New Delhi: Away from the revelry and new year parties, protesters at Shaheen Bagh and Jamia Millia Islamia in the southeast district of New Delhi braved the coldest December of the century to “protect the spirit of the Constitution.” Their foremost concern remains the possible loss of citizenship in the wake of the divisive Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the upcoming National Population Register (NPR).

They say in equivocal terms that they have no reason for celebration at a time when their very “existence is in crisis” as the proposed National Register of India Citizens (NRIC), based on the data compiled through the NPR, has already been notified by the government. Muslims especially fear that they would be the first to be disenfranchised through the proposed NRIC. The non-Muslims — they argue — who are excluded from the final citizenry register would be given back Indian citizenship through the CAA, which seeks to grant Indian nationality to non-Muslim migrants from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh.

The protesters allege that the CAA, NPR and the proposed NRIC will discriminate against the minority Muslim community and chip away at the country’s secular Constitution.

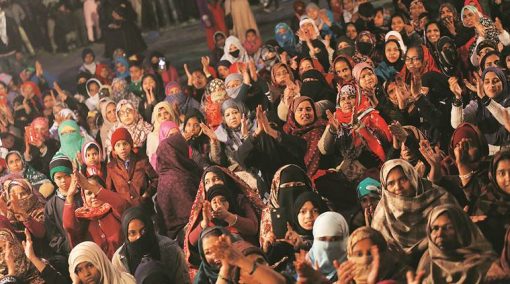

Though protests have been going on across the country since the CAA was passed, Shaheen Bagh and Jamia Millia Islamia (which protesters have begun to refer to as Shaheen Square and Jamia Square, in a nod to the Tahrir Square of the Arab Spring) has perhaps become the epitome of the resistance. Agitators (predominantly women) at both these sites have constantly reiterated one message over the past 16 days and chilly winter nights: NO CAA, NO NPR, NO NRIC!

On Monday, the coldest day in a century (when the maximum temperature was 9.4 degrees Celsius) both sites witnessed huge turnouts amid poetry recitals, chanting of charged slogans, plays and speeches.

20-day-old Umme Habeeba is the youngest agitator at Shaheen Bagh. Her mother Rehana, when asked how she comes to the protest site every day with her five children, says, ““Habeeba badi ho kar puchegi ki ammi jab humpe zulm ho raha tha tab aap kya kar rahin thin, to main kya jawab dungi use (when Habeeba grows up and asks what I was doing when people were being oppressed, what will I tell her?)”

“Samvidhan bachana hai, baithenge (We will sit as we have to protect the Constitution). This is our nation, our land. We have to protect it. We aren’t going anywhere,” she says with the conviction that the protest will be called off only after the government withdraws the controversial CAA, NPR and the proposed NRIC.

The hundreds who have been at Shaheen Bagh throughout the day since December 15 brave the cold with the help of electric heaters, mattresses, blankets, tarpaulin sheets and loads of chai (tea).

Among them is an 82-year-old woman who always refuses to give her name. “I won’t give my name to you or anyone else. And I am not going to show my papers to anyone to prove my relation to this soil. Yeh mulk mera hai (this is my country),” she says, refusing to talk much and instead concentrating on the speeches being made. She defiantly refuses to take any blankets despite the cold.

It won’t be an exaggeration to say that girls and women of all ages are the spine of the spontaneous protests at Shaheen Bagh.

Take Noor Jahan, for instance, who in a few words sums up why she is part of the protest. “Why am I sitting here? In this cold? To claim the ground under my feet, to claim the roof over my head, to claim the fire in my kitchen, to claim the sky and this air, to claim the future of my children.”

It has been two weeks since Maryam Khan spent a night at home. She has come here to express her fierce disagreement with the country’s new citizenship law. This is the first time that Maryam has participated in any kind of protest. She is usually extremely busy looking after her two young daughters. But she says she has come to take part in the protest for the future of her children.

“I don’t know what my daughters are up to. I don’t know what is happening in my house. My country needs me right now. I am the voice of all these women sitting here and they are mine,” she says, suddenly lending her ears to a speaker who is sharing some piece of information from the stage.

The protestors keep themselves busy with chanting slogans, singing revolutionary songs and even reciting the preamble of the constitution. Residents are crowdfunding resources to provide medicines, food and refreshment to the agitators, and standing guard around the protest site.

Dr Mohammad Ahmad, a physician, spends all his time after work giving medicines to the protesting men and women. “After my hospital hours, I, along with two paramedics, come here to provide medical assistance to the protestors. We have all the basic medicines. Generally, we get patients who are suffering from minor seasonal ailments. If anyone in a serious condition comes to us, we refer them to a nearby hospital after giving first aid,” he says.

Dr Harjit Singh Bhatti, former president of the Resident Doctors’ Association, AIIMS, had also tweeted about the health camp. “Doctors, nurses, medical volunteers with ambulance and medicines will be there,” he tweeted.

The police, according to the protesters, have told them several times to disperse but they are defiant. “We don’t fear the police. This law is against us. That is why we have come out on to the streets,” says Zahida Khatoon.

“Our passion for the country is keeping us here. We are ready to sacrifice anything. We are willing to suffer but won’t sacrifice our independence,” says another protester.

The mood is upbeat in Shaheen Bagh. Though the government has not shown any sign of back peddling, the protesters are confident of victory. They say there is too much at stake for anything less.

The protest site at Jamia Millia Islamia appears to be more regulated, with mobilizations taking place strictly between 11 am and 7 pm. One carriageway of Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar Road, which separates the university campus into two parts, is blocked while the other side is open for traffic.

A huge flex with the preamble of the Constitution hangs near gate number 7 in front of which there is a designated area for speakers. People (students as well as locals) throng the protest site every day to extend solidarity to those opposing the controversial legislation and brutal police crackdown the students.

On December 29, among the events at the site was a street play titled "Jamia Wala Bagh — students under siege." Presented by Jamia Hamdard Alumni Association, the play depicted the police brutality on the students who were at the university library. It drew parallels between the police action against students and the violence during British rule. It was performed before a crowd of over 500 people, most of whom wore white bandages on their eyes in solidarity with Minhaj, who allegedly lost an eye during the violence on campus.

The Jamia Coordination Committee, a group of around 50 volunteers, students and alumni, and residents, manage the crowd and traffic. They ensure the smooth passage of vehicles and that no one suffers any inconvenience due to traffic jams.

After day-long speeches, music and slogan chanting, the protest ends in the evening with an announcement that everyone will reassemble at the same place the next day. After people leave, a group of volunteers clean the entire area, picking up food packets, tea cups and other waste material left behind.

Later in the night, the only indication that this is a site of protest is the series of banners and posters on the fences on both sides of the road — including a photo exhibition of 80 images from Mahatma Gandhi’s life and a banner with people’s signatures and their messages to the government.