The present-day education reformers believe that schools are broken and market solutions are the only remedy. Many of them embrace disruptive innovations, primarily through online learning. There is a strong belief that real breakthroughs can come only through the transformative power of technology or the invisible hand of the market.

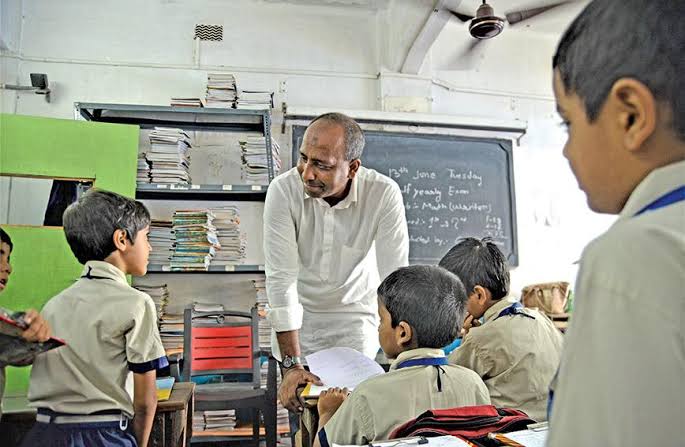

However, this strategy has not lived up to its hype and with valid reason. The youngsters need to believe that they have a stake in the future, a goal worth struggling for if they are going to make it in school. They need a champion, someone who believes in them, and this is where teachers enter the picture. The most effective approaches are those that foster bonds of caring between teachers and their students.

School dropout to educationist

Tikiapara, a sprawling slum in Howrah, is a witness and a willing participant in a quiet revolution led by Mamoon Akhtar that has the potential to turn around the lives of its residents, especially of its children.

Mamoon was forced to drop out of middle school because his parents couldn’t afford to keep him in school. Three decades later, he is the driving force behind a school in Tikiapara with 3,000 students, most of them children of unlettered parents.

Mamoon’s extraordinary journey from a victim to champion of the underprivileged started the day he decided that, just because his family couldn’t pay for his schooling, he wouldn’t forego education. His passion helped him overcome his deprivation.

“My father was a civil contractor. Our family fell on bad times when his business collapsed and I had to leave school. But I started giving tuitions and continued studying on my own. I would sit for examinations as a private candidate and this continued till Class XII, after which I had to give up because my father died and our financial condition got worse,” Mamoon recalls.

Mamoon’s father was keen that his son got a good education. So he put him in one of the area’s leading schools, St Thomas. After his father died, Mamoon took up a librarian’s job in a private school in Tikiapara, supplementing his income by giving private tuitions. Life would have gone on as usual but for the constant pricking of his mind that left him restless.

Mamoon couldn’t get over the tragedy he suffered on being forced to lose out on education. The young idealist believed in giving direction to the fire within, not in extinguishing it. In 1991, he started an informal class teaching 5-6 children in his own house in the Tikiapara slum. This began his lifetime romance with education. As the residents of the area became aware of this “school”, more and more children started coming and there was no place to seat them. Mamoon constructed a room on his own small plot of land (600 sqft).In that one room Samaritan Help Mission School was born with 25 young and eager children flocking to it. Mamoon stretched his every rupee and canvassed from door to door to raise Rs.28,000 per annum (in addition to his own contribution of Rs. 10,000). The organization has continued to steadily grow through the years.

The catchment area of Mamoon’s school is really horrifying; but Mamoon is alive and equal to the challenge. The parents come from very poor backgrounds, some are rickshaw-pullers and daily labourers. But with Mamoon’s effort, their dreams of educating their children in an English school became a reality. One of the most unsavoury things that Mamoon has to do is persuade their parents to stop selling drugs, resist the drug lords and pursue a dignified livelihood instead.

Social responsibility

As an educationist, Mamoon is also sharply aware of his role of a social reformer. Most children come from families afflicted with social maladies, with a large number of them being children of drug peddlers. Mamoon believes that schools should retain the right to exclude pupils as a last resort, in order to protect the other children in the class as well as teachers. But if a child is going to be excluded, it’s important that they are not excluded from education as a whole. The excluded children, Mamoon avers, can be affected by anxiety, depression, and loss of self-worth. There is decline in mental health and children become very reclusive. The stress of the exclusion also takes its toll on parents.

Mamoon knows the pain of deprivation. At a time when there is a widespread practice of “off-rolling” – pupils being shunted off a school’s roll in order to manipulate its exam results or rankings in league tables – Mamoon is doing his every bit to ensure than children remain at school during the day –their rightful place. There are hundreds of pupils who joined his school after being booted out of another one. Taking as many vulnerable pupils as possible – and never excluding them – is core to Mamoon’s mission. His school is single-handedly ensuring pupils are on the roll. There are a number of youngsters who wouldn’t be in education were it not for Samaritan Mission School. In a world where schools are clearly pushing vulnerable pupils out through the back door with little thought to their next steps and best interests, Mamoon is embracing them with a cheerful heart.

He emphasizes the involvement of parents in the learning process and provides a strong space for parents to monitor and contribute to their children’s learning. He believes the current school system has made communities passive recipients of whatever the government tosses at them, leaving them no say in the functioning of the school. People often believe that the problems in the education space have more to do with curricula or pedagogy, or with the capacity of teachers.

Mamoon believes that education is about creating the right ecosystem for learning to happen, and that community should be a critical part of that process. When families have a better understanding of learning processes, they try to provide an appropriate home environment so that students get the right encouragement. There is a need to lay a strong foundation at the elementary stage so that students are able to sail through secondary school with ease. He argues that enrollment should not be prioritized at the cost of learning, because it reduces schools to holding spaces where students are contained and fed, and they lose their role of imparters of learning. His main objective is to improving learning levels and promoting life skills.

With a little help from friends

Two incidents shaped Mamoon’s life. One day, he found a man beating up a woman because she refused to be a drug pusher. Mamoon tried to stop him and got beaten up himself. He was finally rescued by other locals who knew him and called him “Sir” because he taught children. The little boy whose mother Mamoon had tried to save caught up with him and simply said, “I want to study.” He asked the child to come to his house and soon he was running evening classes for 20 children in a spare room. To keep doing so, Mamoon went around the community seeking help and enlisted the services of local girls who had completed school as teachers at 100 per month.

Then, one day, he spotted a newspaper clipping which pictured a lady singing with a group of children. She was Lee Alison Sibley, the Jewish wife of a staff in the US consulate in Kolkata. Mamoon wrote to her, seeking help; she replied that he should ask the local community. Mamoon wrote again. Eventually, she came, saw what he was delivering from a single windowless room, was overwhelmed, wrote out a cheque for Rs 10,000 and asked a local journalist friend to write about his work. It highlighted the fact that Mamoon taught children from all communities.

When Mamoon canvassed for help from the community around him he also reaped a bonus —a strong connect with the community. In 2007 the Samaritan Mission School became accredited and recognized by the West Bengal government. Today it is a co-educational English-medium school, affiliated to the state board for secondary education, with an enrollment of 1,300. The big thing is “English-medium”; Mamoon knows the difference that makes.

The odds are stacked against the children of this locality given the inter-generational nature of poverty, and the poor developmental outcomes that families like these face. Unsurprisingly, these children struggle with the usual problems of first generational learners—poor academic achievement, inferiority complex, maladjustment, lack of initiative and an underdeveloped personality. Disheartened and discouraged by financial stress and their own inadequacy, parents are ill-equipped to adequately support their children. It is parental commitment to schooling that keeps children in schools, even at the cost of additional debts and hardships. But parents in Tikiapara have little motivation to invest in their children’s education. Fortunately, Mammon’s conviction and commitment is unflagging and his enthusiasm is contagious, sending ripples of hope in the community.

Today, SHM’s schools educate more than 3,000 children of different ages. Some are orphans; some have run away from home; all are underprivileged.SHM charges them five rupees a year because Mamoon believes that people will not value anything that is free. Funds to run the school come from Mamoon’s savings and private donors, and through word of mouth.

Now switch to I.R. Belilious Institution on Belilious Road, covering two acres of land bequeathed by a Jewish couple, Rebecca and Isaac Raphael Belilious (they both died childless), with a football field, basketball court, a water body, a two-storied school building and a bigger one coming up which will take classes up to Class 8. The whole complex comes under the Belilious Trust Estate. As a child Mamoon swam there, to later see the water body turned into a municipal garbage dump, the government school virtually defunct, the whole space gone derelict and become a den of drug pushers.

The land on which the second SHM school stands had thus been a garbage dump for years until Howrah City Police and the Howrah Municipal Corporation got together to create a conducive atmosphere for Mamoon to expand his initiative. The police helped them (Mamoon and his staff) build a wall, remove encroachments and start a school there. The local police head played the key role in transforming the place into a site suitable for a school.

Creating safe spaces for children at risk

With lots of activities going on and off the court, the kids forget their everyday problems of abusive households. Mamoon and his team zero in on teenagers who are on the verge of dropping out. Left to their devices, odds are that they will wind up on the streets or in jail. These programmes and many others with a similar philosophy have realized that often kids just need extra time or more flexibility to re-engage with education.

Many children studying in Mamoon’s schools attest to the fact that it has a fun-filled, interactive and encouraging atmosphere and that the teachers are extremely supportive. Children are also engaged in other creative activities like sports events, quiz competitions, picnics and recreational programmes in the local parks. Regular cleaning campaigns in Tikiapara are organized in which students, teachers and other volunteers take an active part. Mammon believes that regular participation in extracurricular activates can radically improve the life chances of young people. With this in mind, he has set up sports, drama, painting and debating clubs that provide opportunities for children to learn the behavioural and emotional skills that will help them succeed later in life too.

The school gives them the space and environment to know that they can become something and each one of them will indeed become something. The school has a range of subjects to choose from based on the strengths of the pupils, but they are required to study a number of key subjects regardless of chosen streams. There are a range of practical workshops on common everyday skills like basic woodwork, plumbing, sewing, embroidery etc. The focus is not simply on attainment and “resilience” –the current buzzword – but on producing confident, well-rounded citizens who feel as though they belong and have value in society. There is also an attempt to move away from rote learning where kids are mostly taught to memorize information.

“Many people suggested that I turn my school into a Bengali, Hindi or Urdu-medium institute, but I insisted on an English-medium school. Knowing English is very important in the current scenario,” the 43-year-old said. Scores of parents are grateful that Mamoon stuck to his plan. Sending their children to any other English-medium school in the area would have been ten times more expensive.

Mamoon’s policy of inclusive education has ensured that the constitutional right to primary education is a reality in this dark slum. There are schools who see parents as an easy touch or not well-educated and are approached informally and told it “will be difficult for their child to stay”, in the hope the parents agree to moving or home-schooling their child. But Mamoon’s schools are a safe learning haven where no one is shunned –either on the basis of creed or financial standing.

Mamoon’s three daughters –seven-year-old Atifa Fatema, six-year-old Adiba Fatema and four-year-old Batul Fatema– also study at Samaritan Help Mission School. When wife Shabana readies the three girls for class every morning, he can’t help but wonder what life might have been if he weren’t himself asked to leave school midway.

Mamoon says that the process of teaching and learning is an intimate act that neither computers nor markets can hope to replicate. Small wonder then that the business model has not worked in reforming the schools as there is simply no substitute for the personal element. The school puts great emphasis on sensitizing parents. There is no substitute for a good teacher and nothing more valuable than quality classroom instruction. But, Mamoon feels, we also need more involved parents to make leaning more effective.

The blame for the dire state of India’s education is usually heaped upon bad infrastructure, poor student attendance, teacher absenteeism, inputs-based monitoring, and inadequate teacher preparation programmes. While these issues are valid, Mamoon believes they do not fully explain the learning crisis apparent in our classrooms. The real driver of change at the school level, according to him, is the culture of learning that teachers and educationists bring into schools.

Entrepreneurs like Mamoon can bring about a radical shift in teaching models, despite the ebb and flow of education reforms. They are in the forefront of innovations that are breaking the mould and daring to free teachers from the shackles of curriculum dictates. In the process, they are giving students and educators the power to become masters of their own learning.

In a world where social issues are proliferating, where governments are looking inward instead of outward, hope comes from social entrepreneurs like Mamoon whose commitment and creativity aredriven by a purpose far bigger than their own identity. They work in an environment where the system does not consistently provide the best solutions, nor does it help to refine or support scaling them. Then there are other fundamental issues: capital for innovation and growth is woefully inadequate, fear of failure encourages only incremental change and competition overrides collaboration.

A lot of good programmes got their start when one individual looked at a familiar landscape in a fresh way. What they did was to simply change the fundamental approach to solving problems, and the outcomes have been truly revolutionary. Thus, people only need to summon their will-power the way game-changers like Mamoon Akhtar are doing to bring about change.