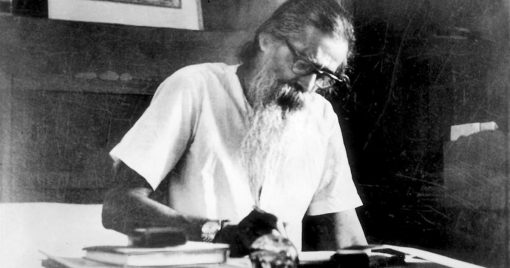

The 114th birth anniversary of Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar went unnoticed. Barring a stray article by a second-rung leader of the saffron party in a national daily, none from the top hierarchy deemed it even necessary to remember the second chief of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) who followed the organisation’s founder, KB Hedgewar.

Interestingly, while Twitter-savvy Prime Minister Narendra Modi found time to tweet about his litti chokha conquest at Hunar Haat in Delhi, there was not a single line about Golwalkar on his timeline that day. It appeared a bit strange because in his book titled ‘Jyotipunj’ on the “greatest social workers” who “burnt their lives to glow the Motherland”, Modi had devoted forty pages to Golwalkar. “The life of Golwalkar Guruji is a fine example of dedication. Guruji, possessed all those qualities which are expected of an individual who lives for his goal—patience, determination, perseverance,” he wrote.

Was Modi’s or his senior colleagues’ silence inadvertent, or deliberate?

It is rather difficult to believe that they collectively failed to remember the longest-serving (1940-1973) RSS supremo inadvertently.

How can they suddenly forget a man personally chosen by Dr Hedgewar, its founder and first supremo, to lead the organisation and be the “prime architect” of the organisation? External observers and RSS insiders agree that Golwalkar can be considered the key figure who provided a theoretical background to the Hindutva project and sowed the seeds of its vast organisational network. As of today, the plethora of anushangik (affiliated) organisations which owe allegiance to Hindutva would run into the hundreds, each catering to a different section of society.

Merely a decade and a half ago, the Sangh Parivar and all its affiliated organisations had celebrated Golwalkar’s birth anniversary in a big way with a focus on “'social harmony” (samajik samrasta) as the central theme. A massive campaign was launched where “Hindu rallies” were organised at the block level all over the country. Seminars, symposia and lectures took place “to propagate the ideas and vision of Shri Guruji,” the RSS-mouthpiece Organiser had said.

It was a phase when the “glorification of Golwalkar” made him “stand a little above the human level,” according to Prof GP Deshpande, who wrote as much in an article published in the EPW at the time. Deshpande was referring to the addition of “Shri” to Golwalkar’s name, a title which made him appear “nearly sacred, an avatar of sorts”.

“Within the Maharashtrian context this has an additional meaning or signification. Mystic gurus are often referred to as ‘shreeguruji’. You can see thus that there has been rather subtle glorification of Golwalkar, the new appellation making him stand a little above the human level.”

Perhaps an indication of this slow ‘invisibilisation’ of Shree Guruji could be seen in RSS Supremo Mohan Bhagwat's three-day lecture series titled “Future of India” held in Delhi in 2018. It was projected as a first of its kind event—an outreach programme—to explain the “Sangh’s perspective on different issues of concern” and “clear misconceptions about its ideology and working”.

Back then, a correspondent with a leading English daily even counted how Hedgewar got the maximum number of mentions (45) during the presentations whereas Golwalkar was mentioned only once over the first two days. Interestingly, in his lecture, Bhagwat “invoked 32 different personalities as many as 102 times in the first two days of his lectures to show how the Sangh incorporates the best of diverse sources.” The RSS supremo even “referred to political figures like Mahatma Gandhi, BR Ambedkar, Motilal Nehru, Jawaharlal Nehru, Rabindranath Tagore, Subhash Chandra Bose, Veer Savarkar, MN Roy, AMU founder Sir Syed Ahmed Khan and even little known Sangh figures along with Buddha, Zarathustra, Ramakrishna Paramhans, Dayanand Saraswati, Vivekananda, Guru Nanak and Shivaji.”

Golwalkar, however, remained absent, making it obvious that it was not just Bhagwat, but all the leading lights of the Parivar who had second thoughts about invoking his name in public. This ended on the third day of the event, during the question-answer session, when it was claimed that the RSS wanted to present a sanitised version of Golwalkar’s controversial book, Bunch of Thoughts, which talks of Muslims, Christians and Communists as ‘internal threats’, thus vindicating their collective discomfort with his name.

The chapter on "Internal Threats", which has three subsections titled Muslims, Christians and Communists, begins like this:

“It has been the tragic lesson of the history of many a country in the world that the hostile elements within the country pose a far greater menace to national security that aggressors from outside. Unfortunately, this first lesson of national security has been the one thing which has been consistently ignored in our country ever since the British left this land (sic).”

The book has also made equally controversial statements on the Indian Constitution as well as on affirmative action and denigrates the independence struggle and its heroic participants. Bhagwat knew very well that for a new-look RSS, anti-human solutions offered by Golwalkar would prove costly.

The explanation offered by Bhagwat to bring out a new edition of the book was not very convincing: As far as Bunch of Thoughts goes, every statement carries a context of time and circumstance… his enduring thoughts are in a popular edition in which we have removed all remarks that have a temporary context and retained those that will endure for ages. You won’t find the (‘Muslim is an enemy’) remark there.

According to an analyst, it is similar to saying that a sanitised version of Hitler’s Mein Kampf, where direct references to targeting Jews could be removed, is possible, to present a more palatable and lovable Hitler.

Thus, it is not difficult to comprehend why the Sangh wanted to distance itself from Golwalkar in public.

A cursory glance at the trajectory of his life makes it clearer.

Remember, Golwalkar’s life spanned a period in world history which was unique in many ways. It was a period when Nazism and Fascism were ready to swamp Western Europe, a period when national liberation struggles in many of the third-world countries were nearing culmination. A time when great experiments of Socialist construction undertaken in Soviet Russia coupled with the rising tide of communist-led militant movements, were proving to be the era’s defining characteristics.

Retrospectively, one can say that it was a juncture in world history when the old world of feudalism and colonialism were crumbling and a new world was emerging. It would not be incorrect to say that due to his peculiar Weltanschauung, which yearned for building a Hindu Rashtra based on the ‘glorious traditions of Hinduism’, and which looked towards Muslims as a bigger adversary vis-a-vis British colonialism and which sought inspiration from the experiments in ‘social engineering’ undertaken by Nazism-Fascism, he completely failed to keep pace with the march of history. In fact, due to his intransigence, he not only kept himself personally aloof from the surging anti-colonial struggle, but also did not chalk out any positive programme for his organisation to participate in it.

The first of Golwalkar’s theoretical contributions for Hindutva’s cause appeared as a pamphlet titled We or Our Nationhood Defined (1938). It was so straightforward in its appreciation for the ‘ethnic cleansing’ of Jews by Hitler and such an unashamed proponent of the submergence of ‘foreign races’ in the Hindu race that later-day RSS leaders tried their best to create the impression that the booklet was not written by Golwalkar but that it was a mere translation of Rashtra Meemansa by Babarao Savarkar.

It is a different matter that in his preface to We or Our Nationhood Defined, dated 22 March 1939, Golwalkar himself described Rashtra Meemansa as “one of my chief sources of inspiration and help”. The American scholar Jean A Curran, who did a full-length study on the RSS in the early fifties, wrote a book sympathetic to the Sangh titled Militant Hinduism in Indian Politics: A Study of the RSS (1951). In it, he confirmed that Golwalkar’s 77-page book was written in 1938 when he was appointed RSS General Secretary by Hedgewar, and called it the RSS’ “Bible”.

A third arena where Golwalkar proved to be much behind his times was his love for Manusmriti’s edicts. When leaders of newly-independent India were struggling to have a Constitution which was premised on the inviolability of individual rights with special provisions of positive discrimination for millions of Indians who had been denied any human rights quoting religious scriptures, it was Golwalkar again who espoused the same Manusmriti as independent India’s constitution. On 30 November 1949, the Organiser complained: “But in our constitution there is no mention of the unique constitutional developments in ancient Bharat. Manu’s laws were written long before Lycurgus of Sparta or Solon of Persia. To this day laws as enunciated in the Manusmriti excite the admiration of the world and elicit spontaneous obedience and conformity. But to our constitutional pundits that means nothing.”

When attempts were made under the stewardship of Ambedkar and Nehru in the late forties to give limited rights to Hindu women in property and inheritance through the passage of the Hindu Code Bill, Golwalkar and his associates had no qualms in launching a movement opposing this historic empowerment of Hindu women which was to take place for the first time in history. His contention was simple: This step is inimical to Hindu traditions and culture.

One can go on enumerating instances highlighting the ideological limitations of the Golwalkarian project which acted as a hindrance to the building of modern India. It is clear to any impartial observer that the way he tried to divide a wedge between the broad unity of the Indian people on the basis of religion, the way he lauded experiments in ethnic cleansing in Western Europe and the way he glorified Manusmriti till his end, demonstrate that his project was essentially inimical to the cause of social harmony.

It is a different matter that despite espousing a sectarian agenda the Golwalkarian project of remaking of Indian society continued to move ahead, albeit slowly. The “success” of the Golwalkarian project in winning over a chunk of our society to its side, definitely demands a separate treatment beyond this note.

Not that the Sangh had second thoughts about his vision, they rather continued to show their adherence to it by organising the “successful experiment” in Gujarat in 2002 or how the CAA-NPR-NRC triad represented the culmination of Golwalkar and RSS' vision. The only problem they have is the presentation of the vision. Looking at his controversial pronouncements from time to time on various issues of social-political concern and his transcending of the ‘calculated ambiguity’ on many occasions—a hallmark of the organisation which he built—it is not surprising that he has always come under a barrage of attacks from all those who opposed the Hindutva project.

The best strategy seems to be to disremember him in public and fully implement his essence in practice.