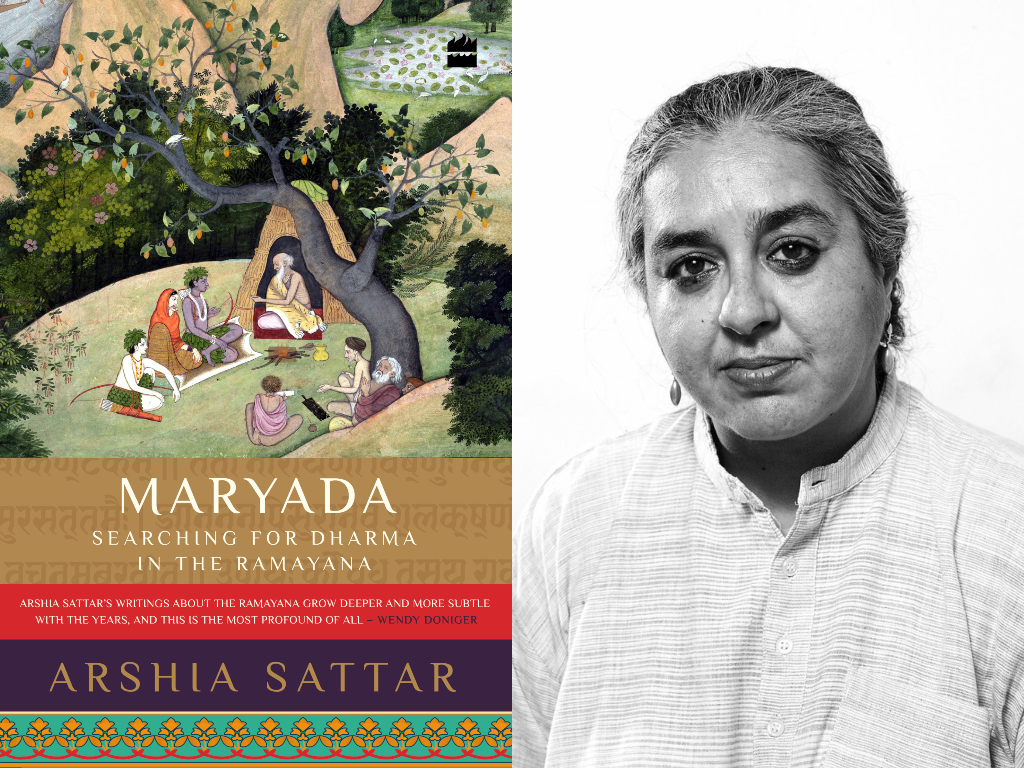

Arshia Sattar has written several books about Ramayana including Lost Loves: Exploring Rama’s Anguish and Uttara: The Book of Answers. Her latest book titled Maryada: Searching for Dharma in the Ramayana (HarperCollins) is set to release by the end of April this year.

Ananya Vajpeyi (AV): Your journey in philology and literature began decades ago, and you have devoted your life to the study and translation of the Sanskrit epics, especially the Ramayana. You were trained by some of the greatest modern scholars of Indic languages and civilisations, including A.K. Ramanujan and Wendy Doniger.

It must rankle you that today, in an India that is dominated politically by the Hindu Right, your scholarship is judged on the grounds of personal identity, be it religious, social, gender-based or regional. How do you respond to this? How do you deal with it, in your work and in your life? What are your strategies for preserving your intellectual space, your academic rigour, and your creative inspiration in an environment saturated with identity politics, prejudice, misogyny and bigotry?

Arshia Sattar (AS): Of course it rankles, hugely. At its least, it’s irritating and at its worst, it’s threatening. I don’t follow what people say about me, I’m not on Twitter, I don’t read any of the comments that people post when my articles are published digitally. I keep my privacy walls on Facebook very high. Occasionally, something slips by and it’s very disturbing — so, really, I don’t know and I don’t want to know the bad things people say about me. I have to keep that out of my head if I am to keep writing and working the way I do. I have good friends who alert me if some comment seems particularly aggressive and I am agitated for a few days. But then, it goes away.

As far as I know, the hostility to me has only been on the basis of my name, not my gender or my regional origins or biases. It’s always about me being a Muslim and not about me being a woman and never about where I come from. No one has ever asked me where I come from, I guess you never ask a Muslim that. A Muslim is othered enough as it is, who cares whether it’s a Muslim from the South or the East writing about a text that’s from the North — a Muslim is always an outsider unless they’re talking about their own religious and literary tradition.

In real life, in formerly polite company, the question about being Muslim is usually phrased as “how did you get interested in Ramayana?” and I play dumb and say, “the same way you did, I grew up with it,” which is actually true, I did grow up with Ramayana. Now, though, I’m more aggressive and I respond with “are you asking me that because I’m a Muslim?”

In my work, it’s very simple, I know how to do only one thing — write about Ramayana — and so I do it. What’s depressing is that over the last couple of years, I’ve stopped teaching and speak less and less in public. What used to be healthy and impassioned discussions can now easily become charges of sedition. And that is bound to affect my work — one’s best books are written through an engagement in conversation and opposing ideas.

Also Read | “The Ramayana is also a love story”

AV: You studied in Chicago, but in India you have lived mostly in Bombay (where you are from), in Pune (where you taught for some years) and Bangalore (where you settled down), is that correct? All these are cosmopolitan cities, where one may take certain freedoms, whether private or public, for granted. How have these places nurtured you, enabled your scholarship as an Indologist, and given you the room you need to do the work you do? If I may ask, which of them do you like living in the most, and why?

AS: I haven’t “settled down” in Bangalore, I live here now. And I think that has always been true — wherever I have lived, it has always been for the moment. Maybe because we lived all over India as a family and then with Sanjay Iyer, too, we tended to move rather than settle. I think of Bombay as my home, but that place doesn’t exist anymore, not even in name. Still, that city and those streets and that light and that air remain my most familiar and I love them dearly, if not best. I’ve always been a city person, both my parents’ families had been urban for two generations previously and so we have no roots, no ties to a mythical village or ancestral place. Besides, my parents come from different parts of the country and though they’re both Muslim and grew up and met in Bombay, they shared neither language nor clothes nor food.

I think if you are a metropolitan by birth, any and every city can be home and enable work and love and friends and community. Yes, cities are about freedom and I am profoundly grateful to have had freedom always, especially as a woman. What I may have lost in terms of cultural roots and a so-called mother language, I have gained as much by being entirely free to make myself into who I want to be. And that includes being a feminist, a teacher, a writer.

AV: In Bangalore, you must experience viscerally the loss of friends and mentors like D.R. Nagaraj, U.R. Ananthamurthy, Gauri Lankesh and Girish Karnad in recent years. This is in addition to a more intimate, more painful loss in your personal life. Did these relationships enhance and enrich your reading of the epics and of other Sanskrit classical literature? Did your literary interlocutors radically change the way in which you read, say, Rama or Sita or Hanuman? Could you give us examples from your experience, of the dialogue between life and literature?

AS: Girish is the only one of these who was continuously a friend and someone to whom I feel truly close. He cared about what I wrote and he was the first one to be interested in the root idea for Lost Loves — that made me feel that what I wanted to say was worth saying and would be of interest to others. No small thing since it came ten years after the Ramayana translation — ten years in which I had done many things but there was no engagement with Sanskrit. Also, it was my first book that was not a translation. So Girish’s interest meant a great deal.

Still, however, my first and most important interlocutor is Wendy. Sanjay and I talked a lot about Ramayana, most of my close friends have been subject to long and complex monologues about this and that in the text. The classroom has always been a space of creativity and indulgence — you can put your ideas out there and listen to them being spoken by yourself and by your students and you can reel them back in when they don’t work. I was given the most wonderful idea about Hanuman a few months ago by a student of Chinese ethnicity in Singapore at the UChicago Study Abroad program and it became an important heuristic device in the Hanuman chapter of my new book. Another non-Sanskrit, non-Indology friend also pushed me to think about Rama in ways that appeared in Lost Loves.

I think because I left formal academia 30 years ago and left my Chicago intellectual community so conclusively (this was before email and cheap phone calls), I have found interlocutors and inspiration anywhere and everywhere. And yes, I am enriched by the fact that these conversations are not academic or strictly scholarly. I think these have freed me to write for more general audiences.

AV: You have helped establish the Sangam House Residency, and are closely involved with writers, artists, and pedagogical endeavours of various kinds. You are also a translator, and you are deeply involved in film, theatre and the performing arts. How do you balance your solitary life as a scholar against your more publicly engaged work with peers and students across a range of institutions? Since you work outside the confines of formal academia, what are your views on the value of mentorship in the humanities?

AS: Maybe all the public involvement in arts and literary communities is precisely to compensate for the solitary life outside academia. If you stay with an academic institution, your intellectual and creative engagement is handed to you on a platter. If you work outside this milieu, you have to make it for yourself. For me, there’s nothing more terrifying than solipsism, when you have no reality check and live and work as if you are the entire universe.

As for supporting, nurturing and disseminating the perspectives that the humanities can provide, it’s probably the single most important thing that we can do. I’ve taught mainly in the Science and Liberal Arts programs with various “technical” or job driven academic institutions — film schools, design schools, development studies programs.Good that these schools see the need for the humanities — but these are always elective courses, they are never integrated into the main program, the grades and credits are treated differently, students are not required to engage as fully with a literature or a theatre class. We’re the side show, the circus that has come to town. There isn’t much hope for developing respect for the humanities and the critical thought processes and values it leads to, if this continues. And so, again, we have to work outside formal academia and I do that often, with weekend workshops on the epics in private spaces.

Nothing is better than literature to generate empathy and compassion. We can see that religion has completely failed in this regard, we must turn to stories of other people from other cultures who feel and act just like us — they love their children, they are sad when people die, they laugh when someone slips on a banana peel, and so on.