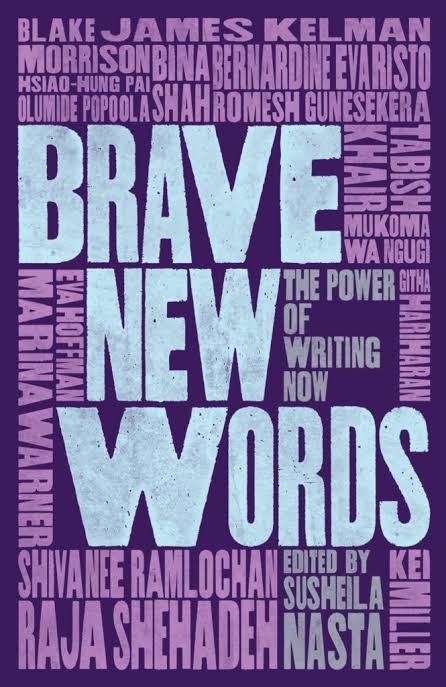

Edited by Susheila Nasta, Brave New Words: The Power of Writing Now is an anthology of fifteen specially commissioned essays from distinguished authors who explore the value of critical thinking, the power of the written word, and the resonance of literature in the twenty-first century. Their work articulates “brave new words” at the heart of battles against limitations on fundamental rights of citizenship, the closure of national borders, fake news, and an increasing reluctance to engage with critical democratic debate.

The following are excerpts from Bina Shah’s essay “The Life and Death of Pakistan’s Sabeen Mahmud” and Tabish Khair’s essay “The Bravado of Books”.

From The Life and Death of Pakistan’s Sabeen Mahmud

–Bina Shah

Pakistan is not an easy place to have an opinion, and it can sometimes result in your death. At least, that’s what people said when Sabeen Mahmud, the 40-year-old human rights activist and founder of The Second Floor, was killed in 2015. The assassination of Sabeen Mahmud resulted in the silencing of a voice, and then, paradoxically, the amplification of many others, raised in protest and anger and fear and sorrow. Yet it also illustrates the deadly struggle in Pakistan for freedom of opinion, thought, and action: precious values in open, democratic societies which are seen by many in this deeply conservative country as threats to national security, and perfidy to the country’s core values…

There is a well-known photograph taken at the scene of the crime: Sabeen’s Kohlapuri sandals abandoned in the well of the driver’s seat in her car. It speaks louder than the gunshots which entered her body, in her chest, cheek and neck, killing her immediately. A final sigh, a slumping of the head to the left, and silence. A brave voice gone forever— this is Pakistan’s curse.

In 2007 Sabeen left a successful career in IT to start a movement for positive social change in Pakistan and opened The Second Floor in Karachi, a unique space where she proffered dialogue, critical thinking, the arts and science along with low-priced cappuccinos and cookies. Over the years the café became a breathing space in a city wracked by years of political violence. People of all generations went there to talk, to dance, to create art, to practise yoga, to listen to lectures on quantum physics, politics and philosophy. Things that seem normal to anyone living in a ‘normal’ country, but Pakistan is not a normal country.

In Pakistan, ‘normal’ is a shifting paradigm. What is normal when a country has been born out of a violent earthquake, the cleaving of a nation in two, the transfer of millions and the death of millions? Historian Ayesha Jalal gets to the heart of what happened to Pakistan both before and after Partition, which set it on its path of military rule, itself only one iteration of that abnormality. ‘When Pakistan was created, it got a financial structure that was 17.5 percent of undivided India, and a military that was one-third of undivided India,’ she wrote in Scroll.in. In other words, the army’s prominence in Pakistan is a structural reality of Partition, as Jalal notes: ‘Pakistan is a state that was not supposed to survive. The real history is that it did manage to survive. Military dominance is the price Pakistan has paid for its survival.’

[…]

That they chose to kill a prominent woman activist is less about eliminating Sabeen the woman, and more about angry young men—intelligent bit players trying to prove their influence over Pakistan’s social fabric. Religious objections to a ‘secular’ space may have only been part of this story. While some accept the police-recorded confessions of Saad Aziz and his cohorts claiming Sabeen’s secularism as the reason for her murder, others maintain the state had her killed for hosting the discussion on human rights violations in Balochistan.

Pakistanis have learned over the years never to accept official explanations for major events, especially high-profile assassinations (former prime minister Benazir Bhutto’s 2007 murder still remains a mystery), as the state often acts to protect those people complicit in the attacks. Nor do the Pakistani people trust the state to resist the lure of extra-judicial murder when it comes to silencing an opponent. Some in the intelligentsia thought Sabeen was silenced by the state; over the past ten years people have grown suspicious that anyone who promotes Pakistan’s nascent civil society and social consciousness does so as a ploy for foreign money, or is a traitor who wants to destabilize the nation. Sabeen’s murder was seen by some as retribution for these imagined crimes.

One of democracy’s key values is inclusion, and Sabeen worked hard for it, carving out a space for the people who couldn’t find a place for themselves anywhere in the traditional strata. Artists, students, philosophers, scientists, ordinary citizens and social activists alike found refuge and relief at The Second Floor and they also found themselves. Once they began to organise and raise their voices for reform, they became brave enough to challenge authority. They demanded accountability and transparency from the city’s administration, from the bureaucracy and, perhaps fatally, from the military.

[…]

From The Bravado of Books

-Tabish Khair

The bravery of the word is not just the bravery of the individual who uses it. For the individual has too short a life. She can mutter, under her breath, e pur si muove, but breath is short and fragile, inquisitions are long and powerful. The bravery of the word is enabled by the medium. To move unthinkingly to another kind of medium might enable other kinds of bravery—or cowardice.

Because, finally, the pen is not mightier than the sword. Authors love to fool themselves into thinking so, particularly authors of Literature. Some of it has to do with the author’s deep investment in Literature, and Literature’s deep investment in life. ‘Ragon mein daurate phirne ke hum nahi qayal / jab ankh hi se na tapka to phir lahu kya hai,’ wrote the great Urdu poet, Mirza Ghalib in the early nineteenth century (‘I don’t believe in its running about in one’s veins, / If it doesn’t drip from the eyes, it is not blood’). He was expressing a view of Literature as bearing witness (eyes: ankh) to the atrocities of the human psyche, the human heart. ‘Maata-e-loh-o-qalam chhin gayi to kya ghum hai / ke khoon–e–dil mein dubo li hain ungliyan maine’ wrote the revolutionary twentieth-century poet, Faiz Ahmad Faiz (‘Why sorrow because my tablet and pen have been snatched away / I have dipped my fingers in the blood of my heart’). He was expressing a view of Literature as bearing witness to the atrocities of human society. Around the same time, of course, WH Auden, in his eulogy to WB Yeats, appeared to have fewer expectations from Literature:

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making where executives

Would never want to tamper, flows on south

From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs,

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of happening, a mouth.1

But Auden is still talking of Literature’s need to bear witness. This is the ability of the word—trapped on paper— to be murdered and released every time it is read here or there, now and then.

No, the pen is not mightier than the sword. But it is much more slippery. The bravery of words—new, old, new again—is not primarily the bravery of the pen, despite the blood with which many have been stained. It is the braveryof the molten word that assumed flesh, and becomes molten again—changing every time, and changing as flesh too, but never, to plagiarise the religious, losing its soul. It is bravery enabled by the book, and the pen of Literature knows that words in a book are not hard, singular and unchanging as swords. They have a past and they will have a future because of this. Unlike literature, Literature uses words with this knowledge. For the pen might not be mightier than the sword, but the word can be.

1. WH Auden, ‘In Memory of WB Yeats,’ from Selected Poems, edited by Edward Mendelson (Faber and Faber, London, 1979, pp 80-82).