They’re selling postcards of the hanging

They’re painting the passports brown

The beauty parlor is filled with sailors

The circus is in town

Here comes the blind commissioner

They’ve got him in a trance

One hand is tied to the tight-rope walker

The other is in his pants

And the riot squad, they’re restless

They need somewhere to go

As Lady and I look out tonight

From Desolation Row

-‘Desolation Row’, Bob Dylan

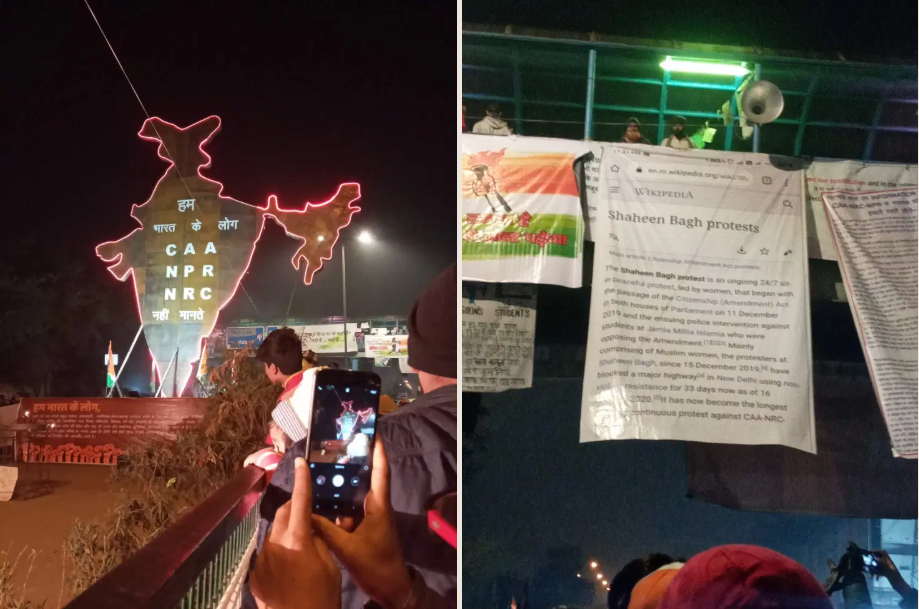

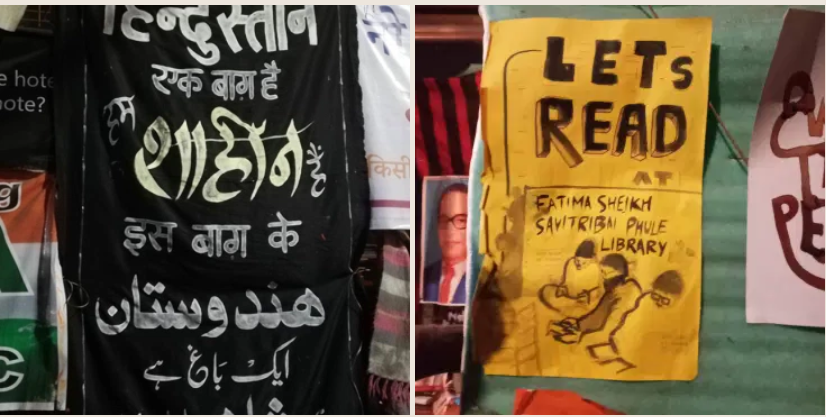

On 11 February, results day of the Delhi Assembly elections, the road to the protest site in Shaheen Bagh was filled with protestors with black bands around their faces and placards saying, ‘Aaj maun dharna hai. Hum kisi party ko support nahi karte hain.’ (Today is a silent demonstration. We don’t support any political party.) The day before, students from Jamia had been thrashed, abused and detained by the police to prevent them from carrying out a peaceful march to the Parliament.

It is more than 60 days since the women of Shaheen Bagh have been demonstrating against the Citizenship Amendment Act and the National Register of Citizens. They have reiterated again and again that no political party backs them, nor do they support any political party. No political party has come forward to have a dialogue with them till date. Was the silence of the protestors on 11 February a technique, a protest or a voice saying that you can’t silence us?

This set of fragments from December 2019 to the present is our attempt to think through what it means to live in a city of dissent and a city under siege. The piece is as much about the making of the iconic protest site of Shaheen Bagh as about emergent forms of life, publics and place making in a city, and a nation, being reconfigured by the normalization of barricades.

A friend from faraway writes to me to find out the names of the artists who have made the posters, installations and other artworks at Shaheen Bagh. I tell her that there are so many of them and yet no one person in particular. Everyone is doing something—painting, drawing, welding, writing, making. Whose idea, whose imagination, whose materials, whose labour, whose dissent has gone into what? What transformed construction debris into words, a Wikipedia page into a political banner, paper boats into hope, a road into a zone of care and freedom? The Delhi Police faced a similar dilemma when it wanted to speak to the ‘organizers’ of the protest—who are the leaders, who are not, who are the protestors, who are not, who are the supporters and who are the spectators. Where does the protest begin and where does it end? Does it begin from across the Yamuna in Delhi and end in Mumbra in Maharashtra? How many worlds does it create in its mimesis and alterity?

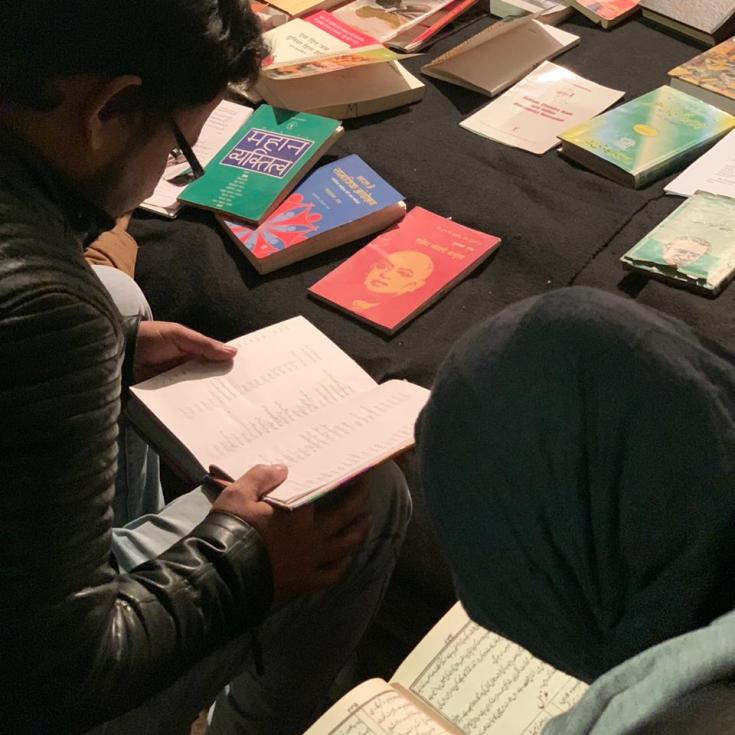

Shaheen Bagh is a sit-in, it’s a candlelight march, it’s a women’s space, it’s a library, it’s a metro station we had never been to. It’s a hangout zone, it’s a bus stop, it’s a night market, it’s an outpost. And it’s got parents with children and children with parents, it’s got teenagers and grandmothers, it’s got Sikh farmers from Punjab, it’s got Defence Colony, Mayur Vihar and Amroha. It’s got musicians, moongphali wallas, democracy wallas and family-outing wallas, it’s got the south Delhi wallas and the east Delhi wallas and the selfie wallas, it’s got Musalmans and Hindus, hipsters and dharam wallas, secularists and post-secularists, photographers and filmmakers. It’s got feminists and born-agains, sceptics and believers, it’s got Shias and Sunnis, it’s got Jamia and AMU. Even the Japanese came on some days. It’s got elites and super elites, communists and welders, traders from Seelampuri and poets from Kashmir, actors and dancers, it’s got working women, school teachers, beauticians and historians. It’s got Ambedkar and Gandhi speaking from the same dais.

It’s a cold winter night and another cold winter night, it’s many cold winter nights. It’s a legal electricity connection, a first house, it’s my uncle’s house, it’s an incrementally settled neighbourhood, a power of attorney house deed, a home loan, a political self. It’s erasure; it’s a coming out. It’s Facebook Live, Twitter feeds and Instagram stories, recording, archiving and circulating history as it is being made. It’s a home, a daily routine of sending kids to school, cooking and taking turns for household tasks, it’s a women’s protest, it’s shyness and anger, it’s ‘I have never spoken in a public place’, it’s ‘I have always been a housewife, but I am here’. It’s got lovers, ex-lovers, future beloveds, young first dates and old couples, making their way through and becoming the protest. It’s got songs, candlelight, mobile phone torchlights and flags, and more and more flags. It now has a nihari walla and an espresso walla. It’s got book nerds, armchair warriors, youth leaders and not-so-youth leaders. It’s conversations with Babasaheb and Bismil at the detention booth. It’s got angry young men and angrier young women. It’s got gentleness; it’s got shyness. It’s a road, a backyard, a mohalla, a mela, a movement, a metonym, a zenana, a qasba. It’s a city. It’s a public square; it’s a circle of friends. It’s two boys in the gully cursing the young wannabe poets. It’s the besuras and the sur wallas. It’s a soundscape, a camerascape.

And even when the mike stops working, it’s still shouting out clearly, ‘Azadi’.

In Manto’s story ‘Toba Tek Singh’, the madman, lies in the no-man’s land between two sets of barbwires, muttering and swearing, ‘Upar di gur gur di annexe di bedhiyana di moong di daal of di Pakistan and Hindustan of di durr phitey mun’, reflecting an incoherence that was possibly the only response to the bizarre travesty that the partition was. The madman laughs at the nonsensical marking of the border, the splitting of a people into two parts, an affliction that did not and will not end suffering in the futures of the split nations. Was the partition ever completed or did it continue to inhabit our cities, towns and villages in the form of religion- and caste-based neighbourhoods, working class slums and Muslim ghettos?

Was the nation cast in these continuously repeating barbwires, barricades and walls?

The madman outside Irwin hospital is explaining to no one his own histories of the city and of the police breaking people’s heads. He raises his hand up towards the sky and says, ‘They did this in the Emergency, then they did it in 1984, and now…they have done it again.’ His immediate reference is to the police brutality that has taken place at Turkman Gate, Daryaganj and Dilli Gate, this evening, as part of curbing the protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act. He’s moving between past state brutalities and the current one, imaginary speeches by dead politicians and the foretelling of futures, which he ascribes to the film star Rajesh Khanna, ‘Rajesh Khanna ne bola tha…yeh hoga’ (Rajesh Khanna had said this would happen), turning the current moment in Delhi to a predicted one. A few days later, he walks up to me and says, ‘I know what you are looking for… if you ever need to buy life insurance, contact my uncle in Kanpur…’ This incoherence, truth telling and dark futures are evocative of our movement into the singularity of the madman. With no forms of insurance left on our identities, we are caught in a fixed code, where we cannot be anything else, except the enumerated self of our names, our parents’ birthplaces and our religious identity.

Can we be anything but singular madmen and madwomen of the new partitions of the present and the future?

We are walking from Jamia to Shaheen Bagh, with candles and songs, and friends and strangers. The wind is very cold on our faces, the wind has been colder this year, but everyone is walking, coming out, standing in protest. A protest that has finally broken class barriers, gated communities, ghettos, and maybe even our fears. Maybe this is a fold in the ordinary; maybe this is the only apparatus we have. People are handing out candles, managing traffic, walking, singing, drifting apart and together at the same time, but hundreds are here, and thousands elsewhere, each doing what they can do, each turning up where they can. A group of young men pull out a long flag of India—we are walking under it, holding it up. It feels like a wedding, it feels like a funeral. Teenage boys chant ‘Azadi’, and the older women walking with them also join in. We are all friends, we are all strangers, we are all insiders, we are all outsiders, but we are all we have and each is the apparatus of the protest.

We are on our way to Shaheen Bagh and have gotten off the cab somewhere near a row of shops but are not sure which route to take to the protest area. It’s around 10 p.m. There are some men milling around a food joint and we ask one of them about the way to the protest, just as we would ask the way to an address, of a house or a shop. The man and others we stop to ask as we make our way into the alleys of the neighbourhood give us directions to the protest. When we return from the protest, way past midnight, we in turn give directions to people, on foot, in electric rickshaws, cars and cabs, to reach the protest site.

It’s a way we are all seeking.

As I am walking around the protest site, both inside the enclosure reserved for women protestors and around it, strangers strike up conversations with me, asking me where I have come from, thanking me for being there when they realize I am not from any of the neighbouring localities, bringing me tea and biscuits, asking me if I have eaten dinner and what time I ate. It’s heart-warming, it’s disorienting.

It’s like I am home.

We are looking for a friend who is also looking for us. We borrow a tricolour mounted on a crooked wooden pole from a little boy and wave the flag hysterically, while screaming, over the din of songs, chants and speeches, asking our friend on the other side of the phone to look out for the flag. The little boy insists on coming here every night, his father tells us. It is him who has put together the flag. Our friend finds us and we return the flag to the boy, thanking him.

It’s about finding friends in the city.

I am standing with friends, old and new, on the chalees futa road (40 feet road), sipping tea and talking politics and protests, despair and hope but also mundane matters of struggling with writing deadlines, what to cook for dinner and when this winter will end. All the while my eyes are trying to keep up with the buzz around me, the brisk business of restaurants, dhabas and chai shops, even a few kirana shops, in the middle of the night, the kids selling colourful polka dot balloons, the continuous stream of tiny processions, young boys with tricolour faces and flags in their hands moving on bikes, middle-aged men walking quietly in a line holding up posters in their hands, girls chanting ‘hum kya chahte…azadi’ slogans, fathers walking with daughters, a couple walking holding hands, the forever smiling chaiwalla keeping track of the endless orders for tea, the dhaba worker’s arms moving swiftly as he kneads atta, the strains of a song coming from somewhere close, mixing up with the laughter and chatter around me. It’s familiar; it’s new. I know I have been here before. I know I have been here before elsewhere. I know I have been here in a different time.

It’s a folding in of numerous chai ka tapris across the city that I’ve haunted with friends. It’s a folding in of nights of freedom spent with friends and strangers in JNU in the 2000s, even as I was studying in DU by the day. It’s a folding in of numerous protests, past and present, ragtag and massive, of citizens taking to the street.

It’s a folding in of the fantasy city where no place or time or idea is out of bounds.

It’s the end of January and the roads around my house are exploding with police in riot gear. The police buses came on 18 December 2019 and haven’t left since then. Their numbers have only swollen since then, as have the number of barricades. Barricades don’t allow any protest march to extend out, from the two exits of the road outside Jamia, into the city. The ghetto and its protestors are not to contaminate the city. Each time there is an attempt to march towards the Parliament or Gandhi Smriti, thousands of police prevent it from moving beyond this area. The daily presence of the police, with different kinds of weapons—guns, rifles, lathis and tear gas—that they are quick to use again and again, has become the new normal. In the police attack on protestors on 10 February 2020, many students claimed that the police had released a chemical that was not tear gas, causing nausea and fainting. The state has normalized its apparatus of control through the rampant imposition of Section 144, the clamping of Internet services, lathi-charges and beatings, large-scale detentions of protestors, denial of legal and medical aid to detained protestors, giving goons a freehand to beat, maim and shoot at students. This is the ordinary city, here and now, and not the place that can’t be named.

Are we to accept the barricades, the busloads of gun-toting police and the use of excessive force as the new ordinary? Does the folding in of the protest into the ordinary through repeated marches, banners, sit-ins, speaking up make the protest lose its impact as the analysts claim? Perhaps the protests have run their course in providing material for TV debates, academic papers, artist projects and hate speeches, so the people need to try something new. Perhaps, chanting the Hanuman Chalisa?

Has difference finally set itself in a quiet repetition? Has the apparatus of the state figured how to enumerate these differences? Are we fighting elections for schools and not for the rights of the protesting students? Is protest the only apparatus left that can march in the street, create the street and hold together democracy? Do we exist because we are alive or because we hold a piece of paper or a flag in our hands? Is repeating the chant of freedom our beauty, our bravery or our naiveté?