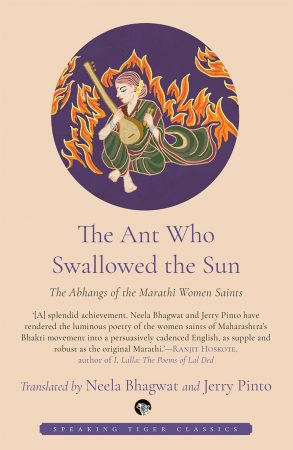

The Bhakti movement, which began around the 6th century, took seed in Maharashtra in the early 13th century in the form of the Warkari movement. Translated by Neela Bhagwat and Jerry Pinto, The Ant Who Swallowed the Sun is a collection of translations of abhangs by ten prominent and lesser-known Marathi women-saints who belonged to this movement. Their abhangs are not just expressions of devotion but offer a scathing criticism of patriarchy and caste hierarchies.

The following is an excerpt from the introduction to the book.

From Muktabai the brahmin woman-saint to Chokhamela the outcaste saint brings us into the same house as Soyarabai. She was Chokhamela’s wife, another saint-poet pair, who flourished spiritually at least in the ecosystem that Dnyaneshwar seems to have nurtured. Her voice, her personality, her poetics are distinctive. At one level, she was witness to the suffering inflicted upon her husband by the caste Hindus who resented his growing fame, and the popularity of his compositions. Perhaps there was also the fear among the brahmins of the basic message of Bhakti: that you need no intermediary between yourself and God; that anyone, however humble, could attain salvation and freedom from the cycle of birth and death; that you didn’t even need the scriptures or Sanskrit. All you needed was that holy name and the faith to hold on to it and make your way across the raging torrent.

At another level, Soyarabai stands witness, she says, to how Chokhamela’s faith saved him.

Pandhariche brahmane Chokhyahisi chhaleele

Tyaalagi kele naval deva.

Sakal samudava Chokhiyache ghari

Riddhi-Siddhi dwaari tishtataati.

Rangmala sade, gudiya torne

Anand kirtan Vaishnavache

Asankhya Brahman baislya pangati

Vimaani paahaati suravara

To sukha sohla Diwali-Dasara

Vovaali Soyara Chokhyaachi.

The brahmins of Pandharpur tormented Chokhamela

But Vitthala did not let His devotee down.

Countless brahmins sat down to eat and found

Chokha’s house was decorated up and down.

Riddhi and Siddhi stood at the doors

Where garlands hung and torans unfurled

Hymns were sung in Vishnu’s praise

The gods look down upon this marvel

It was like Diwali and Dasara at once

And Soyara offered an aarti to Chokha.

There is much joy in this moment but there is an equal amount of joy in her expression of her love for Vitthala.

Shinalya bhaaglyaancha toochi visaava

Dhaave tu Keshava maaybaapa.

For those tormented by life, You are the only refuge

Come quickly, my lord Keshava.

Soyara has an acute awareness of the injustice she faces but she also has a philosophical ability to confront the contradictions of the caste system. She expresses this in her abhangs where she comes across as an independent woman with a keen sense of the ridiculous. Take the abhanga, ‘Kiti he marti, kiti he radti’, on page 70-71 as an example and you will see what I mean.

There is a modern quality to Soyara’s tonality, and it might be possible to see the roots of the ironic, the awareness of contradiction that marks modern poetry in her work. Chokhamela says of menstruation, which was seen as ritually impure:

Panchahi bhootaancha ekachi ekaachi vitaal

Avaghaachi mel jagi naande.

The five elements mingle in this pollution

Which is the source of creation in the world.

Compare this to ‘Dehasi vitaal mhanati sakal’ which is on page 80-81 and you can see the way in which the two voices chime and resonate with one another.

Chokhamela’s sister Nirmala is a spontaneous and outspoken woman. That is her strength. If Soyara calls herself ‘Mahaari Chokhyaachi’ (the Mahar Chokha’s wife), Nirmala announces herself as ‘Bahin Chokhyaachi’. But this does not prevent her from taking on the Godhead.

Chokhyasi sukha vishraanti didhli

Maajhi saanda keli disatase.

To Chokha You give all manner of happiness

What am I to You? A bull to be kept at arm’s length?

She does not stop there.

Toda phaasa yaacha maaybaapa

Nirmala mhane aata duujepan

Chokhiyaachi aana tumhi ase.

I have no taste for this life

Break these fetters from around me

Why are we not one?

I demand this union in Chokha’s name.

She believes so strongly in the power Chokha has over Vitthala that she feels she can use his name to bring Vitthala around. Then she offers her neck in an act of abject surrender.

Maandivari maan thevili sampoorna

Pudeel karanaa jaanoniya

Nirmala mhane taaraa athva maaraa

Tumche tumhi saaravozhe aataa

My neck I place upon Your knee

I know what will happen to me now

Nirmala says: Save me or kill me

Unburden Yourself now.

We live in a world that prizes the individual and the freedom of the individual. How are we to understand this surrender? As a feminist, how do I understand this surrender to a male force? (Then the next question: Is it a male force? But that is a debate for another time.) For me, Nirmala’s challenge is the challenge of accepting consequences. You must choose the path you tread and you must accept the consequences of that choice.

*

Kanhopatra, was a 14th-century saint, and a sex-worker as well. She was the object of male lust and her devotion to Vitthala is a protest against the patriarchal world which enslaved her body but could not touch her spirit. Her intensity is amazing and touching. Perhaps it was because of this background that so little is left of her work.

The 17th-century Bahinabai was also able to liberate herself and her husband from the clutches of patriarchy through her faith. Her songs are a narrative of her life, telling of simple joys and sorrows. Her husband does not come across as a very nice man. What kind of man would kill the calf to which he can see his wife is very attached? Bahinabai watches all this and she mourns the loss of these attachments but she stays the course. It might be argued that she is another woman who chooses to suffer; but she must have had no alternative. In the dark world of her troubled marriage, Vitthala was a light leading her forward. And eventually, she did get her happy ending; her husband too was saved.

Kanhopatra considers Vitthala her husband. There is a parallel here with Sant Meerabai of the 15th century. Meerabai tells us of the strong love she had for Krishna and the frustrations of living an earthly life and trying to contend with an earthly husband. Eventually she liberates herself from the constraints of the caste system and takes the cobbler Rohidas as her guru. She leaves the palace and the royal family; she joins the legion of Krishna bhakts who include men and women of all walks of life and all strata of society. Kanhopatra curses her profession as lowly; she wants to be pure and acceptable to Vitthala. Eventually, she too, like Sant Meerabai, attains her goal.