This essay is from Ismat Chughtai’s collection of essays that elucidate the painful transition of the Indian subcontinent from colonial rule to independence. Titled “Communal Violence and Literature”, it talks about the role of a writer in times of political turmoil and communalism, while making a case for ‘art for life’s sake’. An irreplaceable part of the Progressive Writers’ Association, along with other litterateurs like Saadat Hasan Manto and Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Chughtai is considered to have trailed a new blaze in the history of Urdu literature by bringing in themes that were untouched before, like female sexuality.

Chughtai’s “Communal Violence and Literature” holds extreme significance in contemporary India and its extremely communal atmosphere. We publish here the entire text of the essay, as a reminder that, in fact, we have not come a very long way from the time this was written.

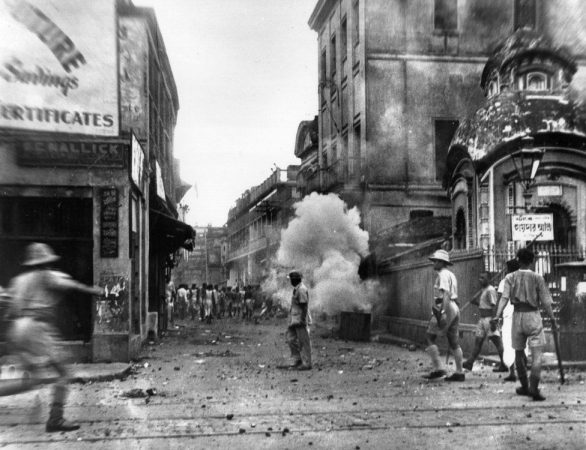

The flood of communal violence came and went with all its evils, but it left a pile of living, dead, and gasping corpses in its wake. It wasn’t only that the country was split in two—bodies and minds were also divided. Moral beliefs were tossed aside and humanity was in shreds. Government officers and clerks along with their chairs, pens and inkpots, were distributed like the spoils of war. And whatever remained after this division was laid to waste by the benevolent hands of communal violence. Those whose bodies were whole had hearts that were splintered. Families were torn apart. One brother was allotted to Hindustan, the other to Pakistan; the mother was in Hindustan, her offspring were in Pakistan; the husband was in Hindustan, his wife was in Pakistan. The bonds of human relationship were in tatters, and in the end many souls remained behind in Hindustan while their bodies set off for Pakistan.

Communal violence and freedom became so muddled that it was difficult to distinguish between the two. After that, anyone who obtained a measure of freedom discovered violence came alongside. The storm struck without any warning, so people couldn’t even gather their belongings. When things cooled down a bit people collected themselves and had a chance to observe what was going on around them.

With every aspect of life disrupted by this earth-shaking event, how could poets and writers possibly sit by without saying a word? How could literature, which has close ties with life, avoid getting its shirtfront wet when life was drenched in blood? Forgetting the struggles of love and separation, people concentrated on saving their skin and bones. Like the followers of Satan, they went beyond the conventional styles of romance. Caravans of refugees put Farhad’s wandering in the desert to shame, and even the ghazal, regarded as the beloved of feudal aristocracy, forgot its play and, escaping from the alley of the adored one, began drifting among the burning bazaars, pillaged houses, and heaps of crushed humanity. There was no other recourse. After all, gham-e janaan had to be transformed one day into gham-e dauraan.

As soon as the writers and poets had a moment to breathe, they turned towards their objective. A variety of viewpoints and sentiments, some progressive, some reactionary, and still others that were neither of these but some mysterious entity in the middle, could be observed. Some writers, armed with plaster and mortar, threw themselves headlong into laying this mortar and whitewashing.

Walls that had crumbled were raised again, leaking roofs were repaired, demolished halls were given a new lease of life—the individuals doing this were motivated by a creative literary purpose. Foremost among them were writers born under the canopy of foreign rule who had long since become disillusioned with it and, now disgruntled, were looking forward to its departure from their country. The moment they saw the white-skinned pirates leaving Hindustan they danced about, clapping their hands like little children. They were so intoxicated with the notion of freedom that they felt no shame or embarrassment in jumping about excitedly on the streets. And anyway, who had time to be embarrassed? The Union Jack was slipping while the tiranga was being raised high. The nationalists allowed their thoughts to soar. Just as the four-anna wallahs in cinema halls whistle loudly and express their delight at the appearance of the hero mounted on his steed, so these intoxicated lovers of freedom danced and celebrated in the streets when they saw the heroic tiranga soaring in the sky.

“Dance joyfully, sing songs of mirth,” sang Prem Dhawan.

“Advance, because the time is for singing and celebration; arise, it is the arrival of spring,” roared Josh Sahib.

“The sun has come out with such pride today/Himalaya’s lofty peaks are glittering,” Jazbi proclaimed emotionally. He said excitedly:

Sing, o Ganga,

Move lightly, breeze of the garden.

Shimmer joyously, Himal

For the mountains and valleys are dancing.

And statues of Ajanta,

Sing on, sing on!

“Free, free, Hindustan is free,” said Jaan Nisar Akhtar rapturously. “My Delhi, my beloved Delhi.”

No longer the whore of tyrannical emperors, no longer the slave-girl of feudal lords, the market of the foreign capitalists.

But the centre of our hopes, the realization of our dreams. The image of our desires.

“I see a radiance on your face today…” declared Jafri.

But 15th August came and went, leaving behind embarrassed, whimpering and teary-eyed masses. The hearts that had been singing were hushed, the dancing feet were stilled. Those who did continue to dance had no idea what beat or melody they were dancing to. Disappointed hearts began to understand. Suddenly it became clear that they had been handed a tinned moon with plating so brittle that it didn’t last for more than two days. What they had welcomed as the morn of truth was just a firecracker whose temporary brightness had seduced naive hearts into singing for joy. The ones who departed went so adroitly that they took only the body and left the soul behind. What a tragedy that they divided freedom into two parts and handed them to the people, saying “Pakistan is for the Pakistanis and Hindustan is for the Hindustanis.” But when the accounts were settled it became clear that the bigwigs of Hindustan and Pakistan got everything, while those who had been empty-handed before Partition remained empty-handed. As the saying goes, a blind man distributing rewaris kept doling them out to his kinsmen. So Josh Sahib spoke angrily:

This measuring, this cutting, this wanton devastation.

The drowning of the swimmers, the helplessness of the fighters,

What shall we call autumn, if this is spring?

And Sardar Jafri gnashed his teeth and proclaimed furiously:

From whose forehead has the ink of slavery been wiped off?

The anguish of bondage torments my heart still

There is the same sadness on the face of Mother India,

Daggers are free to plunge into bosoms,

Death is free to drift upon corpses.

And Majaz said quietly:

All these whose hands are dripping with blood,

They were the very messiahs, the Khizrs.

From across the border Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi informed us that all was not well there, either:

Pieces of bread weighed against snippets of flesh

In shops decorated with honour,

After the appetite is satiated

The taste of blood dances upon the tongue.

And Majrooh said irately:

Now it is they who had once endured the pain of captivity who bequeath the pain of captivity. And Akhtar said tearfully:

I was happy that my country had been freed.

But he soon found out that

The flower lost its colour the moment it was touched,

The garland had yet to be braided when it came undone

The goblet hadn’t touched the lips when it was shattered,

It’s not my dreams that have been looted and pillaged, it is me.

In other words, there were protests everywhere. But before a demand for an explanation could gain strength, communal riots burst upon the scene with a blast. Clearly, dealing with the violence became more important than the clamour for rights. Most of the Progressive writers in Hindustan and Pakistan turned their attention to this issue and, helped by other progressive elements, began their work in earnest. The force of the pen thwarted the attacks of the knife and dagger. Although the reactionaries sided with the dagger and knife, it was the progressive elements that finally won. This was a time when the value of life was equivalent to a fistful of sand. The helpless victims had been unleashed in the field; every demand was met by adding fuel to the blaze of communal violence. The organizers were standing with their backs turned; the reformers of the nation were dozing somewhere out of sight. This was the moment when writers provided ammunition in the form of plays, sketches, stories and poems, scattering them everywhere. Ahmad Abbas scribbled his play, Main Kaun Hun? (Who Am I?) in ninety minutes, rehearsed it, and that same evening arranged performances in several parts of the city. Abbas did not have time to consider the fact that his haste might compromise his art, that it might belittle the power of his pen, that a writer’s greatness might be diminished. If he had thought about all this he might have turned Main Kaun Hun? into great art, but then it couldn’t have doused the fire blazing at this time. This burning world needs dousing more than it needs works of art.

Around this time Krishan Chander set up a veritable fortification and sent an army of afsaanas, stories and sketches into the field. The speed with which the riots spread was m atched by the speed with which Krishan’s afsaanas were circulated through magazines in both Hindustan and Pakistan. Intentionally or unintentionally, this bombardment occurred in such a way that no other example can be found anywhere in the world where one writer produced so much material in such a short space of time, and his prescription truly proved beneficial. Whatever Krishan Chander wrote, he wrote dispassionately, wittingly and, perhaps, under pressure. It may not have come naturally to him and may appear affected, but he wrote because he felt he had to, because the situation called for it.

This was the time when both factions were already sparring with each other. A count hadn’t been done yet to determine which side had eliminated more adversaries. If the Muslims had taken out a procession of two thousand naked women, the Hindus had taken one out with four thousand. The Muslims six thousand. The Hindus eight thousand. Eight thousand, sixteen thousand, thirty-two thousand, one hundred thousand. If there had been someone clever among them, he would have done a count and then announced which party’s stalwarts had emerged victorious. But the fact is, every victor looked vanquished, everyone’s head was lowered in remorse.

Whatever Krishan Chander, Ahmad Abbas, Sardar Jafri, Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi, Upendar Nath Ashk, Sahir Ludhianvi, Hajira Masroor and others of this family have written under the circumstances has been denied its place as literature by Aziz Ahmed, Hasan Askari and M. Aslam. They claim that these [Progressive] writers have weighed everything on a scale and given each savage an equal share; they think that in actuality only Hindus and Sikhs committed atrocities. I don’t know on what grounds they make this claim. Perhaps they have been supplied their figures by the brutes themselves, because anyone with any sense at all knows that both factions have committed atrocities and each side has attempted to outdo the other. In their opinion only a one-sided picture can clearly portray the events that took place. For example, they think Krishan Chander should only have written about what he saw with his own eyes. Just what would have happened had he done so? At the time Krishan Chander wrote his afsaanas, his house had been turned into a camp for refugees. Seeing the terrible condition of those who had fled from western Punjab, observing the effects of their mental and physical abuse, who knows what anger might have welled up in Krishan’s heart against the Muslims? Who knows what blinding curtain might not have covered his eyes that otherwise only discerned the truth as he sat among his near and dear ones? But what emotion and what strength made him throw off that blindfold and look beyond? How many times, afraid that he was becoming biased, must he have had to escape from his environment so that, away from the searing sighs of these sorrowful victims, he could draw the other side of the picture, using only his creative vision? Searching carefully and diligently, he selected and produced images that would have the same weight on the scales when they were exhibited. And during this time, anyone who loved his country would have done just that. On one side of the scale he put eyewitness accounts and on the other, pictures called forth from his imagination. If it had been anyone else he would have cheated. Or, like M. Aslam, he would have taken only one side of the scale into account. Or, as Askari Sahib suggests, he may not have called a tyrant a tyrant, nor condemned tyranny, and he may not have made an effort to combat evil. He would have written a few silly jokes and waited for that innate goodness (that supposedly accompanies baseness in every individual) to surface, and, labeling it an immortal literary creation, he would then have expected appreciation and approval. In my opinion, even if Krishan Chander throttled literature, trampled on the refined elements of art and created phony writing, he certainly did not remain unaware of his duty. He engaged in propaganda and became a rectifier of wrong. At a time when we needed a leader more urgently than we needed an artist, he did what was necessary, what was proper. In the eyes of Hasan Askari, Krishan might be a reforming idiot, perhaps because Askari himself was seduced by just such a reformer’s role. But we have got nothing to do with Hasan Askari’s values. We have immutable values before us. We will keep our sights on them.

Despite all this, whatever Krishan Chander and others wrote about the communal violence is not at all inferior by literary standards. The style, plot and imaginative quality of Hum Vahshi Hain (We Are Savages) are superior to all of Krishan Chander’s earlier collections. The passion, the tenderness which wasn’t apparent in Yahaan ke Nazaare (The Views Here) nor in Shikast (Defeat), and which, in fact, can be seen in no other work except An Daata (Master) are present here. The recent fiery passion that has become a part of Krishan’s work is due in great part to the fact that now there is a special commitment in his work, a purpose, a resolve and its subsequent realization. And this is what elevates his writing to such heights.

The second type of people are those who beat their chests and lament for their respective communities, thus encouraging and extolling the forces of factionalism. Toadies of feudalism and capitalism, they are opportunists and enemies of the people. They spend every last ounce of their energy to protect the spoils of war that fell into their hands when the country was divided. They believe that the common people are out to forcibly snatch their loot, so they are trying to distract them by staging communal riots. They have been trained by the British and are their true heirs. In the past, whenever the Hindustanis expressed a desire to be free, these people immediately instigated riots. Now that the British have left (physically), these new rulers fear that this freedom-only-in-name will be seen for what it is. There is no other recourse for them but to hide behind religious differences and split the country in two. Besides, as the saying goes, we are flogging a dead horse. In other words, first the country is divided and then to make matters worse, there are communal riots. Continual dissension must be created to keep this division alive.

Keeping these very considerations in mind, M. Aslam wrote his Raqs-e Iblis (The Dance of Satan). Except for its reactionary sentiments, this novel has nothing to offer. It is neither interesting nor stimulating. The narrative style is puerile and flat. Because not a single episode, from start to finish, has been presented in a realistic, effective manner, there is little or no verisimilitude in the entire novel. The characters are stereotyped and crudely delineated. Two rather silly male characters engage in a conversation in stilted, broken language about this rumour and that, speaking so inanely that after a while one feels no desire to continue reading. The novel’s hero, Mehbub Elahi, has fled from East Punjab after losing everything, including his bride who was kidnapped the day after he married her. Just before he leaves he buries his mother with his own hands. In spite of all that he has suffered he carries on quite pleasantly about clean beds, baaqarkhaanis and sugar. But in the end, when his kidnapped wife, assaulting everyone along the way like the heroine from The Stunt Queen, returns to him completely unharmed and still a virgin, a tirade of anger and invectives is let loose against seven generations of the other group.

If someone with a more forceful pen than M. Aslam had written a novel from this point of view, it would indeed have been a dangerous work. However, as things stand, there’s no such danger. But, let’s forget the novel. What is more important is the Preface, the product of Hasan Askari’s pen. After reading just the first page it is clear what the narrative contains and how crudely it is presented. With the exception of M. Aslam, Hasan Askari, and perhaps Aziz Ahmed, no other critic in Pakistan, Progressive or otherwise, has praised Raqs-e Iblis. Apparently the reactionary front is not very strong in either Hindustan or Pakistan.

As a counterpoint to M. Aslam’s thrust, Ramanand Sagar wrote a novel, Aur Insaan Mar Gaya (And Humanity Died). I read both these novels at about the same time. Technique aside, the two novels are very similar in terms of subject matter and point of view. Although Ramanand Sagar was not a Progressive writer, he was not a reactionary either. Placing him in the same category as M. Aslam I feel as if I too am standing alongside them. This is because I have always regarded Ramanand as a member of my own family and it pains me to see him sharing M. Aslam’s views.

In Raqs-e Iblis M. Aslam has written about the atrocities committed by the Hindus and Sikhs against the Muslims.

In Aur Insaan Mar Gaya Ramanand Sagar has written about the atrocities committed by the Muslims against Hindus and Sikhs.

M. Aslam has a Sikh who risks his own life in order to save Muslims.

Ramanand Sagar also manages to find a Muslim maulana to perform a similar service for him.

M. Aslam’s heroine is kidnapped by Sikhs and Ramanand’s is seized by Muslims.

At this point, however, M. Aslam offers greater evidence of his progressivism. When his heroine, Khursheed, returns to Pakistan, her husband accepts her without asking any questions. On the other hand, when Ramanand Sagar’s heroine returns, ravaged and ruined, she is so disheartened by the stupid hero’s indifference that she commits suicide. Ramanand Sagar seems reluctant to support a fallen woman.

In M. Aslam’s narrative the ending is optimistic; the future, as he sees it, is bright. In Ramanand’s story there is only despair, a hopelessness that seems to reach new heights of silliness.

M. Aslam’s characters, those that are left intact, start a new life. Ramanand’s commit moral and physical suicide, they go mad and behave savagely, hoping thus to attract the reader’s sympathy.

The preface to Aur Insaan Mar Gaya has been written by Ahmad Abbas, who has done everything possible to outdo Hasan Askari in his reactionism. For instance, while Askari Sahib remarks that Raqs-e Iblis is truly creative and constructive literature, Ahmad Abbas says he saw a lone star in the darkness and it was Ramanand Sagar. And the fact that he (Ramanand) thinks that humanity is dead is the very proof that humanity is indeed not dead. I don’t know what kind of logic this is. Maybe Ramanand Sagar and Ahmad Abbas alone have grasped that “pessimism” is in reality “optimism”. When Ramanand Sagar killed every human being and every animal in his novel, Abbas was convinced that “death” is, in reality, “life” and everything else is just plain nonsense.

Askari Sahib says that the people actually responsible for communal violence are the Sikhs and the Hindus; the poor Muslims only committed atrocities now and then to defend themselves. Ahmad Abbas feels that ordinary people started the riots, that they are solely responsible for all the violence and that they slit each other’s throats just for the fun of it. In saying this he ignores completely the effect of years and years of foreign rule and colonialism. He probably believes that it was these very people who demanded Pakistan and got it.

Such Hindustanis and Pakistanis wish to shield with their writing that particular class which, driven by a desire for personal gain, in fact perpetrated and was the real progenitor of the Partition and its ensuing violence. This class is not particular to any one country, but rather, except for a few nations, is found everywhere on earth. It commits such acts and looks for similar justifications.

However, we shouldn’t be fearful nor should we lose hope. Such writing has rarely been taken seriously or applauded by the general public. It’s possible that they may be swayed momentarily, but these tabors and kettledrums cannot keep the public distracted for long.

However, there are others who form links between constructive and destructive literature in this chain. Among them is the one represented in Mumtaz Shirin’s short story “Bharat Mata.” The gist of the story is that first Mother India is cut up into many parts—which is all right—and she feels some pain; then she is convinced that whatever has happened is for the best. By personifying Hindustan as a mother, Mumtaz Shirin has flung the word “mother” face down into slime. Is there a mother anywhere whose child is torn in two and she claps her hands joyfully, exclaiming, “Ahha, ahha! Now there are two, and both are my sons.” This analogy is crude and frightening. I respectfully submit that if the Honoured Lady is a mother herself, then it is very odd indeed that she should present such a ridiculous view regarding children. And if she’s not burdened with being a mother herself, she’s still a woman and a woman can never tolerate a mockery of the mother-child relationship nor deliberately attack it. Even without this analogy, her proposition that if something is split in two it will thrive better sounds odd. Does this mean that if left whole it will stop growing? The Respected Lady is harbouring a grave misconception. It’s possible that division will momentarily staunch the flow of the rapids, but if by some chance the two parts come together at some point, no barrier or forethought will be able to stem the ensuing deluge. What will happen if the courage and resolve weakened by the division were restored? She didn’t think this through. But no, I’m mistaken. She has indeed thought it through carefully and is saying all this as part of a calculated programme. All the same, these tactics will prove ineffective in the end. Meanwhile her kind of literature is even more lethal than literature generally regarded as destructive. For the latter merely aims at causing disruption, while the former conspires to dig out the very roots of the tree and plant a new seed. Should such a seed ever take root, it will crush willpower by holding out false hopes and hollow promises.

I’m at a loss about what to do with [Saadat Hasan] Manto’s Siyah Haashiye (Black Margins): should I catalogue it as a work of literature or should I find an entirely new classification for it? Manto is very fond of things that create an uproar and awaken with a start even those who are fast asleep. He thinks that if a man smeared with mud walks into a group of people all dressed in shining white, this will shock them; or if someone bursts into raucous laughter in a gathering of people weeping and wailing, this will make them look at him in wonder. Well, that will impress everyone, he will be famous.

Usually this tactic pays off, and Manto has managed to receive a lot of applause, but the arrow has missed its mark this time. Surely Siyah Haashiye is neither a masterpiece nor a timeless marvel, but it’s not garbage either. There are several pieces in this collection that move us to tears. But in his Preface Muhammad Hasan Askari has done the collection a great injustice. He has misrepresented the contents by cloaking them in a garb suited to his own fancy. What does he mean by saying that Manto does not regard tyranny as tyranny? Does he think that he regards the tyrant as the beloved? I don’t think Manto ever says such a thing. Whatever else he might do, Manto would never claim that evil people are creations of their own minds or that God has made them this way, or that social and political forces play no part in making them what they are. Askari Sahib believes that tyrants should not be opposed because they won’t change. Is he suggesting that if someone hits you over the head with a club you should say, “Well, brother, let me have a few more blows?” Askari Sahib may possess such lofty sentiments, but no sane person can tolerate this sort of thing, certainly not Manto. Manto will use conciliatory tactics only so far; if a person persists in his aggression, he will resort to force. I don’t know what pleasure Askari Sahib derives from mutilating Manto’s point of view, but this ill serves Manto. Manto may be many things, but he cannot be bigoted, and won’t be forced by anyone to become so; he won’t approve of violence. A man whose heart melts at the plight of the most despicable whore scorned by the whole world, who can look into the heart of a human being as debased as a pimp, whose sensitive nose doesn’t care for fragrance simply because it is characterized by affectation, sham and deception—Manto is not the sort of person who can fail to be affected by the sight of corpses. He is also not afraid of calling a tyrant a tyrant. Why would he hesitate to halt violence? We have been deceived. An attempt has been made to blur our vision. Manto’s writing has been used as a tool to carry out some hidden agenda. His style is sometimes abstruse, he’s used to presenting his ideas in a roundabout way, but I know that Manto was not laughing when he wrote Siyah Haashiye, nor did he write these tales to make people laugh. No matter how he is hoodwinked, Manto will never write reactionary literature.

This then is a glimpse into the kind of writing that was produced in the throes of the violence following Partition. What we have to see now is how much of it is going to survive and how much will be useful only as wrapping paper in an apothecary’s shop. It is a mistake to say that this is merely riot-specific literature, and that as the violence dissipates, so will its importance and popularity. In one way or another, all literature is time-specific. Whatever Maulana Hali wrote during another tumultuous period of Indian history has survived as great literature. Likewise Gorki’s writings will never be diminished in stature, although the revolution during which he wrote is long since over in his country. Every word that was written about the repugnant traditions of bondage is still highly valued today. And though the Spanish revolution is over, the greatness of For Whom the Bell Tolls endures.

So those who want to devalue the literature on communal violence by characterizing it as the product of a specific situation, and hence merely short-lived propaganda, are mostly individuals who couldn’t produce anything of value themselves, or perhaps found it at odds with their own purpose. They are creating an impression that this literature is not significant in order to clear the field for themselves. The life and death of literature depend on its content as well as the talent of writers. It is total narrow-mindedness to say such literature is time-bound.

I don’t mean to imply that every crisis will give rise to enduring works of literature. For example, a sehra written on the occasion of the wedding of a nawab sahib’s darling dog, or a marsiya drafted by a school headmaster on a kalaktar sahib’s transfer to another town will never be immortalised. To create great literature one needs a sensitive heart and specific goals, or, as the poet says:

There is no timeless subject in the world, Majrooh

Whatever I touched became eternal.