As a journalist, Ambedkar worked towards liberating the India of the outcastes (Bahishkrit Bharat) and building a new, enlightened India (Prabuddha Bharat). Dr Siddharth contributes the first piece to a special series in the run-up to the centenary of the launch of ‘Mooknayak’.

DR AMBEDKAR’S JOURNALISM MODEL

After resigning from the Union Cabinet on 27 September 1951, Dr Ambedkar issued a statement explaining his decision. On 10 October 1951, he issued this statement outside Parliament because he was unwilling to provide an advance copy of it to the speaker. He said that he was issuing the statement for three reasons. After giving the first two reasons, he said, “Thirdly, we have our newspapers. They have their age-old bias in favour of some and against others. Their judgments are seldom based on merits. Whenever they find an empty space, they are prone to fill the vacuum by supplying grounds for resignation which are not the real grounds but which put those whom they favour in a better light and those not in their favour in a bad light. Some such thing I see has happened even in my case.” (Sharmila Rege, p 258).

Clearly, Ambedkar was so perturbed by and convinced of the biased and subjective outlook of the newspapers and their penchant for ignoring facts that he thought it prudent to make his stand clear in black and white. Dr Ambedkar’s statement points at four facts. One, even in 1951, the Indian newspapers were characterized by a biased and subjective outlook. Two, their reports were not based on facts; three, they twisted facts in such a manner so as to enhance the image of their favourites and show those whom they did not favour in bad light; and four, that even a person of Dr Ambedkar’s stature could become the victim of irresponsible and motivated journalism. It must be remembered that besides having been the chief architect of the Constitution, Ambedkar was a former union minister, a Member of Parliament and one of the top leaders of the country. But even then he was not sure that the newspapers would give him fair treatment.

In his statement, Dr Ambedkar refers to the “age-old bias of newspapers”. It is not difficult to guess that he is talking about the centuries-old prejudices born of the caste system. Also, he indirectly enunciates the basic principles all newspapers should adhere to: that their reports should be free from bias, they should be based on facts and that they should not lionize or vilify a person on the basis their own likes and dislikes.

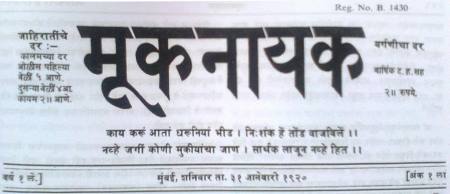

Almost a century ago, Dr Ambedkar realized that most of the Indian newspapers were steeped in caste-based prejudices and that their writings were unfair and motivated. He had first expressed his views on newspapers in the editorial of the inaugural issue of Mooknayak, published on 31 January 1920. He wrote, “If we throw even a cursory glance over the newspapers that are published in the Bombay Presidency, we will find that many among these papers are only concerned about protecting the interest some [upper] castes. And these can’t care less for the interest of other castes. This is not all. Sometimes, they go against the interest of other castes.” (Mooknayak, p 34). Since most of the newspapers harboured casteist prejudices and biases and were hurting the interests of the “other castes” (the outcastes), Dr Ambedkar felt the need for a newspaper that would protect their interests. He wrote, “There is no better source than the newspaper to suggest the remedy to the injustice that is being done to our people at present and will be done in future, and also to discuss the ways and means for our progress in the future” (ibid). At another place in the same editorial, he wrote: “It is clear that in the absence of authority and knowledge non-Brahmins remained backward and their progress was arrested but at least poverty was not their lot because it was not difficult for them to earn their livelihood through agriculture, trade and commerce or state services. But the effect of social inequality on the people called Untouchables has been devastating. The vast masses of Untouchables are undoubtedly sunk deep into the confluence of feebleness (helplessness), poverty and ignorance” (ibid, p 33).

The masthead of the first issue of ‘Mooknayak’

The masthead of the first issue of ‘Mooknayak’

It was to apprise the world of the kinds of atrocities being committed against the Untouchables and the ways and means of their liberation that Dr Ambedkar had decided to bring out Mooknayak. What needs to be emphasized is that he did not allow Mooknayak or any of the four other newspapers he published to become carriers of casteist prejudices. That was because he believed that what was hurtful to any particular caste was hurtful to society as whole. He likened society to people travelling on a boat. Warning the casteist newspapers he wrote, “If any one caste remains degraded it will have an adverse effect on other castes, too. Society is like a boat. Suppose a sailor, with the intent of causing some harm to the other sailors or while playing a prank, punches a hole in their compartment, the result will be that along with the other sailors he will also drown sooner or later. Similarly, a caste which makes other castes suffer will also undoubtedly suffer directly or indirectly. Therefore, newspapers that pursue their own selfish interests should not follow the example of a fool who deceives others and protects his own interests” (ibid p 34). Declaring that he did not intend to “follow the example of a fool who deceives others and protects his own interests” Dr Ambedkar made it clear that his newspaper was not meant for hurting the interests of any caste or community but for building a society in which anyone does no harm to others but instead protects their interests.

Besides the casteist outlook of the newspapers, the commercialization of journalism and the immoral conduct of journalists were also matters of deep concern to Ambedkar. He expressed his anguish in these words: “Journalism in India was once a profession. It has now become a trade. It has no more moral function than the manufacture of soap. It does not regard itself as the responsible adviser of the public. To give the news uncoloured by any motive, to present a certain view of public policy which it believes to be for the good of the community, to correct and chastise without fear all those, no matter how high, who have chosen a wrong or a barren path, is not regarded by journalism in India its first or foremost duty. To accept a hero and worship him has become its principal duty. Under it, news gives place to sensation, reasoned opinion to unreasoning passion, appeal to the minds of responsible people to appeal to the emotions of the irresponsible … Never has the interest of country been sacrificed so senselessly for the propagation of hero-worship. Never has hero-worship become so blind as we see it in India today. There are, I am glad to say, honourable exceptions. But they are too few and their voice is never heard” (B.R. Ambedkar, 1993).

Thus, Dr Ambedkar’s seeks to lay down some standards for Indian newspapers. They are:

- Journalism should be fair and unbiased. In the Indian context, it also means being free from casteist biases and prejudices.

- Journalism should be based on facts rather than on pre-conceived notions.

- Journalism should be a mission, not a trade or business.

- Journalism and journalists should have their own moral standards.

- Fearlessness is an essential characteristic of journalism and journalists.

- Advocacy in social interest is a prime duty of journalism and journalists.

- There should be no place for hero worship in journalism.

- Objectivity, not sensationalism, should be the ideal of newspapers.

- Instead of whipping up passions, the journalists should strive to evoke the reason of society.

B R Ambedkar

B R Ambedkar

Dr Ambedkar felt that the outcastes were in acute need of newspapers of their own. He wrote, “The Untouchables have no press. The Congress press is closed to them and is determined not to give them the slightest publicity for obvious reasons” (B.R. Ambedkar, 1993). But he knew equally well that the outcastes do not have the wherewithal for starting a newspaper. He expressed his concern thus: “It is depressing that we don’t have enough resources with us. We don’t have money; we don’t have newspapers; throughout India, each day our people are suffering under authoritarianism with no consideration, and discrimination; those are not covered in the newspapers. By a planned conspiracy the newspapers are involved full-fledged in silencing our views on socio-political problems” (Ambedkar, 1993). He was also aware of the fact that not only the newspapers but also the news agencies were owned by upper-caste people. Quoting an example, he wrote, “The staff of the Associated Press of India, which is the main news distributing agency in India, is entirely drawn from Madras Brahmins – indeed the whole of the press is in their hands and who, for well known reasons, are entirely pro-Congress and will not allow any news hostile to the Congress to get publicity. These are reasons beyond the control of the Untouchables” (Ambedkar, 1993).

An in-depth study and analysis of the nature and character of Indian newspapers and the realization that the Untouchables needed a newspaper of their own for protecting their interests made Ambedkar enter the field of journalism. He was well aware of the kind of challenges and difficulties a resource-less community would face in bringing out a newspaper. Yet, he accepted the challenge and launched his first newspaper, Mooknayak, when he was 29. And all his life, he remained associated with journalism. Newspapers were an indispensable weapon for him in his struggle.

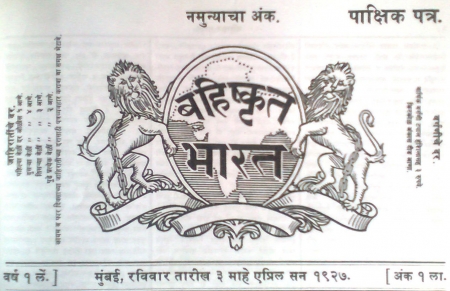

The masthead of the first issue of ‘Bahishkrit Bharat’

The masthead of the first issue of ‘Bahishkrit Bharat’

He did journalism for around 36 of the 65 years he lived, albeit with gaps. This period fell between 1920 and 1956. Mooknayak’s inaugural issue was published on 31 January 1920 and the first issue of Prabuddha Bharat came out on 4 February 1956. In between, he launched Bahishkrit Bharat (India of the outcastes) on 3 April 1927, Samata on 29 June 1928 and Janata on 25 November 1930. His journey from Mooknayak to Prabuddha Bharat was both a journey of ideas and struggle. The “Mooknayak” (hero of the voiceless) saw their liberation in ‘Prabuddha Bharat’ (Enlightened or awakened India). His journalism began with becoming the voice of the voiceless through Mooknayak and ended with the dream of building an enlightened India through Prabuddha Bharat.

Well-known scholar Gail Omvedt, who has studied Ambedkar in depth, says that he dreamt of building a new India. She writes, “Dr Ambedkar lived and worked in the first half of the 20th century. That was the period when the Indian freedom struggle was in its decisive phase. But Dr Ambedkar’s struggle was for a different kind of freedom. It was the struggle for the freedom of the most distressed class of Indian society. His freedom struggle was broader and deeper than the freedom struggle that was being waged against colonial rule. He wanted to build a new nation.” As Dr Ambedkar’s journalistic writings and the newspapers that he launched show, he worked for the liberation of the outcastes and also for building a new India. He knew that the liberation of the “Bahishkrit Bharat” and the making of the “Prabuddha Bharat” were synonymous.

References

- Rege, Sharmila. Manu ki Vikshipta ke Virudh, Chayan Evam Prastuti, trans Anupama Gupta, The Marginalised Prakashan, 2019

- Ambedkar, B.R., Mooknayak, Trans. Vinay Kumar Vasnik, Samyak Prakashan, 2019

- Babasaheb Dr Ambedkar: Sampoorn Vangmay, Dr Ambedkar Shanti Pratisthan, New Delhi

- Omvedt, Gail, Dr. Ambedkar Prabuddha Bharat ki Aur, Penguin Books, New Delhi, 2005

- Ambedkar, B.R, Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Government of Maharashtra, 1993

- Keer, Dhananjay, Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Jeevan-Charit, Popular Prakashan, Mumbai 2018

- Moon, Vasant, Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, National Book Trust, 1991

- Shahare, M.L. and Anil, Nalini, Babasaheb Dr Ambedkar ki Sangarsh-Yatra Evam Sandesh, Samyak Prakashan, New Delhi, 2014

- Ambedkar, B.R., Mooknayak, trans and ed Sheoraj Singh Bechain, Gautam Book Centre, Delhi 2019

- ‘Bahishkrit Bharat’ mein Prakashit Babasaheb Dr Ambedkar ke Sampadkiya, trans Prabhakar Gajbhiye, Samyak Prakashan, New Delhi, 2017

Translation: Amrish Herdenia, copy-editing: Anil.

This article was first published on January 26, 2020.