A list of significant dates marks the life and after-life of the Babri masjid. A new date—9 November—was added to that list this year. It has, within weeks, relegated 6 December, the day on which the Babri masjid was demolished 27 years ago, in the hierarchy of importance. Those who recall the interminable absence of the Babri masjid need to wonder whether 9 November is a more appropriate date than 6 December to do so.

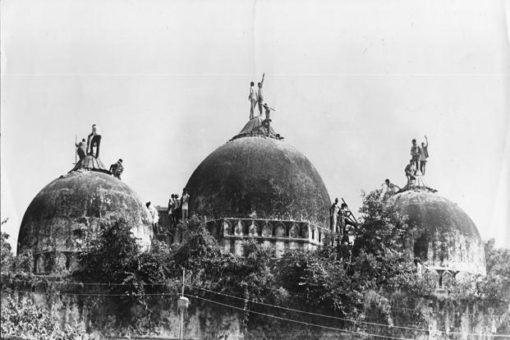

On 6 December 1992, the Babri masjid disappeared from Ayodhya’s landscape. Yet any hope of its return from after-life was dashed on 9 November 2019, the day on which the Supreme Court paved the way for building a Ram temple at the site where the Babri masjid had stood.

For a minute, imagine the Supreme Court had restituted the disputed site to the Muslims. It would have denuded 6 December of much of its original meanings. The anniversary of the demolition of the Babri masjid, after all, is also commemorated to remind the nation about the usurpation of a place of worship, through deception and violent tactics, in violation of the Constitution and its secular ideals.

Hope lingered among the devoutly religious as well as the constitutionalists, Muslims and Hindus alike, that the Supreme Court would restore the Babri masjid site to Muslims, leaving to them the option of deciding whether to rebuild the mosque there. Or, alternatively, freeze construction on the 1,500 square yards on which the Babri masjid had stood.

The Supreme Court, in its wisdom, decided otherwise. If 6 December is about remembering the injustice done to Muslims and subversion of the Constitution, then these have been given an official imprimatur by the Supreme Court, regardless of the tedious logic and pious homily it employed to justify its verdict.

The purpose of celebrating or commemorating an anniversary is to convey the subliminal message inherent in a past occurrence. This is why a cruel choice awaits those who mourn on 6 December: should they commemorate the demolition of the Babri masjid on the day on which injustice was perpetrated? Or on the day the injustice was whitewashed as justice?

From this perspective, 9 November has a far greater import than 6 December and, therefore, is better suited to be observed as an anniversary.

It does seem a ridiculous idea to construct multiple anniversaries around a structure, whether religious or secular. The memory of the Babri masjid, as such, weighs under the burden of dates, each crying out to be remembered.

For instance, on 29 January 1885, Mahant Raghubar Das filed a suit for constructing a temple on the chabutra, or raised platform, which he had erected soon after the revolt of 1857. Although his suit was dismissed, the legal history of the dispute over the Babri masjid begins from this date. Thus, 29 January 2035 will mark the 150th year of the first legal challenge to the ownership of the Babri masjid.

At least two other dates contend with 6 December and 9 November for commemoration. On the night of 22-23 December 1949, idols were placed in the Babri masjid, triggering a chain of events which culminated, after several decades, in the judgment of 9 November. As important a date is 1 February, on which day in 1986 KM Pandey, the district judge of Faizabad, ordered the opening of the locks on the gates of the Babri masjid. Pandey’s order turned a local dispute between two communities into a pan-India one.

These multiple dates, in the life and after-life of the Babri masjid, have the same equivalence as the dates of separation and divorce have for a couple when one of them decides to end their marriage. This analogy is more than apt as the history of the Babri masjid has come to symbolise the relationship between Hindus and Muslims in our era.

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and its affiliates have sought to unilaterally severe the relationship. This is manifest in the Sangh marking 6 December as Shaurya Diwas, or the day of valour. It is the equivalent of a person celebrating the date of divorce as his or her day of liberation.

Indeed, the 9 November judgment will invariably spawn a new calendar of anniversaries—the date on which the foundation of the Ram temple will be laid, for instance; or the date on which the idols will be installed in the sanctum sanctorum; or the date on which the temple will be thrown open to people. It will likely be a resplendent show, beamed live on TV, and watched in every house.

It will be akin to a second wedding for one of the divorced partners; for the other, a miasma of memory to battle.

India is already set on the path of inventing a new set of anniversaries, which will be celebrated by a segment of Hindus and mourned by Muslims and liberal Hindus. This is because the 9 November judgment has not brought a closure to all outstanding disputes between Hindus and Muslims over places of worship, evident from the absence of an unequivocal avowal by the Sangh on this count.

The Hindutva intelligentsia is jubilant that 9 November judgment has established a precedent for undoing what is described as historical injustices. For instance, in the 1 December edition of The Times of India, Rahul Kaushik and Shubham Tiwari listed Kashi Vishwanath in Varanasi and Krishna Janmabhoomi in Mathura as “examples of historic injustices against the Hindu civilisation.”

They then concluded: “This decision [9 November judgement] provides solace to the Hindu civilisation from wounds inflicted by religious fanatics [Muslims]. Hopefully it will be a new precedent where there is a collective responsibility for such past wrongs and an effort to undo them at the earliest.”

It is time to replace 6 December with 9 November for commemorating the disappearance of the Babri masjid and the many symbolical meanings associated with it; and also perhaps for anticipating the grim future awaiting the nation.